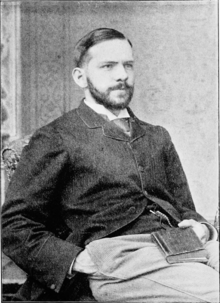

Fred C. Roberts

Frederick Charles Roberts (9 September 1862 – 6 June 1894) was an English physician and medical missionary who served with the London Missionary Society in Mongolia and China. Roberts spent his entire career as a practicing physician in East Asia, dying in China after seven years of mission work. He is best known for his contributions as the sole medical provider and second director at the Tientsin Mission Hospital and Dispensary in China, where he treated an estimated 120-150 patients a day, and for his famine relief efforts in the rural districts outside Tientsin. He also taught at the first Western medical school in China and is the namesake of Roberts Memorial Hospital, which was established in T'sangchou, China in 1903.

Fred C. Roberts | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 9, 1862 Manchester, England |

| Died | June 6, 1894 Tienstin, China |

| Education | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Physician, Missionary |

Early life and education

Fred Roberts was born in Manchester, England in 1862 to parents of distinguished Welsh lineage.[1] He was the youngest of 12 children, although 3 of his siblings passed away before he was born. His parents were devout Christians, and Roberts was exposed to prayer and Bible lessons from a young age. Roberts claimed on his application to the London Missionary Society to have formally become a Christian at the age of 10.[2]

Roberts' early education occurred at a local school run by Christian women.[2] Between the ages of 11 and 13, he attended Manchester Grammar School. He began his college studies at Aberystwyth, the University College of Wales in 1876.[3] It was there that he began pursuing the idea of becoming a missionary in China after he received a letter from his older sister, Mary Roberts, that stated her intentions to go to China as a missionary.[4] He began studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh in 1880 and graduated with his M.B., C.M. in 1886.[1]

Mission work (1887-1894)

In the months following his graduation from medical school, Roberts applied to serve with the London Missionary Society.[2] Upon his acceptance, he was assigned to work with veteran missionary James Gilmour in Mongolia.[3] It was decided that he would be stationed in Tientsin, China for his first months abroad so that he could enhance his Chinese and acclimate to medical missions in China.[2]

Journey

Roberts sailed away from England in September of 1887 on the s.s. Glenshiel. He was accompanied by several veteran missionaries on the ship, and he used his time at sea to study the Bible and Chinese. His ship arrived in Shanghai, China, where he and the other missionaries assigned to Tientsin rested for several days. From Shanghai, Roberts' group traveled north by land to the London Missionary Society settlement in Tientsin.[2]

Tientsin

In Tientsin, Roberts resided with the London Missionary Society medical missionary stationed there, John Kenneth Mackenzie. Working alongside Dr. Mackenzie at the Tientsin Mission Hospital and Dispensary (later Mackenzie Memorial Hospital), he gained experience speaking Chinese, working in a Chinese hospital, and evangelizing with patients and medical students.[5][6] He also taught in the medical school established by Dr. Mackenzie, which was the first medical school in China to teach Western medicine[7]. When Dr. Mackenzie left the mission to treat patients in the countryside for several weeks, Roberts was put in charge of teaching surgery to the Chinese medical students. In March of 1888, Mackenzie decided that Roberts was ready to help Gilmour in Mongolia.[2]

Mongolia

Roberts made the journey to Mongolia with only a servant and a mule-drawn cart.[8] His arrival was highly anticipated by Gilmour, who had no formal medical training. Roberts and Gilmour traveled between the London Missionary Society's three missions in the Mongolian countryside, remaining at each one for a few days. Roberts was involved with both medical work and sharing Christianity among the people. He also set aside time each morning to study Chinese.[2]

Return to Tientsin

A few weeks into his service with Gilmour, Roberts was informed that Dr. Mackenzie had fallen ill and died. Roberts was then asked by the London Missionary Society to return to Tientsin to take over operations of the mission hospital.[8] He was conflicted over leaving Gilmour alone, but he believed it was God's will for him to accept the position. Roberts did not further delay his return to Tientsin, making most of the journey by sea.

Following Mackenzie's death, Viceroy Li withdrew government support of the Tientsin hospital, which led to many of the workers leaving. This left Roberts without qualified assistants, so he did all the medical work in the hospital on his own. Aversion to mattresses and eating while sick, unsanitary conditions in Tientsin, and an initial sentiment of only utilizing foreign doctors as a last resort were other obstacles that Roberts had to contend with in Tientsin.

Roberts incorporated Christianity into the care of all of his patients, suggesting that they pray or give thanks to God. He often lamented that he could not spend more time evangelizing due to his heavy patient load. Seeking to increase missionary work among the local women, he wrote to his sister Mary asking her to join him.[2] She arrived in Tientsin in November of 1888.[3]

By the end of 1888, Roberts had treated over 11,000 patients and 400 outpatients. These numbers increased to 18,000 and 900 in 1890 and continued to increase as his fame spread throughout Northern China. Most of his initial patients were poor, but wealthy patients started coming to his hospital after hearing about his excellent care. Some patients would travel 200 miles to receive care under Dr. Roberts. The hospital was then constantly filled to capacity.

All of Roberts' medical services were free of charge, and he would use his salary from the London Missionary Society to support the hospital's expenses. Cataracts, cholera, and dysentery were the most common conditions he treated.[2] In addition to his treatment and evangelism efforts, Roberts also collected data on dysentery for a thesis he was preparing and was active in the Medical Missionary Association of China.[9]

Dr. G.P. Smith, who Roberts had met at Edinburgh, was appointed to assist him in 1892.[1] Having another doctor in Tientsin allowed Roberts to dedicate more time to the evangelism of the people of Tientsin.[8]

Rural Work and Famine Relief

Following floods in 1890 and 1893, many of the Chinese living in the Northern China countryside lost their homes and sources of food. Roberts recognized that little of the funds distributed by the Chinese Government for relief made it to the suffering people. To help remedy this, he and fellow missionary Rev. Thomas Bryson traveled to affected villages after the floods to provide the people with money to sustain themselves through the cold season.

After the arrival of Dr. Smith in 1892, Roberts and his sister travelled 100 miles southwest to the villages of the Yen Shan district to provide medical care and evangelize among the people. Crowds flocked to Roberts for medical care, and he was constantly invited into people's homes. His days in the countryside typically involved seeing patients all day and then sharing Christianity in the evenings. Roberts treated 1,500 patients and performed 20 operations while in Yen Shan.

Roberts traveled back to Yen Shan with his sister in 1894 on a similar mission.[2]

Death

When Roberts returned from his second Yen-Shan circuit in the spring of 1894, Dr. Smith was recovering from influenza. Roberts sent Smith away from Tientsin so that he could regain his strength before the summer began.[2] In May of 1894, Roberts caught a sudden fever and died a few days later.[3] It is believed he was weakened by the burden of having to manage the hospital on his own.[2]

Legacy

Another medical missionary said of Roberts after his death, "Most careful in his work, he has done twenty-five years' work in seven years: a man of his nature could not go slow." In the absence of Roberts' presence, many of his converts in Tientsin and its rural districts continued to practice Christianity.[2] Mary Roberts carried on her brother's work at the Tientsin hospital until her death in 1933.[3] He was honored posthumously in 1903 when the London Missionary Society named their new hospital in T'sangchou, China after him.[10] Roberts' writing lives on through his contributions to the memoirs of his former colleagues, John Kenneth Mackenzie, Medical Missionary to China and The Story of James Gilmour.[5][2]

References

- Mardy Rees, Thomas (1908). Notable Welshmen (1700-1900). Carnarvon: Herald Office. p. 436.

- Bryson, Mary (1895). Fred. C. Roberts of Tientsin. London: H.R. Allenson. ISBN 9781298759573.

- Jenkins, Robert (1959). "ROBERTS family, of Mynydd-y-gof, Bodedern, Anglesey". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- "Ladies' Meeting". The Chronicle of the London Missionary Society. John Snow & Company: 129. June 1896.

- Bryson, Mary (1889). John Kenneth MacKenzie; Medical Missionary to China. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 376. ISBN 9781355831297.

- "Mackenzie Memorial Hospital, 79 Rue de Taksu; Tientsin Mission Hospital And Dispensary | Western Medicine in China, 1800-1950". ulib.iupui.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-02.

- Western medicine : an illustrated history. Loudon, Irvine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 978-0-19-159176-1. OCLC 45729050.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Lovett, Richard (1899). The History of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895. London Missionary Society.

- "Correspondence". The China Medical Missionary Journal. Kelly & Walsh. 4: 85. Winter 1890.

- "Roberts Memorial Hospital Photographs - Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 2019-10-27.