Francesco Botticini

Francesco di Giovanni Botticini (1446 – 16 January 1498[1]), commonly referred to as Francesco Botticini, was an Italian Early Renaissance painter, normally of religious subjects on panel. He was born in Florence and remained active as a painter until his death in 1498. He studied in the workshops of Neri di Becci, Cosimo Rosselli and Andrea del Verrocchio. He established his own Florentine workshop after a brief period as Neri di Bicci's assistant. Although there are few works attributed to Botticini directly, in recent years historians have unearthed of a considerable number of works that were certainly authored by Botticini. Since the assembly of the complete record of his works, he is viewed as a remarkable minor master of Renaissance Art.[2]

Botticini's best known works are the Tabernacle of the Sacrament, Assumption of the Virgin and Madonna Child in Glory with Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Bernard.[3]

Life

Francesco Botticini was born in 1446 in Florence, although the exact date is unknown. His father, Giovanni di Domenico di Piero, was also a painter. Giovanni's connections in the art world at that time led to the opportunity for Francesco to become a paid assistant to Neri di Bicci. He began as an assistant in the prosperous workshop on 22 July 1459 under a contract of one year of training. At this time Francesco was 13 years of age. The group of highly talented artists in the workshop led to important exposure for the young Botticini.[2][4]

Despite the one-year contract, Francesco left Bicci's workshop in July 1460 after only nine months of training. Scholars account for his early independence by pointing to the influence of his father's painting career and connections to other artists. When he left Bicci's workshop, it is believed that he spent considerable time in the workshop of Andrea del Verrocchio, alongside many of his famous contemporaries, including Leonardo da Vinci, Lorenzo di Credi, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Pietro Perugino. However, there is no documentary evidence that he worked in the workshop of Verrocchio. Direct evidence of their relationship during this time is found in Francesco's collaboration with Verrocchio on works, and the influence of Verrocchio's style on Francesco's paintings. Likely due to the competition of other talented artists present in the workshop, in 1469 Botticini opened up his own workshop, as reported in an arbitration document of the year. However, his working relationship with Verrocchio continued until at least 1475.[5][2][4]

Francesco remained close with his father Giovanni di Domenico, who oversaw his working contracts until 1475. In 1475, Francesco filed for emancipation from paternal authority, which was granted in 1477 according to legal records.[5]

On 16 January 1498, Francesco Botticini died in Florence, Italy at the age of 51. At the time he was in the process of working on the monumental Tabernacle of the Sacrament for the collegiate church of Empoli. His son, Raffaello Botticini, was commissioned to finish the altarpiece after his death.[2]

Works

Tabernacle of the Sacrament

The Tabernacle of the Sacrament was commissioned as an altarpiece for the high altar of the church in Empoli, Italy. This remains as one of Botticini's most notable works. Saint Andrew is pictured on the left of the ciborium. Saint Andrew was the patron saint of the church at the time. On the right of the ciborium, the home of the Eucharist, is a painting of Saint John the Baptist. Below the two main pictures are three smaller paintings in the predella. On the left the Martyrdom of St. Andrew is depicted, directly below the painting of the Saint. In the center the Last Supper is found, with the martyrdom of Saint John the Baptist in the compartment to the right, below the larger painting of Saint John the Baptist. The paintings are enclosed in a wooden frame which has been carved and gilded.[6][2]

The altarpiece was set to be completed by 15 August 1486, however it was not actually installed in the church until 1491. The work was not complete until 1504 when the church commissioned Francesco Botticini's son, Raffaello, to complete the work in accordance with the original contract.[6][2]

Assumption of the Virgin with Saints and the Angelic Hierarchies

The Assumption of the Virgin is Francesco Botticini's most famous work. It was first attributed to Sandro Botticelli in Vasari's The Lives of the Artists but has since then been confirmed to be Botticini's work by art historians. Botticini began working on the painting in early 1475, and completed it two years later in 1477. The piece was commissioned by the poet Matteo Palmieri and his wife Niccolosa de'Serragli. It hung in the church of S. Pier Maggiore in Florence, where Palmieri was buried, although records indicate this was not the original destination for the work. The painting can now be found in the National Gallery, London. The painting has almost the same dimensions of the Last Judgment by Hans Memling.[7][5]

The subject of the painting was greatly influenced by the patrons, who are depicted kneeling on either side of the Assumption. Niccolosa de'Serragli is pictured dressed as a nun, despite never being a nun during her lifetime. This may be explained through her active role in the decision making of the painting after the death of her husband. The background of the painting also connects directly to the patrons as it includes views of Florence. The inclusion suggests that Florence is the audience for this holy event. One of Palmieri's properties on the Fiesole is also included. The white farm in the landscape is meant to resemble the farm included in Serrageli's dowry.[7][5][8]

The painting's subject closely resembles the last stanza of Palmeri's Città di Vita poem which discusses the reception of the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven. The painting illustrates a clear separation between heaven and earth. Scholars believe that Botticini was forced to exaggerate the division in order to comply with the poet's wishes. In heaven, nine tiers of angels and saints intermingle. Martin Davies believes that the intermingling represented the changing of angels back to saints when they refused to take sides over the fall of Lucifer.[7][5]

This created much speculation over the possibility of the painting being heretical, however these views have been disproved. If the painting had been heretical the church of San Pier Maggiore would not have allowed it to continue to stay on view.[7]

Madonna and Child in Glory with Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Bernard

Madonna and Child in Glory with Saint Mary Magdalen and Saint Bernard is a painting by Botticini most likely intended for a high altar. This is one of the best examples of Botticini's advanced period of artistry, clearly showing the influence of his contemporaries and masters. The date of completion has been recorded as 1485 based on the style of the work. It is proven that the painting was originally intended for the San Freidiano church in Cestello, due to the parallel's between the saints in the painting and the patron saints of the church. Vasari previously attributed the piece to Cosimo Rosselli, however has now been rightfully attributed to Botticini.[9][10]

This work is memorable for its unusual depiction of saints. The four saints in the picture, from left to right, are Benedict, Francis, Sylvester, and Anthony Abbot. All four saints carry closed books, which is an unusual occurrence. While Anthony Abbot and Saint Sylvester commonly carry a book in their depiction, Francis rarely holds a book. It is also unusual to see Benedict with a book, as scholarship is not something for which he was known. Benedict is also clothed in a black robe, rather than his typical white robe. In addition, none of the saints look towards the Madonna and Child in the center of the frame, instead they all look in different directions.[9][10]

This altarpiece includes a remarkable use of symbolic animals and plants. The curtains framing the work are trimmed with ermine fur, which is clear through the inclusion of the black tips on the white fur. The ermine is often used in religious art as a symbol of purity and chasity, as seen in Leonardo da Vinci's Lady with the ermine. The ermine (also known as a weasel) has been connected to the conception of Christ.[9]

Botticini also includes an interesting design in the throne of the Virgin Mary, centered around a scallop-like dome. The scallop shell is symbolic of religious pilgrimage.[9]

The earth below the Madonna and Child and the Saints has an abundant amount of various animals and plants. These include a dragon, which is a symbol of Satan. The evil characteristic of the dragon is highlighted in the inclusion of bloodshot eyes. The dragon is usually included as a reference to Saint Sylvester. Similarly, the pig in the bottom right is a common symbol of Saint Anthony Abbot, representing gluttony.[9]

A highly debated animal is the white dove which is depicted drinking from a steam in the very bottom of the painting. The dove is usually used to represent the Holy Spirit, however the style of this dove does not resemble any of the usual marks of the Holy Spirit. Herbert Friedmann has theorized that the dove is instead a symbol of the twin sister of Saint Benedict, Saint Scholastica. Saint Scholastica was the head of all the Benedictine nuns. Although it is unusual to depict a saint in this way, it is said that Saint Scholastica's soul departed to heaven in the form of a white dove when her twin brother died. This is supported by its noticeable lack of any symbols of the Holy Spirit, and its close proximity to Saint Benedict in the frame.[9]

Other symbolic animals include the goldfinch, which represents richness. A lizard is included to represent the "sun lizard" from the lend of Physiologus. In line with the legend, the sun lizard is the only member of the painting that looks at the baby Jesus. Lastly, a tortoise is included, which is an uncommon religious symbol. The tortoise represents reticence and chastity.[9]

This altarpiece by Botticini is unique in its remarkable inclusion of plants and animals, unlike any other Florentine painting of its period. The piece is often described as the most artistically profound work that Botticini produced during his life.

The painting is now located at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, New York.[11]

San Gerolamo

Around the year 1490, Botticini completed an altarpiece of Saint Jerome, which is now housed in the National Gallery in London, England. The Saint is depicted in the center panel of the altarpiece, clothed in traditional repentance attire. Surrounding the Saint are other figures including Pope Damasus, Saint Eusebius, Saint Paula, Saint Eustochium, angels above and kneeling donors below. Although St. Jerome is framed in a sub-panel in the center, the entire altarpiece works together as a realistic single scene. Art Historian Charles Darwent describes the scene in his Article for The Independent on Sunday, "By giving his picture-within-a-picture of St Jerome its own gilt farm, the artist (Botticini) sets up a sequence of overlapping realities. The framed image exists as a separate artwork for us, the viewer, but also for the painted saints who seem to study it: even holy martyrs, it says, can be moved by the power of art" Botticini combines three different realities within one altarpiece: the reality of St. Jerome, the Saints studying him and another reality of the kneeling donors.[12]

The Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John The Baptist in a Landscape

In the latter part of his art career, Botticini was praised for his private devotional paintings. This painting's subject, Madonna and Child, was one that he often painted and experimented with. Since 1900, art scholars have conclusively agreed that Botticini is the author of this particular tondo. This painting is very similar in style to the Cassa di Risparmio in Florence, although this painting includes a depiction of St. John the Baptist as an infant. Botticini includes his signature landscape in the background, complete with an ambiguous walled city and decorative plants and flowers. The painting has remained in remarkable condition in part due to its completion on just a single panel. The condition allows for a close inspection of the details of the Madonna. The robe, facial features and golden hair have been linked by scholars to Verrocchio and Botticelli.[13]

The painting was a part of Sotheby's 2013 Old Masters and British Paintings Evening Sale, and sold for $494,500.[13]

Drawings

Unlike many of Botticini's Renaissance contemporaries, there remain very few drawings attributed to the artist himself. Bernard Berenson has found eight different drawings that seem to certaintly be Botticini's work. Berenson discusses these in separate editions of Drawings of the Florentine Painters. Of these eight drawings only three have been directly connected to paintings of Botticini's.[14]

One of the three drawings connected to Botticini's paintings has since been attributed to Domenico Ghirlandaio as he completed a study for a fresco ascribed to Bastiano Mainardi. It was originally believed to be a study for Botticini's St. Jerome figure in St. Jerome in Penitence with Saints and Donors, but is now considered close to Ghirlandaio's work and style.[14] The other two drawings that have been directly linked to a painting of Botticini's are considered studies for the figures in his Assumption of the Virgin with Saints and the Angelic Hierarchies, which is now in the London National Gallery. Both drawings are now in the National Museum, Stockholm. However, in Giorgio Vasari's writings these drawings have instead been attributed to Sandro Botticelli, forcing scholars to doubt the connection to Botticini.[14]

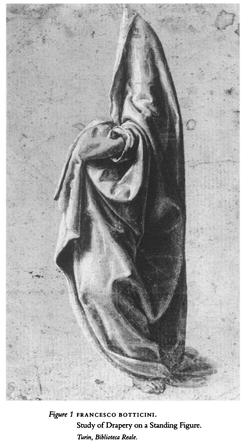

Following these discoveries William Griswold has discovered numerous other works that add to Botticini's small drawing portfolio. These include a drawing of a Turin, and its similarities to the figure of St. Andrew in Botticini's Tabernacle painting. The similarities in the drawing and the painting include the positions of the hand and foot of both figures, as well as the way the drapery falls and folds. Scholars believe that Botticini used the technique of dipping the drapery into wet plaster in order to create a realistic model to study from. The details of each Turin are almost identical, and the slight differences that are present support the conclusion that the painting was not a direct copy of the drawing, rather that the drawing was a study for the Tabernacle.[6]

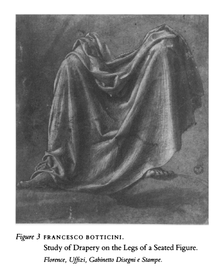

After the connection to the Botticini from the Turin was made, the art historian Dalli Regoli noticed the likeliness of the style to another drawing study, Study of Drapery on the Legs of a Seated Figure which resides in the Uffizi in Florence, Italy. Although the study of the drapery was previously attributed to Piero di Cosimo, William Griswold has suggested an alternative viewpoint. He believes that the similarities between the drapery drawing and the Turin drawing indicate that they were both completed by Francesco Botticini. He supports this claim with the drapery drawings connection to the drapery of Christ in his Assumption altarpiece.[6]

Griswold believes that both drawing studies used the technique of dipping drapery into wet plaster to allow for easy manipulation of the material at the hand of the artist. However, there are differences between the two drawings. The Turin drawing was made only using a brush, while the Florence drawing was made with both pen and brown ink, completed on orange tinted paper, linking it to sketches for the Palmieri Assumption altarpiece. For these sketches Botticini chose to use a combination of scratchy pen marks and zigzag hatching to complete the structure of the model. Griswold infers from the similarity of the four separate drawings that Botticini must have been the artist of all four.[6]

Another drawing credited to Botticini has been linked to his San Gerolamo altarpiece, discussed above. The center panel depicts a kneeling St. Jerome, for which he completed a drawing as a study for the figure. Once again, the actual painting of St. Jerome did not exactly copy this drawing. Instead, similarly to other drawings done by Botticini, the drawing was used as an early study from which many changes were made. Art Historian Bernhard Degenhart concludes that although there are differences between the study and the final product, the works are both absolutely Botticini's. He attributes many of the differences to the different mediums used. Their similarities include the folds in their drapery, the shadowing, the spread of the material across the grown, and the heightening of white within the clothing. The placement of the hand at the breastbone is also convincingly similar.[15][12]

Inventory of known works

Bernard Berenson compiled a complete list of Francesco Botticini's known works for his Florentine School periodical in 1963.[16]

Legacy

Francesco Botticini is not often included in the conversation of the masters of Renaissance art. However, his significant contribution to art in the 15th century formed a legacy that affected art in his time and in the contemporary world.

Charles Darwent discusses Botticini's legacy in his article about the artist's painting San Gerolamo. The altarpiece, which was one unified scene created with a combination of multiple panels, is described as an engineering masterpiece as well as an art masterpiece. The uncommon painted outer frame gave Botticini the chance to experiment with his artistry and stray from the strict guidelines of the patron. This trend became popular with other artists in Botticini's realm of influence. Before this style of experimentation with the flexibility of the panels, artists were slaves to the carpenters initial construction of the altarpiece. Darwent believes that Botticini's new style of constructing interchangeable panels allowed artists to stray from the orthodox style of the patron and employed carpenter of the piece.[12]

Botticini also influenced the modern art world with his painting of Saint Sebastian, a Christian martyr who was killed with arrows because of his faith. In his painting Botticini depicts the Saint bound to a wooden pole, with arrows piercing his torso. In April 1968, Esquire Magazine imitated Botticini's painting in their cover shot of their article on Muhammad Ali, The Passion of Muhammed Ali. The cover was meant to relate the persecution of Saint Sebastian to the persecution of Muhammad Ali when we was stripped of his heavyweight boxing title for refusing to serve in the Vietnam War. George Lois, the art director of the magazine at the time, came up with the idea for the cover and pitched it to Ali. Ali initially liked the connection between the suffering of the Saint and himself, but initially refused to pose as a Christian. Eventually he agreed after speaking with the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, and studying a postcard of Botticini's painting for inspiration. The final product shows Ali with his hands bound behind him, arrows piercing his torso, his head tilted upwards in pain, imitating the Saint Sebastian that Botticini created.[17][18]

Notes

- Getty Museum entry.

- Rizzo, Anna Padoa (26 May 2010). "Botticini, Francesco". Oxford Art Online.

- "Francesco Botticini". The National Gallery. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Serros, Richard David (1999). THE VERROCCHIO WORKSHOP: Techniques, production and Influences. University of Louisville. pp. 221–226.

- Bagemihl, Rolf (May 1996). "Francesco Botticini's Palmieri Altar-Piece". Burlington Magazine Publications LTD. 138 (1118): 308–314. JSTOR 886902.

- Griswold, William (Summer 1994). "Drawings by Francesco Botticini". Master Drawings. 32: 151–154.

- King, Catherine (1987). "The Dowry Frams of Niccolosa Sserragli and the Altarpiece of the Assumption in the National Gallery London (1126) Ascribed to Francesco Botticini". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte. 50 (2): 275–278. doi:10.2307/1482328. JSTOR 1482328.

- Branagan, David (2006). "Geology and the artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth century, mainly Florentine". Geology Society of America. 411: 31–35.

- Friedmann, Herbert (Summer 1969). "Footnotes to the Painted Page: Iconography of an Altarpiece by Botticini". The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin. 28 (1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/3258469. JSTOR 3258469.

- Alison, Luchs (1976). Cestello: A Cistercian Church of the Florentine Renaissance. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Johns Hopkins University. pp. 77–79.

- "Met Audio Guide Online". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Darwent, Charles (July 2011). "All Things Bright and Beautiful". The Independent on Sunday. London, United Kingdom: 6.

- "Francesco Botticini". Sotheby's. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- Berenson, Bernard. "Francesco Botticini". Drawings of the Florentine Painters.

- Degenhart, Bernhard (December 1930). "Francesco Botticini, Study of a St. Jerome". Old Master Drawings: 49–51.

- Van Marle, Raimond (1938). The Development of Italian Schools of Painting. XIX. The Netherlands: The Hague. pp. 39–41.

- "How Muhammad Ali's 'Esquire' Cover Helped Cement a Legend". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- "This Way In". Esquire. 2008. ProQuest 210369046.

References

- A. Padoa Rizzo. "Botticini, Francesco." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 21 February 2017

- Bagemihl, Rolf. "Francesco Botticini's Palmieri Altar-Piece." The Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1118 (1996): 308-14.

- R. van Marle: The Development of Italian Schools of Painting, 19 vols (The Hague, 1931, 2/1970), xiii, pp. 390–427

- M. Davies: The Earlier Italian Schools, London, N.G. cat. (London, 1951, 2/1961), pp. 118–27

- B. Berenson: Florentine School (1963), p. 39

- E. Fahy: ‘Some Early Italian Pictures in the Gambier Parry Collection’, Burl. Mag., cix (1967), pp. 128–39

- B. Berenson: The Drawings of Florentine Painters, 2 vols (Chicago, 1938, rev. 2/1969), i, p. 70; ii, p. 61

- H. Friedman: Iconography of an Altarpiece by Botticini, Bull. Met., xxviii (1969), pp. 1–17

- F. Zeri and E. Gardner: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Italian Paintings: Florentine School (New York, 1971), pp. 125–7

- W. M. Griswold: ‘Drawings by Francesco Botticini’, Master Drgs, xxxii/2 (Summer 1994), pp. 151–4

- P. L. Rubin: Art and the imagery of memory, Art, memory, and family in Renaissance Florence, ed. G. Ciappelli and P. L. Rubin (Cambridge, 2000), pp. 67–85

- King, Catherine. "The Dowry Farms of Niccolosa Serragli and the Altarpiece of the Assumption in the National Gallery London (1126) Ascribed to Francesco Botticini." Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 50, no. 2 (1987): 275-78.

- Shaw, J. B. (1935). Francesco Botticini. Old Master Drawings, 9, 58. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1293741301

- Degenhart, B. (1931). Francesco Botticini. Old Master Drawings, 5, 49. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1293863529

Further reading (in Italian)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Francesco Botticini. |

- A. Padoa Rizzo: ‘Per Francesco Botticini’, Ant. Viva, xv/5 (1976), pp. 3–19 (Italian)

- L. Venturini: Francesco Botticini (Florence, 1994) (Italian)

- R. Roani Villani: ‘Relazione sulle pitture: Contributo alla conoscienza del patrimonio artistico della diocesi di S Miniato’, Erba d’Arno, xxxii–xxxiii (1988), pp. 62–94 (Italian)

- A. Garzelli: La miniatura fiorentina del quattrocento, 2 vols (Florence, 1985), i, pp. 95–7 (Italian)

- Neri di Bicci: Le ricordanze, 1453–1475, ed. B. Santi (Pisa, 1976), pp. 126–7, 333 (Italian)

- G. Poggi: ‘Della tavola di Francesco di Giovanni Botticini per la Compagnia di Sant’Andrea di Empoli’, Rivista d’arte, iii (1905), pp. 258–64 (Italian)

- P. Bacci: ‘Una tavola sconosciuta con San Sebastiano di Francesco di Giovanni Botticini’, Boll. A., n.s. iv(1924–25), pp. 337–50 (Italian)

- Arte in Valdelsa (exh. cat., ed. P. dal Poggetto; Certaldo, Pal. Pretorio, 1963), p. 60 (Italian)

- L. Bellosi: ‘Intorno ad Andrea del Castagno’, Paragone, xviii/211 (1967), pp. 10–15 (Italian)

- A. Garzelli: Il ricamo nell’attività artistica di Pollaiuolo, Botticelli e Bartolomeo di Giovanni (Florence, 1973), pp. 20–22 (Italian)

- A. Garzelli: La miniatura fiorentina del quattrocento, 2 vols (Florence, 1985), i, pp. 95–7 (Italian)

- A. Padoa Rizzo: ‘Pittori e miniatori nella Firenze del quattrocento: In margine a un libro recente’, Ant. Viva, xxv/5–6 (1986), pp. 5–15 (Italian)

- R. Roani Villani: ‘Relazione sulle pitture: Contributo alla conoscienza del patrimonio artistico della diocesi di S Miniato’, Erba d’Arno, xxxii–xxxiii (1988), pp. 62–94 (Italian)