Foundations of the Science of Knowledge

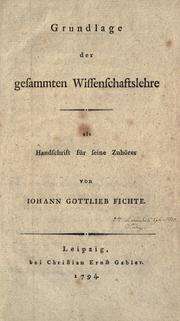

Foundations of the Science of Knowledge (German: Grundlage der gesammten Wissenschaftslehre) is a 1794/1795 book by the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte. Based on lectures Fichte had delivered as a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Jena, it was later reworked in various versions. The standard Wissenschaftslehre was published in 1804, but other versions appeared posthumously.[1]

| |

| Author | Johann Gottlieb Fichte |

|---|---|

| Original title | Grundlage der gesammtena Wissenschaftslehre |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | German |

| Subject | Epistemology |

Publication date | 1794/1795 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 324 (1982 Cambridge University Press edition) |

| ISBN | 978-0521270502 |

| a gesamten in modern German. | |

Ideas

Science of Knowledge has first established Fichte's independent philosophy.[2] The contents of the book, which were divided into eleven section, were crucial in the way the thinker has grounded philosophy as - for the first time - a part of epistemology.[3] In the book, Fichte has also claimed that an "experiencer" must be tacitly aware that he is experiencing in order to lead to "noticing".[4] This articulated his view that an individual's experience is essentially the experiencing of the act of experiencing so that his so-called "Absolutely Unconditioned Principle" of all experience is that "the I posits itself".[4]

Reception

In 1798, the German romantic Friedrich Schlegel identified the Wissenschaftslehre, together with the French revolution and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Wilhelm Meister, as "the most important trend-setting events (Tendenzen) of the age."[5]

Michael Inwood believes that the work is close in spirit to the early works of Edmund Husserl, including the Ideas (1913) and the Cartesian Meditations (1931).[6]

The Wissenschaftslehre has been described by Roger Scruton as being both "immensely difficult" and "rough-hewn and uncouth".[1]

See also

References

Notes

- Scruton 2000. p. 208.

- Zack, Naomi (2009-09-01). The Handy Philosophy Answer Book. Canton, MI: Visible Ink Press. pp. 224. ISBN 9781578592265.

- Henrich, Dieter (2003). Between Kant and Hegel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 208. ISBN 0674007735.

- Gottlieb, Gabriel (2016). Fichte's Foundations of Natural Right. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 141. ISBN 9781107078147.

- Seidel 1993. p. 1.

- Inwood 2005. p. 410.

Bibliography

- Inwood, M. J. (2005). Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926479-1.

- Scruton, Roger (2000). Kenny, Anthony (ed.). The Oxford History of Western Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-289329-7.

- Seidel, George J. (1993). Fichte's Wissenschaftslehre of 1794. A Commentary on Part 1. Purdue University Research Foundation: Purdue University Press. ISBN 1-55753-017-3.