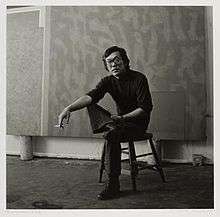

Frank Okada

Frank Okada (1931 - 2000) was an American Abstract Expressionist painter, mainly active in the Pacific Northwest. His mature style often featured brightly colored, off-kilter geometric shapes done in large format, including round canvasses; subtly elaborate brushwork suggested the influence of both traditional Asian art and the "mystics" of the Northwest School. His later work at times used symbolic shapes which more directly evoked his Nisei heritage and the years he spent in detention camps with his family during World War II.

He taught art at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon from 1969 to 1999.

Early life

Frank Sumio Okada was born in Seattle, Washington in 1931.[1] His parents, immigrants from the Hiroshima area in Japan, managed residence hotels in the International District near downtown Seattle. He was the youngest of four brothers, and had two younger sisters.[2] In 1942, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Okada and his family spent two years in detention at Camp Harmony and the Minidoka Relocation Center, and another year in Ione, Washington (outside the Japanese exclusion zone), where his father worked in a laundry. His brothers Charlie and John served in the US Army. Charlie Okada was in the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, along with an older foster brother who was killed in action in Italy.[2] John Okada later authored the acclaimed novel No-No Boy.

Returning to Seattle after the war, Frank Okada attended Garfield High School and began taking painting lessons on Saturdays at the Leon Derbyshire School of Fine Art. He also began a lifelong infatuation with jazz music, haunting the record stores and live venues of Seattle's Jackson Street, which was two blocks from the Pacific Hotel, where he lived with his family. Among his schoolmates were future jazz legends Quincy Jones and Buddy Catlett.[1] After graduating from high school he studied commercial art at Edison Technical School, then went to Cornish College of the Arts in Seattle.[2]

Career

Okada was drafted and did a two-year stint in the US Army, including several months at an evacuation hospital in South Korea during the Korean War. He then attended the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan, receiving a BFA degree in 1957.[3] While at Cranbrook he began visiting New York City, where he met many of the leading lights of Abstract Expressionism, whose inspiration began to show in his own work. After winning a Whitney Fellowship in 1957 he spent about a year in New York, studying and exhibiting. Evenings were often spent at the Cedar Tavern, interacting with the members of the city's burgeoning modern art scene. Okada's work received considerable attention. He was associated with the Brata Gallery, where he showed regularly, and was profiled in a 'new talent' issue of Art in America magazine. However, he found it difficult to develop his style amid the excitement of New York, and was disappointed by how quickly commercial interests and new hierarchies took root as the city became the world's new focus of modern art. In 1958 he returned to Seattle.[1]

Over the next several years Okada spent long periods in Kyoto and Paris, funded by Fulbright and Guggenheim Fellowships, interspersed with periods of working as a commercial artist for the Boeing company in Seattle.[4] He shared a studio space with friend and fellow painter William Ivey in the rough-hewn Pioneer Square section of downtown Seattle. In 1968 the two briefly opened the Seattle Studio School, giving private lessons to a handful of students. He continued his friendship with painter/collagist Paul Horiuchi, whom he had first met in the mid-1950s when Horiuchi was still working as an auto body repairman ("The first part of Paul I saw were his feet, as he was working under a car," Okada later recalled),[1] and he had long discussions about Zen Buddhism and its relationship to art with Mark Tobey and Tomatsu Takizaki, an antique merchant, poet, and Zen practitioner he'd met through Horiuchi.[2]

By the late 1960s Okada's painting style had coalesced into a unique abstract style which subtly reflected the growing awareness of ethnic identity of the era. His work became increasingly popular, with solo exhibitions in the Northwest and group shows in the US, France, and Japan. In 1969 he became one of the artist's represented by Seattle's Richard White Gallery; the same year he was offered, and accepted, a teaching position at the University of Oregon in Eugene, which he held for the next thirty years.[1] Throughout his tenure there he continued to paint and exhibit, establishing himself as a major figure in Asian-American and Pacific Northwestern art, and a well-known name in modern art internationally.

In 1976 Okada married Frances Sharon Fling in Eugene.[2]

Shortly after retiring from the University, Okada underwent surgery for cancer. He died at Sacred Heart Hospital in Eugene on Oct. 30th, 2000, at age 69.[5]

Said painter Fred Mitchell, who had instructed Okada at Cranbrook Academy: "[He] was the most consistently expressive painter, bringing together great power for shaping and giving life to color forms. To look at his paintings was to fall into the grip of his formative intensity, and to feel the full force of his form-creating energy."[1]

Legacy

Okada was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1967, a Fulbright Fellowship in 1959 and a Whitney Fellowship in 1957. He had several solo exhibitions at regional institutions, including the Whatcom County Museum of Art, Bellingham, WA (1997), Portland Art Museum, Oregon (1972), and Tacoma Art Museum, Washington (1970). Okada’s work has also been shown in group exhibitions such as Asian Tradition, Modern Expression, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Museum, Rutgers University, NJ (1997); Light, Shadow and Gesture: By Northwest Artists, Seattle Art Museum (1997); Washington: 100 Years, 100 Paintings, Bellevue Arts Museum, Bellevue, WA (1995); ART/LA 90, Los Angeles, CA (1991) and Japan and the Northwest, the National Museum of Art, Osaka, Japan (1982). He was represented by the Laura Russo Gallery in Portland, and the Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle.

Works by Okada are included in the collections of the Philbrook Museum, the Museum of Northwestern Art in La Conner, WA, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA; the Portland Art Museum; SAFECO Insurance Company, Seattle; the Seattle Art Museum; Swedish Medical Center, Seattle; the Tacoma Art Museum, WA; the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, in Eugene, OR; the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, WA; and many others.[6]

References

- Frank Okada: The Shape of Elegance, by Kazuko Nakane and Lawrence Fong; University of Washington Press, 2005; ISBN 0295985666

- Oral history interview with Frank S. Okada, 1990 Aug. 16-17, by Barbara Johns; Smithsonian Archives of Art; http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-frank-s-okada-11693 retvd 7 10 14

- John Okada biography, University of Washington faculty; http://faculty.washington.edu/kendo/okada.html retvd 7 10 14

- Encyclopedia of Asian American Artists, by Kara Kelley Hallmark; Greenwood, 2007; ISBN 031333451X

- "Noted artist Frank Okada, 69, dies", by Sheila Farr, The Seattle Times, Nov. 2, 2000

- Greg Kucera Gallery, Inc., biography of Frank Okada. http://www.gregkucera.com/okada.htm retvd 7 10 14