Figurism

Figurism was an intellectual movement of Jesuit missionaries at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th century, whose participants viewed the I Ching as a prophetic book containing the mysteries of Christianity,[1] and prioritized working with the Qing Emperor (rather than with the Chinese literati) as a way of promoting Christianity in China.[2]

Background

Since Matteo Ricci's pioneering work in China in 1583–1610, the Jesuit missionaries in China worked on a program of integrating Christianity with the Chinese traditions. Ricci and his followers identified three "sects" present in China – Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. While viewing Buddhism and Taoism as "pagan" religions inimical to Christianity, Ricci's approach – predominant with the Jesuits in China throughout most of the 17th century – viewed Confucianism as, essentially, a moral teaching that was compatible with, rather than contradictory to, the Christian beliefs. They viewed Confucian rites, such as those having to do with the veneration of the dead, as essentially civil functions meant to edify the people in virtuous morals, rather than as religious rites. On this basis the Jesuits centered their work in China on the interaction with the Chinese Confucian literati, trying to convince them of their theories and consequently convert them to the Christian faith. When addressing the European public, the China-based Jesuit missionaries strove to present Confucianism, as represented by its Four Books, in favorable light – the effort culminated with the publications of Confucius Sinarum Philosophus by Philippe Couplet (Paris, 1687).

After the fall of the Ming Dynasty (fall of Beijing in 1644) and the Manchu conquest of the entire country (by the early 1650s), the Jesuits in China had to switch their allegiance from the Ming Dynasty to the Manchu Qing, just as most of the Chinese literati eventually did. They soon found themselves working in a quite different intellectual and political environment than their predecessors during the Ming era. While in Ricci's days the Jesuits were not in a position to work directly with the emperor (the reclusive Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620) largely removed himself from the public life, and rarely gave audiences to anyone, even his own Grand Secretary), the early Qing emperors – Shunzhi, and in particular Kangxi – were not above dealing directly with the Jesuits and using their services for the needs of the central government.[3] On the other hand, the Chinese Confucian thought had changed as well: the more open outlook of the late-Ming literati was replaced in the early Qing period by widespread clinging to the Neo-Confucian orthodoxy, which was endorsed by the court as well, but had been traditionally disapproved by the Jesuits as "atheistic" and "materialistic".[4]

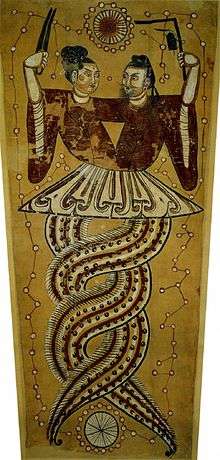

Accordingly, by the late 17th century the way whereby the China-based Jesuits strove to bridge the gap between China and Christian Europe had changed as well. Instead of praising Confucius and the ideology attributed to him, many Jesuits, led by Joachim Bouvet (who first arrived to China in 1688), focused on China's earliest classic, I Ching, which Bouvet viewed as the oldest written work in the world, containing "precious vestiges from the remains of the most ancient and excellent philosophy taught by the first patriarchs of the world".[5] The Figurists maintained the belief of the early Jesuit missionaries in China that China's ancient religion, now almost lost, was connected to the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Figurist tenets

The Figurists often disagreed with each other but generally they could agree on three basic tenets:

1. The Issue of Chronology

The first aspect that all Figurists agreed upon was the belief that a certain period in the Chinese history does not belong to the Chinese only but to all of mankind. The Jesuits furthermore believed that Chinese history dated back before the Flood and was therefore as old as European history. This made the Figurists believe that the two histories were equal in religious importance.

2. The Theory of Common Origin with Noah

After the great Flood, Noah’s son Shem moved to the Far East and brought with him the secret knowledge of Adam in original purity. Thus the Figurists believed that one could find many hidden allusions to pre-Christian revelation in the Chinese classics.

Bouvet also thought that Fu Xi, the supposed author of the I Ching, as well as Zoroaster and Hermes Trismegistus, were really the same person: the biblical patriarch Enoch.[6]

3. The Revelation of Messiah

The Figurists determined that the sage shengren (聖人) was in fact the Messiah. This proved in the minds of the Figurists that, for example, the birth of Jesus was foreshadowed in the Chinese classics as well.

Joachim Bouvet in particular focused his research on I Ching, trying to find a connection between the Chinese classics and the Bible. He came to the conclusion that the Chinese had known the whole truth of the Christian tradition in ancient times and that this truth could be found in the Chinese classics.

Opposition to the Figurists

There was opposition to the Figurists both in China and in Europe. In China, there was an anti-Western group of Chinese literati and officials. Some Chinese scholars doubted the idea that God was already part of the Confucian tradition. When Foucquet rejected the official Chinese history, he was angrily rejected by the Chinese and consequently ordered back to Europe.

In Europe there was also an anti-Jesuit group in the Catholic Church. The Figurist idea was seen as an especially dangerous innovation because it elevated the Chinese classics at the expense of Christian authorities. The Catholic Church did not accept the idea that the Chinese classics could be of importance to the Christian faith. (see: Chinese Rites controversy)

Influence and failure of the Figurists

Because of the overwhelming opposition to the Figurists, they were unable to publish any of their works during their lifetimes, except for Foucquet who got his major work published in 1729. However other aspects hampered the Figurists. There was no generally accepted concept for their research. Translations of texts from Chinese to Latin or the other way around took a long time. Most importantly, the Figurists did not agree among themselves. When the Catholic Church forbade the Rites and the Chinese started to persecute Christians, the Figurist mission faded along with it to become a mere footnote in the history of the Christian mission in China.

Representatives

- François Noël (1651–1729)[7]

- Joachim Bouvet (1656–1732)[8]

- Joseph-Henri-Marie de Prémare (1666–1735)

- Jean-François Foucquet (1665–1741)

- Jean-Alexis de Gollet (1664–1741)

References

Citations

- Mungello (1989), p. 309.

- Mungello (1989), 300–305.

- Mungello (1989), p. 305

- Mungello (1989), p. 305-307

- Bouvet's letter to Le Gobien and Leibniz, November 8, 1700; quoted in Mungello (1989), p. 314-315

- Mungello (1989), p. 321

- Lackner (1991), p. 145.

- Mungello (1989), p. 358.

Bibliography

- Lackner, Michael (1991), "Jesuit Figurism", China and Europe: Images and Influences [from the] Sixteenth to Eighteenth Centuries, Monograph Series, No. 12, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, pp. 129–150.

- Mungello, David Emil (1989), Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 0-8248-1219-0.