Bisinus

Bisinus (sometimes shortened to Bisin) was the king of Thuringia in the 5th century AD or around 500. He is the earliest historically attested ruler of the Thuringians. Almost nothing more about him can be said with certainty, including whether all the variations on his name in the sources refer to one or two different persons. His name is given as Bysinus, Bessinus or Bissinus in Frankish sources, and as Pissa, Pisen, Fisud or Fisut in Lombard ones.[1]

History

Bisinus was the first husband of Menia,[2] a fact attested only in the Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani.[3][4] He had a daughter, Raicunda, who became the first wife of the Lombard king Wacho (c. 510–540),[5] a fact attested in all three of the main Lombard chronicles (two of which specify that he was king of the Thuringians).[6][7][8] Menia later married a man (unnamed in the sources) of the Gausus family and became the mother of Audoin, who in 540 became the regent of Wacho's son by his third wife, Walthari, and then succeeded him to the throne in 546.[2]

Bisinus was also the father of the three brothers who ruled Thuringia in the 520s and 530s: Hermanafrid, Bertachar and Baderich.[9] Bertachar had a daughter, Radegund, who founded Holy Cross Abbey in Poitiers and was recognised as a saint. She died in 587. Two hagiographies of her were produced by her friends Baudovinia and Venantius Fortunatus.[10][11] Fortunatus specifies that she was "from the Thuringian region", a daughter of King Bertachar and granddaughter of King Bisinus.[12]

While most scholars accept that the Thuringian kings called Bisinus in the Frankish sources and Pissa in the Lombard ones are one and the same, Martina Hartmann rejects the identification and points out that the Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire makes no such identification either.[13]

Gregory of Tours

Gregory of Tours, writing in the last quarter of the 6th century, says that when the Franks rebelled against their king, Childeric I, who was accused of seducing their daughters, he went into exile at the court of Bisinus in Thuringia for eight years. In his absence, the Franks elected the Roman commander Aegidius as their king.[14] Childeric's exile corresponds to the period between Aegidius' appointment as magister militum for Gaul in 456 or 457 and his death in 465.[14][15] When Childeric returned from exile, Bisinus' wife Basina abandoned her husband to go with him. She became his wife and the mother of Clovis I.[14] Gregory does not describe Bisinus as king of the Thuringians or even as a Thuringian himself, but as king "in Thuringia".[16] Gregory's account was used by the authors of the 7th-century Chronicle of Fredegar[17] and the 8th-century Book of the History of the Franks.[18]

Scholars have been skeptical of Gregory's account. It has been called a "folk tale", albeit one that corresponds well chronologically to the dates of Aegidius' magistracy.[14] It has been suggested that Gregory in fact confused the civitas Tungrorum (today Tongeren) in northern Gaul with Thuringia and that Childeric was exiled to Tongeren. It has even been suggested that Gregory, knowing only that the name of Clovis' mother was Basina and that an early king of Thuringia was named Bisinus, invented the relationship between Basina and Bisinus based on the similarity of their names (having already, possibly erroneously, presumed the location of exile to be Thuringia).[10] Although most scholars accept Childeric's exile as historical, Berthold Schmidt rejected Gregory's entire account of it as a fiction.[19]

It is highly unlikely (but not impossible) that the Bisinus of Gregory and the Bisinus of the Lombard chronicles are one and the same.[2] In that case Bisinus would have been married to Basina almost eighty years before his youngest son's death in battle and had a living grandchild in 587.[19][20] Taking Gregory's account as historical, it has been suggested therefore that there were in fact two kings named Bisinus. Bisinus (II), husband of Menia, may then have been the nephew of Bisinus (I), husband of Basina.[9] The alternative is that Gregory misused the name of the historical Bisinus, husband of Menia and grandfather of Radegund, in reconstructing the events of the 460s.[10]

Location of kingdom

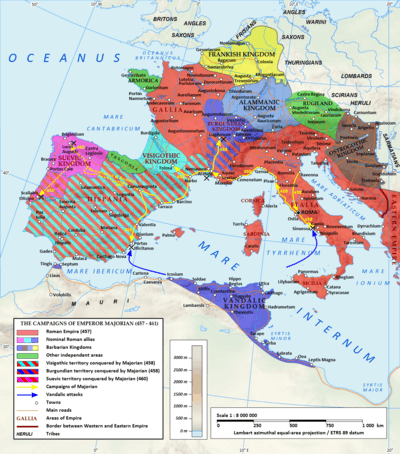

The location of Bisinus' kingdom is a matter of some debate. Usually it is located in the place of present-day Thuringia, well to the east of the Rhine. An artefact that may be associated with Basina was found in the vicinity of Weimar: a silver ladle engraved with the name Basena that may date to the 5th century.[21] The heartland of 5th-century Thuringia, however, may have initially been west of the Rhine, with the kingdom only expanding eastward in the decades after Bisinus' reign. The 12th-century Liber de compositione castri Ambaziae et ipsius dominorum gesta records that Bisinus' territory lay on the banks of the Saône between Toul and Lyon. It also refers to Bisinus as a dux (duke) only and not as a king.[22]

Notes

- Weddige 1989, p. 10.

- Jarnut 2009, p. 281.

- Grierson 1941, p. 19n.

- Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani, p. 9: Mater autem Audoin nomine Menia uxor fuit Pissae regis.

- Jarnut 2009, p. 279.

- Origo Gentis Langobardorum, p. 4: Raicundam, filia Fisud [Fisut] regis Turingorum.

- Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani, p. 9: Ranigunda, filia Pisen regi Turingorum.

- Historia Langobardorum, p. 60: Habuit autem Waccho uxores tres, hoc est primam Ranicundam, filiam regis Turingorum.

- Jarnut 2009, p. 288, contains a family tree..

- Halsall 2001, p. 125.

- Jarnut 2009, pp. 283–84.

- Fortunatus, p. 365: Beatissima igitur Radegundis natione barbara de regione Thoringa, avo rege Bessino, patruo Hermenfredo, patre rege Bertechario.

- Hartmann 2009, p. 62, yet see p. 13, where she rejects Bisinus' marriage to Basina on the grounds that he was the husband of Menia.

- James 2014, p. 80.

- Martindale 1980, p. 244, dates the exile to c. 456–c. 464.

- Neumeister 2014, p. 90: in Thuringiam ... regem Bysinum.

- Pseudo-Fredegar, pp. 95 and 97.

- Liber Historiae Francorum, pp. 248–49, uses the spelling Bisinus.

- Halsall 2010, p. 196.

- Mladjov 2014, p. 564, presents a genealogical reconstruction in which Bisinus married first Basina and had his sons by her before marrying Menia, by whom he had Radegund, who is presented as his daughter rather than granddaughter.

- Wood 1994, pp. 37–40.

- Neumeister 2014, p. 88: Bissinus iste terram suam super Sunnam fluvium, qui alio nomine Arar dictur, a Tullo usque Lugdunum possidebat.

Sources

- Primary sources

- Gregorius Turonensis, Libri Historiarum X, eds. Bruno Krusch and Wilhelm Levison. MGH SS rer. Merov. 1, 1 (Hanover, 1951 [1885]).

- Historia Langobardorum codicis Gothani, ed. Georg Waitz. MGH SS rer. Lang. (Hanover, 1878), 7–11.

- Liber Historiae Francorum, ed. Bruno Krusch. MGH SS rer. Merov. 2 (Hanover, 1888), 215–328.

- Origo Gentis Langobardorum, ed. Georg Waitz. MGH SS rer. Lang. (Hanover, 1878), 1–6.

- Paulus Diaconus, Historia Langobardorum, ed. Georg Waitz. MGH SS rer. Lang. (Hanover, 1878), 12–187.

- Pseudo-Fredegar, Chronicarum quae dicuntur Fredegarii scholastici libri IV, ed. Bruno Krusch. MGH SS rer. Merov. 2 (Hanover, 1888), 1–193.

- Venantius Honoricus Clementianus Fortunatus, Vita Sanctae Radegundis, ed. Bruno Krusch. MGH SS rer. Merov. 2 (Hanover, 1888), 364–377.

- Secondary sources

- Grierson, Philip (1941). "Election and Inheritance in Early Germanic Kingship". Cambridge Historical Journal. 7 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1017/s1474691300003425.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halsall, Guy (2001). "Childeric's Grave, Clovis' Succession, and the Origins of the Merovingian Kingdom". In Ralph Mathisen; Danuta Shanzer (eds.). Society and Culture in Late Antique Gaul. Routledge. pp. 130–147.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halsall, Guy (2010). "Commentary Three: Once More Unto Saint-Brice". In Guy Halsall (ed.). Cemeteries and Society in Merovingian Gaul: Selected Studies in History and Archaeology, 1992–2009. Brill. pp. 188–197.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hartmann, Martina (2009). Die Königin im frühen Mittelalter. Kohlhammer Verlag.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Edward (2014) [2009]. Europe's Barbarians, AD 200–600. Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jarnut, Jörg (2009). "Thüringer und Langobarden im 6. und beginnenden 7. Jahrhundert". In Helmut Castritius; Dieter Geuenich; Matthias Werner (eds.). Die Frühzeit der Thüringer: Archäologie, Sprache, Geschichte. De Gruyter. pp. 279–290.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joye, Sylvie (2005). "Basine, Radegonde et la Thuringe chez Grégoire de Tours". Francia. 32 (1): 1–18.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, J. R., ed. (1980). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 2, AD 395–527. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mladjov, Ian (2014). "Barbarian Genealogies". In H. B. Dewing (trans.); Anthony Kaldellis (eds.). The Wars of Justinian by Prokopios. Hackett. pp. 560–566.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neumeister, Peter (2014). "The Ancient Thuringians: Problems of Names and Family Connections". In Janine Fries-Knoblach; Heiko Steuer; John Hines (eds.). The Baiuvarii and Thuringi: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell. pp. 83–102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steuer, Heiko (2009). "Die Herrschaftssitze der Thüringer". In Helmut Castritius; Dieter Geuenich; Matthias Werner (eds.). Die Frühzeit der Thüringer: Archäologie, Sprache, Geschichte. De Gruyter. pp. 201–234.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weddige, Hilkert (1989). Heldensage und Stammessage: Iring und der Untergang des Thüringerreiches in Historiographie und heroischer Dichtung. Max Niemeyer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wood, Ian N. (1994). The Merovingian Kingdoms, 450–751. Harlow: Longman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)