Fernão de Loronha

Fernão de Loronha (c. 1470 or earlier – c. 1540), whose name is often corrupted to Fernando de Noronha or Fernando della Rogna, was a prominent 16th-century Portuguese merchant of Lisbon, of Jewish descent. He was the first charter-holder (1502–1512), the first donatary captain in Brazil and sponsor of numerous early Portuguese overseas expeditions. The islands of Fernando de Noronha off the coast of Brazil, discovered by one of his expeditions and granted to Loronha and his heirs as a fief in 1504, are named after him.

Fernão de Loronha | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1470 |

| Died | c. 1540 (aged 69–70) Lisbon, Portugal |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Merchant |

Biography

Fernão de Loronha was a Sephardi Jew converted to Catholicism (cristão-novo). He was the son of Martim Afonso de Loronha and the brother of another Martim Afonso de Loronha, a clerk of the Order of Christ, both ennobled and granted a Coat of Arms newly created. He married Violante Rodrigues.[1]

By 1500, Fernão de Loronha was a well-established merchant in Lisbon, where he served as the factor of Jakob Fugger, head of the wealthy German banking family of Augsburg. In his 1504 royal letter, King Manuel I of Portugal referred to Loronha as a knight of the royal household (cavaleiro da nossa casa). His acquisition of status at a time when even wealthy and notable Jews came under persecution in Portugal suggests Loronha had unusually high connections. Even the corruption of his name from Loronha to Noronha might not be accidental, but reflect a popular assumption (which he might not have been eager to correct) that he was connected to the Noronha clan, one of the most illustrious noble families in Portugal, of royal Castilian descent (although there is no evidence Loronha had any ties, by blood or marriage, to the Noronhas).[2]

After the discovery of Brazil by Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500, the Portuguese crown sent out a follow-up mapping expedition in 1501 to explore the Brazilian coast. The commander of this expedition is unknown, but it was accompanied by Amerigo Vespucci, who wrote an account of it.[3] Some scholars believe that Fernão de Loronha may have actually been the overall captain of this expedition, although others believe it unlikely a prominent and wealthy merchant like Loronha would absent his businesses to go personally command vessels himself, that Loronha's support (if any) was probably only financial.[4]

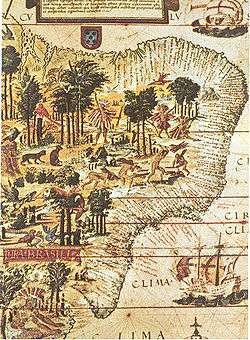

The mapping expedition explored much of the Brazilian eastern coast from Cape São Roque in the northeast down to the environs of Cabo Frio and named many of the locations along the way. Returning to Lisbon by September 1502, the expedition reported the discovery of an abundance of brazilwood (pau-brasil) on the coast.[5] Brazilwood was highly valued by the European cloth industry as a superb dye, producing a deep red color, but it had to be imported from India at great expense.[5] Sensing the commercial opportunity of the new discovery, Fernando de Loronha assembled a consortium of Lisbon merchants, with himself at its head, and petitioned the crown for permission to exploit the find. In late September 1502, King Manuel of Portugal issued a charter (now lost) granting Fernão de Loronha the exclusive right to the commercial exploitation of the "Lands of Vera Cruz" (as Brazil was then known) for a period of three years. In return, Loronha was obliged to outfit and send six ships per year at his own expense, commit himself to discover 300 leagues of new coast per year and build a fort (forteza) in the new country. Loronha would also obliged pay the crown a share of his revenues: zero in the first year, one-sixth in the second year, and one quarter in the third year.[6] However, a different account reports Loronha was given a ten-year charter, for which he paid the crown a fixed sum of 4,000 ducats per year.[7] One possible reconciliation is that the latter reflect not the original terms, but new terms that were negotiated upon the renewal of Loronha's charter in 1505.[8]

In April–May 1503, Loronha's consortium outfitted a new expedition of six ships under captain Gonçalo Coelho, accompanied once again by Amerigo Vespucci, to scout the Brazilian coast and set up harvesting warehouses. On August 10, 1503, the expedition stumbled on an uninhabited island off the northeast Brazilian coast that is now called the Fernando de Noronha island. However, it went through different names at that time: Vespucci called it São Lourenço, official documents called it São João, while a contemporary map, the Cantino planisphere, apparently called it Quaresma.[9]

The Coelho-Vespucci expedition was instructed by Loronha to establish factories (feitorias, essentially warehouses) along the coast as collection points for brazilwood harvests. It is believed three warehouses were established on this expedition - one by Vespucci at Cabo Frio (manned by 24 men, thus filling the forteza requirement), another by Coelho at Porto Seguro (feitoria da Santa Cruz de Cabrália) and probably a third, also by Coelho, in Guanabara Bay (feitoria da Carioca). Around 1509 or 1511 (details uncertain), an expedition outfitted by Fernão de Loronha under Cristóvão Pires established another brazilwood factory at Baía de Todos os Santos (modern Bahia). It is believed a factory may have also been established at São Vicente around 1508 or so, although this is more speculative.

On January 14, 1504, King Manuel I of Portugal issued a royal letter granting the island of São João (Fernando de Noronha) personally to Fernão de Loronha and his descendants, thereby making Loronha the first Portuguese hereditary donatary captain of Brazil.[10] A factory was immediately set up on the island, and quickly became the hub of Loronha's operation - brazilwood harvested directly across the water, or ferried in by small boats from the factories down the coast, were collected on the island, and dispatched on larger ships back to Portugal. By 1506, Loronha's consortium is said to have reaped a brazilwood harvest of 20,000 quintals by 1506, representing a 400-500% profit over the initial lump sum payment and ship expenses. Loronha also drummed up some business in 'novelty' pets like colorful Brazilian parrots and monkeys, cotton and occasionally, Indian slaves.

Loronha's enterprise, run with only a bare minimum of staff, was not known to employ coercion. Brazilwood and other products were acquired by trade with indigenous peoples. Brazilian Indians (mostly Tupi) did all of the woodcutting independently and delivered the harvest to the warehouses, where they traded with Loronha's agents for iron goods, tools, knives, axes, mirrors, and other miscellaneous products of that kind. The slaves were not acquired in raids, but by ransoming war captives from local tribes (although this proved tricky, given the embedded tradition of cannibalism among the Tupi, local chieftains were reluctant to sell their 'sacred' prisoners.)

Loronha's commercial charter was renewed in 1506, and then again until 1512, when the crown passed the charter to a different merchant consortium, led by Jorge Lopes Bixorda. In 1515, the Portuguese crown let Bixorda's charter expire, and finally took over the factories and the brazilwood trade itself. By this time, Spanish and French interlopers (the latter mainly outfitted by merchants from the Atlantic ports of Brittany and Normandy, connected to the cloth trade), had begun to visit the Brazilian coast with some regularity, landing brazilwood-harvesting parties and/or plundering the stores from the lightly manned Portuguese factories along the coast. As private Portuguese merchants did not have the wherewithal (nor the authority) to challenge the foreign interlopers, the losses were heavy. When the Portuguese crown took over the enterprise, it immediately set up a military coastal patrol to defend these locations. Despite losing its commercial charter, Loronha's family retained its hereditary capitaincy of Fernando de Noronha island (heirs are confirmed in documents down to 1580).[11]

Independently of his Brazilian activities, Fernão de Loronha also participated in the outfitting of the Portuguese India Armadas of the early 1500s. The Bassas da India in the Mozambique Channel is named after one of Loronha's ships, the Judia ("Jewess"), which discovered the atoll by running into it in 1506. The original name baixas da Judia ("Judia Shoals") was corrupted into "bassas da India" by later error.

Naming Brazil

If anyone is responsible for the naming of Brazil and its inhabitants, it would be Fernão de Loronha. Although officially named the lands of Vera Cruz or Santa Cruz by the original discovers, it was during Loronha's tenure that the name of the land gradually transitioned to Terra do Brasil and its inhabitants to Brasileiros. Some unkind authors claim that Loronha, on account of his Jewish roots, was uncomfortable with referring to the land after the True Cross. But the truth is probably more mundane. It was rather common for 15th- and 16th-century Portuguese to refer to distant lands by their commercial product rather than their proper name (e.g. Madeira Islands, Pepper Coast, Ivory Coast, Gold Coast, Spice Islands, etc.) The lands of Vera Cruz were simply popularly known as the "Land of Brazil" (Terra do Brasil) for the same reason. (Curiously, some letters from the early 1500s refer to it as Terra di Papaga, "Land of Parrots"[12])

More curious is the demonym. In the Portuguese language, an inhabitant of Brazil is referred to as a Brasileiro, although the suffix -eiro properly denotes occupations and not inhabitants (who are typically given the suffix -ano instead). A rough English equivalent might be the suffix -or (doctor, actor) or -er (carpenter, plumber) versus -an (Indian, American). Thus an inhabitant of Brazil should have become known in Portuguese as a Brasiliano ("Brazilian"), but – uniquely among Portuguese demonyms – they are instead referenced as a Brasileiro ("Braziler"). This stems from Loronha's tenure when brasileiro was indeed a reference to an occupation: a brazilwood cutter or trader. The name of the occupation was simply gradually extended to refer to all the inhabitants of the land.

Notes

- http://www.geneall.net/P/per_page.php?id=205679 Fernão de Noronha in a Portuguese Genealogical site

- Greenlee (1945: p.8-9)

- Amerigo Vespucci relates the account of this expedition twice - first in a letter to Lorenzo Pietro Francesco di Medici, written in early 1503 (see (account) in Letter do Medici), and then again in his letters to Piero Soderini, written 1504-05 ([account] in Letter to Soderini).

- Proponents of the hypothesis that Loronha commanded the 1501 mapping expedition include Duarte Leite (1923) and Greenlee (1945). Opponents include Roukema (1963).

- Vogt (1967)

- The original charter is now lost. The terms, however, were reported in a letter dated October 3, 1502, by Piero Rondonelli. See Greenlee (1945: p.9) and Vogt (1967:p.154-5)

- This is reported in a letter of Leonardo de Ca' Masser in 1506/07. See Vogt (1967)

- Vogt (1967), however, believes Ca' Masser's letter is entirely in error, and that the terms reported by Rondinelli were probably the correct ones and there might not have been a renewal at all.

- One solution to the puzzle of multiple names, proposed by Roukema (1963) is the island's first name, São Lourenço, was given by Vespucci on the outward voyage of the Coelho expedition, on account of August 10, 1503, the day of discovery, being the feast day of St. Lawrence. It was renamed São João because of the "rediscovery" of that island on the return leg by another ship of the Coelho fleet (captain unknown, but not Vespucci, who returned by a different route), on August 29, 1503, the feast day of the beheading of St. John the Baptist. This other ship reached Lisbon in late 1503, and reported it as São João, the name by which it is referred to in a January 1504 document, well before Vespucci's own arrival back in Lisbon in September 1504 could correct it. As for Cantino map's Quaresma (meaning Lent), may be simply a mistake, that Quaresma was the name given to the Rocas Atoll, discovered during the 1501 mapping expedition, and not Fernando de Noronha island.

- An actual copy of this charter has never been found. Its contents and date, however, are summarized in a royal letter of March 3, 1522, confirming it. A copy of Loronha's captaincy charter is found in António Zeferino Cândido, editor (1900) Brazil: 1500-1900, Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional, p.392. A later royal letter of May 20, 1559, issued to Loronha's descendants, identifies the location of São João unambiguously as Fernando de Noronha island. See Duarte Leite (1923: p.276-8) and Roukema (1963: p.21).

- See Cândido, Brazil, p.393

- e.g. a letter of Giovanni Matteo Cretico (June 27, 1501) and a diary entry of Marino Sanuto (Oct 12, 1502) call it "Terra di Papaga'"; on-board diarist Thomé Lopes (1502, p.160) refers to it as the "Ilha dos Papagaios vermelhos" ("island of the red parrots").

References

- Duarte Leite (1923) "O Mais antigo mapa do Brasil" in História da Colonização Portuguesa do Brasil, vol.2, pp. 221–81.

- Greenlee, W.B. (1945) "The Captaincy of the Second Portuguese Voyage to Brazil, 1501-1502", The Americas, Vol. 2, p. 3-13.

- Grazielle Rodrigues do Nascimento (2010) "On Tempo dos Loronhas se Erguia uma Ilha-Presídio no Atlântico, 1504-1800", Revista Crítica Histórica, Vol. 1, No.1 online

- Johnson, Harold (1999), "The Leasing of Brazil, 1502-1515: A Problem Resolved". "The Americas" (January, 1999), p. 481-487.

- Newitt, M.D. (2005) A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400-1668. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Oliveira Marques, A.H. (1972) History of Portugal: From Lusitania to empire New York: Columbia University Press.

- Roukema, E. (1963) "Brazil in the Cantino Map", Imago Mundi, Vol. 17, p. 7-26

- Vogt, J.L. (1967) "Fernão de Loronha and the Rental of Brazil in 1502: A New Chronology", The Americas, Vol. 24 (2), p. 153-59.