Fervaal

Fervaal, Op. 40, is an opera (action musicale or lyric drama) in three acts with a prologue by the French composer Vincent d'Indy. The composer wrote his own libretto, based in part on the lyric poem Axel[1] by the Swedish author Esaias Tegnér. D'Indy worked on the opera over the years 1889 to 1895,[2] and the score was published in 1895.

Background

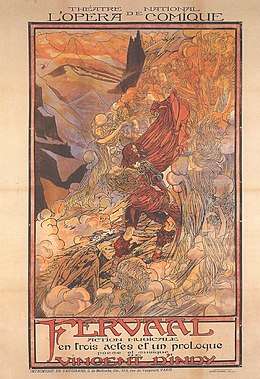

Fervaal premiered at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels on 12 March 1897. It was subsequently produced in Paris in 1898, and again in that city in 1912.[3] The first of 13 performances at the Théâtre National de l'Opéra-Comique (Théâtre du Châtelet), on 10 May 1898 was conducted by André Messager and included in the cast Raunay and Imbart de la Tour from the Brussels premiere, along with Gaston Beyle, Ernest Carbonne and André Gresse.[4]

The last stage performances of it occurred in 1912/13 (at the Paris Palais Garnier, again with Messager conducting) and since that time opera was never performed again on stage, but in concert it was presented by RTF in 1962.[5] The Bern Opera House presented it in two concert performances, conducted by Srboljub Dinić, on 28 May and 18 June 2009.[6] It was also performed in concert by the American Symphony Orchestra, led by Leon Botstein on 14 October 2009 at Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center in New York City.[7] The Festival de Montpellier revived the work in 2019 with Michael Spyres as Fervaal, Jean-Sébastien Bou as Arfagard and Gaëlle Arquez as Guilhen, with Michael Schønwandt conducting.[8]

Contemporary commentary, such as from Maurice Ravel, described Fervaal as strongly influenced by the operas of Richard Wagner.[9] such as Parsifal[10] Thus the opera can be described as an epic with Wagnerian allusion. Anya Suschitzky has published a lengthy analysis of the opera in the context of French nationalism and the influence of Wagner on French composers.[11] James Ross[12] has examined Fervaal in the context of French politics of the time, in addition to French nationalism.[13] Manuela Schwartz has discussed in detail the connection between the story of Axel and the opera of Fervaal.[14]

In the context of religious theme of paganism vs. Christianity in the work, d'Indy uses the old musical theme of "Pange, lingua" as a musical representation of the new religion (Christianity) supplanting the old (paganism).[15]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 12 March 1897[16] Conductor: Philippe Flon |

|---|---|---|

| Fervaal, Celtic chief | tenor | Georges Imbart de la Tour |

| Guilhen, Saracen | mezzo-soprano | Jeanne Raunay |

| Arfagard, Druid | baritone | Henri Seguin |

| Kaïto | contralto | Eugénie Armand |

| Lennsmor, priest | tenor | Paul Isouard |

| Grymping, priest | baritone | Hector Dufranne |

| Shepherd | Julia Milcamps | |

| Messenger | baritone | Cadio |

| Ilbert (Celtic chief) | tenor | Dantu |

| Chennos (Celtic chief) | tenor | Gillon |

| Ferkemnat (Celtic chief) | tenor | Victor Caisso |

| Gwelkingubar (Celtic chief) | bass | Henri Artus Blancard |

| Berddret (Celtic chief) | bass | Delamarre |

| Helwrig (Celtic chief) | bass | Charles Danlée |

| Geywhir (Celtic chief) | bass | Van Acker |

| Buduann (Celtic chief) | bass | Roulet |

| Penwald (Celtic chief) | bass | Verheyden |

| Edwig (Celtic chief) | tenor | Luc Disy |

| Moussah | tenor | Luc Disy |

| Peasants, Saracens, Priests and Priestesses, Bards, Warriors, off-stage voices | ||

Instrumentation

- woodwinds: 4 flutes (3rd and 4th doubling piccolos), 2 oboes, cor anglais, 3 clarinets (3rd doubling bass clarinet), bass clarinet (doubling contrabass clarinet), 4 bassoons, 4 saxophones (soprano, 2 altos and tenor)

- brass: 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 8 saxhorns (2 sopranino in E-flat, 2 soprano in B-flat, 2 alto in E-flat, 2 baritone in B-flat), 4 trombones, tuba, cornetto

- percussion: timpani, bass drum, triangle, cymbals, tamtam, two small gongs

- strings: 2 harps, 1st violins, 2nd violins, violas, violoncellos, contrabasses

Synopsis

In the prologue, Saracen bandits ambush the Gauls Fervaal and Arfagard, leaving them injured. Guilhen, daughter of the Saracen emir and a sorceress, saves them from death. Guilhen has immediately fallen in love with Fervaal, and offers to cure him. The prologue ends with Fervaal being carried to the palace of Guilhen.

In act 1, Arfagard explains to Fervaal the boy's history and upbringing. Fervaal is the son of a Celtic king, from the land of Cravann, and is destined as the last advocate of the old gods (the "Nuées). He is charged with the mission of saving his homeland from invasion and pillage, but must renounce love to fulfill his duty. Upon Guilhen's return, Fervaal returns her love. However, Arfagard calls for Fervaal to leave her and fulfill his mission. After he finally does take leave of Guilhen, she calls forth a mob of her fellow Saracens to revenge her abandonment by invading Cravann.

In act 2, Arfagard and Fervaal have returned to Cravann. They consult the goddess Kaito in the mountains, where she delivers this prophecy:

Si le Serment est violé, si la Loi antique est brisée,

si l'Amour règne sur le monde, le cycle d'Esus est fermé.

Seule la Mort, l'injurieuse Mort, appellera la Vie.

La nouvelle Vie naîtra de la Mort.

If the oath is violated, if the ancient law is broken,

if love reigns over the world, the cycle of Esus is closed.

Only death, injurious death, will call forth life.

From death, new life will be born.

Arfagard does not understand the meaning of the prophecy. Fervaal understands that the violation refers to his own breaking of the oath renouncing love, and that the redemptive death will be his in the end. Arfagard introduces Fervaal to the Cravann chiefs, and they hail him as their new commander, or "Brenn". Fervaal anticipates that he will fail as leader and thus as his land's saviour, but he feels that he can achieve his redemptive death in battle as military commander. Fervaal tries to explain this situation to Arfagard, who becomes fearful for his people's future.

In act 3, the Cravann army has lost in battle, and Fervaal remains alive, in spite of seeking death in the conflict. He then asks Arfagard to kill him as a sacrifice to fulfill his duty. However, Guilhen appears, which reawaken's Fervaal's love and causes him to change his mind. Arfagard tries to kill Fervaal, but Fervaal instead cuts down Arfagard. Fervaal takes Guilhen away from the battlefield and they begin to ascend a mountain. Exhausted, Guilhen dies in Fervaal's arms. Fervaal laments the deaths of both Guilhen and Arfagard. He then hears the wordless chorus singing the "Pange, lingua" melody. Fervaal carries the body of Guilhen up the mountain, as he realizes that the reign of the "new God" is forthcoming. As he disappears from the scene, an "ideal sun" begins to shine.

Recording

There has not been a complete commercial recording of Fervaal, although there have been several recordings of the Prelude:

- Brussels Royal Conservatory Orchestra; Désiré Defauw, conductor[17]

- L'Orchestre des Concerts Lamoureux; Albert Wolff, conductor, rec 1930

- San Francisco Symphony; Pierre Monteux, conductor, rec 27 January 1945, San Francisco

- Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; Charles Munch, conductor, rec 4 October 1947, Kingsway Hall, London

- Columbia Symphony Orchestra; Thomas Schippers, conductor

In 2004, the BBC broadcast as part of its "Composer of the Week" program a specially made recording of act 3 of Fervaal, with the following featured performers:

- David Kempster, bass/baritone; Christine Rice, mezzo-soprano; Stuart Kale, tenor; BBC National Chorus of Wales; BBC National Orchestra of Wales; Jean-Yves Ossonce, conductor. This BBC recording was not commercially released.

A full production by French radio was recorded on 22 March 1962 and broadcast on 19 October the same year, and it has been issued on the Malibran label (MR771), issued in 2015, its first commercial release.

- Jean Mollien: Fervaal; Micheline Grancher: Guilhen; Pierre Germain: Arfagard; Janine Capderou: the goddess Kaïto; Jean Michel: Edwig; Joseph Peyron: Chennos; Christos Grigoriou: Geywihr; Gustave Wion: Berddret; Lucien Lovano: Helwrig; Chorus and Lyric Orchestra of the ORTF; Pierre-Michel Le Conte, conductor.

References

- Huebner, Steven (2006). "Fervaal". French Opera at the Fin de Siècle: Wagnerism, Nationalism and Style. Oxford University Press, US. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-19-518954-4.

- Paul Landormy (October 1932). "Vincent d'Indy". The Musical Quarterly. XVIII (4): 507–518. doi:10.1093/mq/XVIII.4.507. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Calvocoressi, M.D. (1921). "The Dramatic Works of Vincent d'Indy. Fervaal" (1 June 1921)". The Musical Times. 62 (940): 400–403. doi:10.2307/908815. JSTOR 908815.

- Wolff, Stéphane. Un demi-siècle d'Opéra-Comique (1900–1950). Paris: André Bonne, 1953, p. 228. OCLC 44733987, 2174128, 78755097

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."List of performances of Fervaal". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- The poster for Bern's Opera House performances of Fervaal Archived 2011-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Review of Fervaal performance at Avery Fisher Hall 2009

- Laurent, François. D'Indy, le retour. Diapason, September 2019, No. 682, p. 68.

- Huebner, Steven (2003). "Review: Wagner-Rezeption und französische Oper des Fin de siècle: Untersuchungen zu Vincent d'Indys Fervaal". Music & Letters. 84 (4): 668–670. doi:10.1093/ml/84.4.668. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Hill, Edward Burlingame (1915). "Vincent d'Indy: An Estimate". The Musical Quarterly. 1 (2): 246–259. doi:10.1093/mq/I.2.246. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Suschitzky, Anya (Fall–Spring 2001–2002). "Fervaal, Parsifal, and French National Identity". 19th-Century Music. 25 (2–3): 237–265. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.25.2-3.237. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - James Ross web page

- Ross, James (2003). "D'Indy's Fervaal: Reconstructing French Identity at the 'Fin de Siècle'". Music & Letters. 84 (2): 209–240. doi:10.1093/ml/84.2.209. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- Schwartz, Manuela (1998). "Symbolic structures and elements in the opera Fervaal of Vincent d'Indy". Contemporary Music Review. 17 (3): 43–56. doi:10.1080/07494469800640191.

- Calvocoressi, M.D. (1 July 1921). "The Dramatic Works of Vincent d'Indy. Fervaal (Continued)". The Musical Times, 62, 941: 466–468.

- Fervaal premiere cast, Carmen website of La Monnaie], accessed 16 June 2014

- "Discus" (pseudonym) (November 1, 1930), "Gramophone Notes". The Musical Times, 71 (1053): 995–998.