Flap (surgery)

Flap surgery is a technique in plastic and reconstructive surgery where any type of tissue is lifted from a donor site and moved to a recipient site with an intact blood supply. This is distinct from a graft, which does not have an intact blood supply and therefore relies on growth of new blood vessels. This is done to fill a defect such as a wound resulting from injury or surgery when the remaining tissue is unable to support a graft, or to rebuild more complex anatomic structures such as breast or jaw.[1]

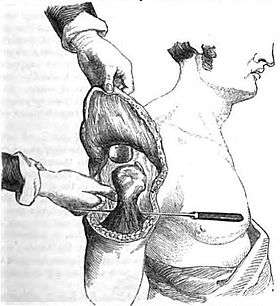

| Flap surgery | |

|---|---|

A flap used to cover an amputation stump | |

| ICD-9-CM | 86.7 |

Anatomy

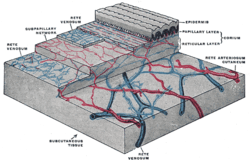

The skin can be divided into three main layers including the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous tissue. Blood is supplied to the skin mainly by two networks of blood vessels. The deep network lies between the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue, while the shallow network lies within the papillary layer of the dermis.[2] The epidermis is supplied by diffusion from this shallow network and both networks are supplied by collaterals, and by perforating arteries that bring blood from deeper layers either between muscles (septocutaneous perforators) or through muscles (musculocutaneous perforators). This redundant and robust blood supply is important in flap surgery because part of the supply will be cut off. The remaining blood supply must then keep the tissue alive until a more optimal supply can be restored through angiogenesis.[3]

An angiosome is a three-dimensional region of tissue that is supplied by a single artery and can include skin, soft tissue, and bone.[4] Adjacent angiosomes are connected by narrower choke vessels and so multiple angiosomes can be supplied by a single artery. Knowledge of these supply arteries and their associated angiosomes is useful in planning the location, size, and shape of a flap.[3]

Classification

Flaps can be fundamentally classified by their level of complexity, the types of tissues present, or by their blood supply.

Complexity

Flaps can be classified according to level of complexity. The surgeon should choose the least complex type that will achieve the desired effect, a concept known as the reconstructive ladder.[5]

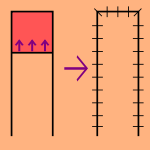

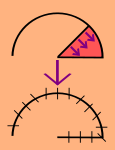

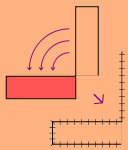

Local flaps

Local flaps are created by freeing a layer of tissue and then stretching the freed layer to fill a defect. This is the least complex type of flap and includes advancement flaps, rotation flaps, and transposition flaps, in order from least to most complex. With an advancement flap, incisions are extended out parallel from the wound, creating a rectangle with one edge remaining intact. This rectangle is freed from the deeper tissues and then stretched (or advanced) forward to cover the wound. The flap is disconnected from the body except for the uncut edge which contains the blood supply which feeds in horizontally. A rotation flap is similar except instead of being stretched in a straight line, the flap is stretched in an arc. The more complex transposition flap involves rotating an adjacent piece of tissue, resulting in the creation of a new defect which must then be closed.[3]

Regional flaps

Regional or interpolation flaps are not immediately adjacent to the defect. Instead, the freed tissue "island" is moved over or underneath normal tissue to reach the defect to be filled, with the blood supply still connected to the donor site via a pedicle.[6] This pedicle can be removed later on after new blood supply has formed, e.g., PMMC, DP flaps for head and neck defects, TRAM for breast reconstruction.[3]

Distant flaps

Distant flaps are used when the donor site is far from the defect. These are the most complex class of flap. Direct or tubed flaps involve having the flap connected to both the donor and recipient sites simultaneously, forming a bridge. This allows blood to be supplied by the donor site while a new blood supply from the recipient site is formed. Once this happens, the "bridge" can be disconnected from the donor site if necessary, completing the transfer.[7] A free flap has the blood supply cut and then reattached microsurgically to a new blood supply at the recipient site.[8][9]

Tissue type

Here are some of the more common classifications by tissue type:

- Cutaneous flaps contain the full thickness of the skin and superficial fascia and are used to fill small defects.

- Fasciocutaneous flaps add subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia, resulting in a more robust blood supply and ability to fill a larger defect.

- Musculocutaneous flaps further add a layer of muscle to provide bulk that can fill a deeper defect.

- Muscle flaps can provide bulk or functional muscle. If skin cover is needed, a skin graft can be placed over it.

- Bone flaps are used to replace bone, such as in jaw reconstruction.[3][10]

Vascular

Classification based on blood supply to the flap:

- Axial flaps are supplied by a named artery and vein. This allows for a larger area to be freed from surrounding and underlying tissue, leaving only a small pedicle containing the vessels.

- Reverse-flow flaps are a type of axial flap in which the supply artery is cut on one end and blood is supplied by backwards flow from the other direction.

- Random flaps are simpler and have no named blood supply. Rather, they are supplied by generic vascular networks.[2][3]

- Pedicled flaps remain attached to the donor site via a pedicle that contains the blood supply, in contrast to a free flap as described under Classification by complexity.[1]

See also

References

- Song, David H.; Ginard Henry; Russell R. Reid; Liza C. Wu; Garrett Wirth; Amir H. Dorafshar (2007). "Chapter 2: Grafts and Flaps". Plastic Surgery: Essentials for Students. Plastic Surgery Education Foundation.

- Clark JM, Wang TD. Local flaps in scar revision. Facial Plast Surg 2001; 17(4):295–308.

- Guyuron, Bahman; Elof Eriksson; John A. Persing (2009). "Chapter 8: Flaps". Plastic Surgery: Indications and Practice. 1. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4081-1.

- Houseman ND, Taylor GI, Pan WR. The angiosomes of the head and neck: anatomic study and clinical applications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000; 105(7):2287–2313.

- Turner AJ, Parkhouse N. Revisiting the reconstructive ladder. Plast Reconst Surg 2006; 118(1):267–268.

- Mellette JR, Ho DQ. Interpolation flaps. Dermatol Clin 2005; 23(1):87–112.

- Tschoi M, Hoy FA, Granick MS. Skin flaps. Clin Plast Surg 2005; 32(2):261–273.

- Guyuron, Bahman; Elof Eriksson; John A. Persing (2009). "Chapter 9: Microsurgery and Free Flaps". Plastic Surgery: Indications and Practice. 1. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-4081-1.

- Wolff/Hölzle. Raising of Microvascular Flaps. A Systematic Approach. Springer 2011.

- Cormack GC, Lamberty BGH. The arterial anatomy of skin flaps. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1986.