Flash-lamp

The electric flash-lamp uses electric current to start flash powder burning, to provide a brief sudden burst of bright light. It was principally used for flash photography in the early 20th century but had other uses as well. Previously, photographers' flash powder, introduced in 1887 by Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke, had to be ignited manually, exposing the user to greater risk.

1903 view camera

Invention

The electric flash-lamp was invented by Joshua Cohen (a.k.a. Joshua Lionel Cohen of the Lionel toy train fame) in 1899, and by Paul Boyer in France.[1] It was granted U.S. patent number 636,492.[2] This flash of bright light from the flash-lamp was used for indoor photography in the late nineteenth century and the early part of the twentieth century.

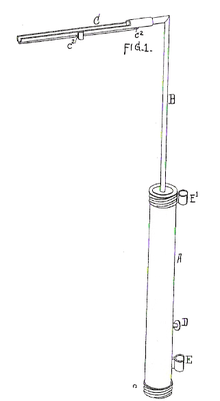

Joshua Lionel Cohen's flash-lamp patent 636,492 reads in part,

My appliance comprises a tubular casing A, to be held in the hand, an upright detachable post B, and a horizontal through part C to receive the flash-light powder. The casing A is adapted to contain cells of dry battery, which can be introduced into or removed from the lower end through an opening closed by the sheet-metal screw-cap c. The walls of the casing may be of metal and covered with leather or imitation leather or any other suitable material. At the upper end one pole of the uppermost cell will be in contact with the insulated pin a', Fig. 2, while opposite the opposing pole of the lowermost cell lies a push-button contact D, on pressing which the circuit can be closed at that point to the metal casing.[2]

The principle of operation of the electrical flash-lamp is linked to the shutter of an early box camera: tripping the shutter ignites the flash powder and releases the potential energy of the exploding powder causing a bright flash for indoor photography.

Uses of flash-lamp

The main purpose of Cohen's invention was as a fuse to ignite explosive powder to get a photographer's flash.[3] One of the first practical applications, however, for Cohen's flash-lamp was as underwater mine detonator fuses for the U.S. Navy.[4][5][6][7][8][9] In 1899, the year the invention was patented, the government awarded Cohen a $12,000 contract for 24,000[10] naval mine detonator fuses.[11] The use of the flash for photography was dangerous, and photographers could get burned hands from the flash.[12]

Electric apparatus applications

A 1910 brochure for the Nesbit High Speed Flashlight Apparatus says,

"Raise up the movable plunger and spread the powder also over the bottom of the plunger chamber, under the head of plunger. Insert the electronic squib well into the hole for same, as shown by Fig. 7. Set up the camera and focus upon the object to be photographed. Set the flash outfit a little behind and the right side of the camera. Connect the plunger H by the wire G to the shutter prop in place under the shutter lever, so placing any wire directing screw eyes that the prop will be pulled away from the camera in such a direction as to not shake same. Set shutter at the desired speed, pull out slide, attach firing line to fuse leads, and insert plug on end of firing line into receptacle in end of battery carrying case. This connection should be made last to minimize danger of accidental discharge. A push on the button of the switch will now fire the powder."[13]

Footnotes

- Panthéon de la Légion d'honneur, vol. 2, by T. Lamathière

- Patent No. 636,492

- Beyer, p. 129 The navy thought it would make a great fuse for mines - which wasn't what Cowen had in mind - but he liked it fine when the government bought ten thousand of them.

- Aboutdotcom Cowen was an inventor of sorts; he developed a fuse to ignite photographic flash powder. Though the invention failed in its intent, the U.S. Navy bought up the fuses to use with underwater explosives.

- Joshua Lionel Cowen at a glance In 1899, he patented a device for igniting photographers’ flash powder by using dry cell batteries to heat a wire fuse. Cowen than parlayed this into a defense contract to equip 24,000 Navy mines with detonators.

- Invention & Technology Magazine In the 1890s Cowen invented several devices that could be powered by the newly available dry-cell batteries. One was a fuse for igniting photographic flash powder. The Navy ordered 24,000 of them to use as detonators for underwater mines.

- The Lionel Story Archived 2011-10-08 at the Wayback Machine In 1899, he patented a device for igniting photographers’ flash powder by using dry cell batteries to heat a wire fuse. Cowen than parlayed this into a defense contract to equip 24,000 Navy mines with detonators.

- The History of the Flashlight Archived 2009-01-07 at the Wayback Machine Cowen was an inventor of sorts; he developed a fuse to ignite photographic flash powder. Though the invention failed in its intent, the U.S. Navy bought up the fuses to use with underwater explosives.

- This day in Jewish History Joshua Lionel Cowen passed away. Born in 1880, he was the American inventor of electric model trains who founded the Lionel Corporation (1901), which became the largest U.S. toy train manufacturer. At age 18, he had invented a fuse to ignite the magnesium powder for flash photography, which the Navy Department bought from him to be a fuse to detonate submarine mines.

- The New Yorker magazine, Dec 13, 1947, p. 42

- Joshua Lionel Cowen at a glance

- Kobre, Kenneth. Photojounalism: The Professionals' Approach. Litton Educational Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0-930764-15-3.

- Nesbit - High Speed Flashlight Apparatus for Indoor Service, published by Allison & Hadaway (New York City) Booklet No. 2, 1910

Bibliography

- Beyer, Rick, The Greatest Stories Never Told - 100 Tales from History to Astonish, Bewilder & Stupefy, The History Channel, 2000, ISBN 0-06-001401-6