Floods in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is a land of rivers. It is prone to flooding due to being situated on the Brahmaputra River Delta (also known as the Ganges Delta) and the many distributaries flowing into the Bay of Bengal. Due to being part of such a basin and being less than 5 metres above mean sea level, Bangladesh faces the cumulative effects of floods due to water flashing from nearby hills, the accumulation of the inflow of water from upstream catchments, and locally heavy rainfall enhanced by drainage congestion. Bangladesh faces this problem almost every year. Coastal flooding, combined with the bursting of river banks is common, and severely affects the landscape and society of Bangladesh. 80% of Bangladesh is [floodplain],[1] and it has an extensive sea coastline,[2] rendering the nation very much at risk of periodic widespread damage. Whilst more permanent defenses, strengthened with reinforced concrete, are being built, many embankments are composed purely of soil and turf and made by local farmers. Flooding normally occurs during the monsoon season from June to September. The convectional rainfall of the monsoon is added to by relief rainfall caused by the Himalayas. Meltwater from the Himalayas is also a significant input.

_March%2C_(b)_April%2C_(c)_June%2C_and_(d)_August_2017.jpg)

Each year in Bangladesh about 26,000 square kilometres (10,000 sq mi) (around 18% of the country) is flooded, killing over 5,000 people and destroying more than seven million homes. During severe floods the affected area may exceed 75% of the country, as was seen in 1998. This volume is 95% of the total annual inflow. By comparison, only about 187 trillion l (1.87×1011 m3; 6.6×1012 cu ft) of streamflow is generated by rainfall inside the country during the same period. The floods have caused devastation in Bangladesh throughout history, especially in 1966, 1987, 1988 and 1998. The 2007 South Asian floods also affected a large portion of Bangladesh.

Benefits of flooding

Small scale flooding in Bangladesh is required to sustain the agricultural industry, as sediment deposited by floodwaters fertilises fields. The water is required to grow rice, so natural flooding replaces artificial irrigation, which is time consuming and costly to build. Salt deposited on fields from high rates of evaporation is removed during floods, preventing the land from becoming infertile. The benefits of flooding are clear in El Niño years when the monsoon is interrupted. As El Niño becomes increasingly frequent, and flood events appear to become more extreme, the previously reliable monsoon may be succeeded by years of drought or devastating floods.

Types of floods

While the issue of flooding and the ongoing efforts to limit its damages are prevalent throughout the entire country, several types of floods have recently occurred regularly, affecting different areas in their own distinct way. These flood types include:[4]

- flash floods in hilly areas

- monsoon floods during monsoon season

- normal bank floods from the major rivers, Brahmaputra, Ganges and Meghna

- rain-fed floods

Historic floods

The country has a long history of destructive flooding that has had very adverse impacts on lives and property. In the 19th century, six major floods were recorded: 1842, 1858, 1871, 1875, 1885 and 1892. Eighteen major floods occurred in the 20th century. Those of 1987, 1988 and 1951 were of catastrophic consequence. More recent floods include 2004 and 2010.

The catastrophic floods of 1987 occurred throughout July and August[5] and affected 57,300 square kilometres (22,100 sq mi) of land, (about 40% of the total area of the country) and was estimated as a once in 30-70 year event. The seriously affected regions were on the western side of the Brahmaputra, the area below the confluence of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra and considerable areas north of Khulna.

The flood of 1988, which was also of catastrophic consequence, occurred throughout August and September. The waters inundated about 82,000 square kilometres (32,000 sq mi) of land, (about 60% of the area) and its return period was estimated at 50–100 years. Rainfall together with synchronisation of very high flows of the three major rivers of the country in only three days aggravated the flood. Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, was severely affected. The flood lasted 15 to 20 days.

In 1998, over 75% of the total area of the country was flooded, including half of Dhaka.[6] It was similar to the catastrophic flood of 1988, in terms of the extent of the flooding. A combination of heavy rainfall within and outside the country and synchronisation of peak flows of the major rivers contributed to the flood. 30 million people were made homeless and the death toll reached over a thousand.[6] The flooding caused contamination of crops and animals and unclean water resulted in cholera and typhoid outbreaks. Few hospitals were functional because of damage from the flooding, and those that were open had too many patients, resulting in everyday injuries becoming fatal due to lack of treatment. 700,000 hectares of crops were destroyed,[7] 400 factories were forced to close, and there was a 20% decrease in economic production. Communication within the country also became difficult.

The 1999 floods,[8] although not as serious as the 1998 floods, were still very dangerous and costly. The floods occurred between July and September, causing many deaths, and leaving many people homeless. The extensive damage had to be paid for with foreign assistance. The entire flood lasted approximately 65 days.

The 2004 flood was very similar to the 1988 and 1998 floods with two thirds of the country under water.

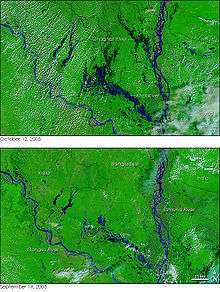

In early October 2005, dozens of villages were inundated when rain caused the rivers of northwestern Bangladesh to burst their banks.

Floods also occurred in 2015 and 2017.

Details of the 2017 flood(s) in Bangladesh

_April_and_June%2C_(b)_June_and_August.jpg)

In 2017, unpredicted early heavy rain caused flooding in several parts of Bangladesh and damaged pre-harvested crops in April. The April flood continued until the last week of August and caused substantial damage to housing, property, and infrastructure. Using Sentinel-1, comprehensive flood inundation maps of Bangladesh for March, April, June, and August 2017 show that the presence of perennial waterbodies in March 2017 covering an area of 5.03% in Bangladesh. In April, a total flood-inundated area was 2.01%, most inundation occurring in cropland (1.51%), followed by rural settlement and homestead orchard areas (0.21%) and other areas (0.29%). Similarly, more area was inundated during the catastrophic June and August months, with inundation covering 4.53% and 7.01%, respectively.[3]

Climate variability

.jpg)

From March to September in a typical year, the citizens of Bangladesh are the most susceptible to major flooding, as a mixture of the monsoon seasons and the rising of major rivers and their tributaries reach their peak as the snow starts to melt and the rain starts to pour.[4]

the rivers flow from India into Bangladesh also sometimes the Himalayas.

Widespread flooding in Bangladesh, as seen in 1988, 1998 and 1991 has caused widespread destruction in one of the least developed countries in the world. With three of the world's mightiest river systems and being situated in the world's largest delta, riverbank erosion is taking away precious land from the small nation with a growing population every year. The economic development of the rural sphere is largely intertwined, as every year the populace loses property and livelihood. South Asian people, 70 percent of whom lives in rural areas also account for 75 percent of the poor, most of whom rely on agriculture for their livelihood. Each year they are disproportionately affected by the effects of climate change. Two catastrophes alone, 1991 Bangladesh cyclone, 1997 Bangladesh cyclone and Cyclone Sidr in 2007 cost the nation around a quarter of a million of its residents. There needs to be serious considerations to mitigate the effects of climate change and invest in capacity building of each system component to secure the future of this country.

This global change is likely to have a more dramatic effect on the global agriculture than previously predicted meaning that the world hunger situation and Bangladesh's food security issues will only get worse.[9] The difference between historical and projected average temperatures each season throughout the world has revealed that harvests from major staple crops could drop by 40 percent by the end of the 21st century due to high temperatures in the growing seasons. A research study predicted this by using the patterns and characteristics of 23 global climate models. Not only are the harvests affected, the grain yield is also predicted to decrease anywhere from 3 to 15 percent.[10] The overall damage:

- Half of the districts were affected

Flood in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Flood in Dhaka, Bangladesh - 100,000 square kilometres (39,000 sq mi) (66%) of the country was overwhelmed

- 1,050 deaths reported

- 30 million people affected

- 25 million people left homeless

- 26,000 livestock lost

- 20,000 education facilities damaged

- 300,000 wells damaged

- 16,000 kilometres (9,900 mi) of roads flooded

- 4,500 kilometres (2,800 mi) of river embankments destroyed

- 32 percent of the total population affected[11]

What is most unfortunate about Bangladesh's flood catastrophe is the fact that its people are largely blameless for the rise of global warming, yet they experience the worst of its escalating effects.[12]

Flood preparation

Yearly flooding during monsoon season and other forms of inclement weather have forced the people of Bangladesh to adjust their lifestyle in order to prepare for the worst. One thing that people are doing to avoid the effects of the flooding is building elevated houses and roads. The raised houses are built on platforms raised above the typical water level a flood can reach. In many cases, neighbourhoods of people build these raised homes and roads, creating a "cluster village" which is essentially a village that is raised above flood level. This has proven to be very effective at avoiding the immediate effects of flooding.[13]

Additionally, organisations such as the Global Fund for Children and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have taken the initiative of helping kids rebuild their lives after natural disasters by building schools that function on boats themselves. "Floating schools", as these classrooms are known, help provide an education for children whose lives were drastically affected by the effects of constant flooding. Furthermore, children who even prior to a natural disaster did not receive proper schooling benefited from the opening of floating schools, making these communities into beneficial learning spots.[14]

However, there are effects from flooding that cannot be avoided simply by raising houses above flood level. Water contamination, for example, is very difficult to cope with during floods. Because of this, many people in Bangladesh use a tube well, which is a well with a top that is raised high enough that contaminated flood water from a flood cannot enter it. Many cities also have flood shelters, which are large raised platforms where people can find refuge from the effects of the on-rushing flood.[13] As a result of several demanding summer floods, in 2004, the government of Bangladesh made the step of seeking foreign aid rather than try to assist the millions of homeless people on their own. Nearly all the 147 million people living in Bangladesh at the time (crammed into a space the size of Iowa) were forced to adapt to intense rainfall and water-borne disease exposed conditions. An increase of salinity, a lack of food distributors, and the effects of seeing slum dwellers survive on flood water were just the initial blows to a monumental flood season that summer, extending beyond Bangladesh's borders and affecting India, China, Nepal, and Vietnam as well.[11]

These may be great solutions to the problem of flooding, but some cities do not have raised houses or flood shelters. These cities typically have rescue boats that can search for people who were unable to get above flood level and help them get out of the water. These boats are very important; they rescue over a thousand people over the course of multiple years.[13]

Coverage of inundation and deaths in major floods, 1954-1998

| Year | Flooded area (km2) | Percentage of total area | Number of deaths |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1954 | 36920 | 25 | 112 |

| 1955 | 50700 | 34 | 129 |

| 1956 | 35620 | 24 | |

| 1962 | 37404 | 25 | 117 |

| 1963 | 43180 | 29 | |

| 1968 | 37300 | 25 | 126 |

| 1970 | 42640 | 28 | 87 |

| 1971 | 36475 | 24 | 120 |

| 1974 | 52720 | 35 | 1987 |

| 1984 | 28314 | 19 | 513 |

| 1987 | 57491 | 39 | 1657 |

| 1988 | 77700 | 52 | 2379 |

| 1998 | 100000 | 67 | 1050 |

Table of flood damage in Bangladesh (1953-1998)

| Year | Crop damage (million tons) | Total financial loss (million taka) |

|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 0.6 | |

| 1954 | 0.7 | 1500 |

| 1956 | 0.5 | 1580 |

| 1962 | 1.2 | 1500 |

| 1966 | 1.0 | 600 |

| 1968 | 1.1 | 1200 |

| 1969 | 1.0 | 1100 |

| 1970 | 1.2 | 1000 |

| 1974 | 1.4 | 20000 |

| 1980 | 0.4 | 4000 |

| 1984 | 0.7 | 4500 |

| 1987 | 1.5 | 35000 |

| 1988 | 3.2 | 40000 |

| 1998 | 4.5 | 142160 |

See also

References

- H. Brammer (March 1990). "Floods in Bangladesh: Geographical Background to the 1987 and 1988 Floods". The Geographical Journal. 156 (1): 12–22. doi:10.2307/635431. JSTOR 635431.

- Mohd Shamsul Alam (2012), "Sea Level", in Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.), Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.), Asiatic Society of Bangladesh

- Uddin, Kabir; Matin, Mir A.; Meyer, Franz J. (2019-07-03). "Operational Flood Mapping Using Multi-Temporal Sentinel-1 SAR Images: A Case Study from Bangladesh". Remote Sensing. 11 (13): 1581. Bibcode:2019RemS...11.1581U. doi:10.3390/rs11131581.

- Md. Mizanur Rahman; Md. Amirul Hossain; Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya. "Flood Management in the Flood Plain of Bangladesh".

- 1988 Flood Archive

- Bangladesh floods recede, but death toll rises, 17 September 1998

- "World: South Asia Bangladesh floods rise again", BBC News, 24 August 1998

- Nishanthi Priyangika (20 October 1999), Hundreds of thousands hit by Bangladesh floods, wsws.org, retrieved 27 August 2015

- "How dire climate displacement warnings are becoming a reality in Bangladesh". The New Humanitarian. 2019-03-05. Retrieved 2019-06-24.

- Sunny, Sanwar (2011). Green Buildings, Clean Transport and the Low Carbon Economy: Towards Bangladesh's Vision of a Greener Tomorrow. Germany: LAP Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-8465-9333-2.

- Amy Waldman (30 July 2004). "Bangladesh Now Seeks Foreign Aid For Flooding". The New York Times.

- Hazel Healy (April 2012). "Ready or Not". New Internationalist. pp. 14–22 – via EBSCO's Academic Search Complete.

- "Bangladesh: Preparing for Flood Disaster". Oxfam. Archived from the original on 17 May 2014.

- Amy Yee (1 July 2013). "'Floating Schools' Bring Classrooms to Stranded Students". The New York Times.

- Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University, Vol 8, No. 1, Page: 56, March 2003

- Journal of the Faculty of Environmental Science and Technology, Okayama University Vol 8, No. 1, Page: 59, Table 5. March 2003

Further reading

- Jha, Abhas Kumar, Robin Bloch, and Jessica Lamond. Cities and Flooding: A Guide to Integrated Urban Flood Risk Management for the 21st Century. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, 2012. Academia. Web. 29 Apr. 2014.

- Hofer, Thomas, and Bruno Messerli. Floods in Bangladesh: History, Dynamics and Rethinking the Role of the Himalayas. Tokyo: United Nations UP, 2006. Academia. Web. 29 Apr. 2014.

External links

- "Flood Fury: A Recurring Hazard" (PDF). Focus. World Health Organization (WHO). 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2012.

- M Aminul Islam (2012). "Flood Action Plan". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.