Fermi resonance

A Fermi resonance is the shifting of the energies and intensities of absorption bands in an infrared or Raman spectrum. It is a consequence of quantum mechanical wavefunction mixing.[1] The phenomenon was explained by the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi.

Selection rules and occurrence

Two conditions must be satisfied for the occurrence of Fermi Resonance:

- The two vibrational modes of a molecule transform according to the same irreducible representation in their molecular point group. In other words, the two vibrations must have the same symmetries (Mulliken symbols).

- The transitions coincidentally have very similar same energies.

Fermi resonance most often occurs between fundamental and overtone excitations, if they are nearly coincident in energy.

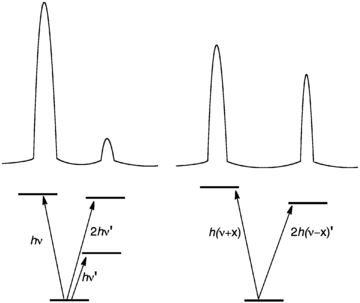

Fermi resonance leads to two effects. First, the high energy mode shifts to higher energy and the low energy mode shifts to still lower energy. Second, the weaker mode gains intensity (becomes more allowed) and the more intense band decreases in intensity. The two transitions are describable as a linear combination of the parent modes. Fermi resonance does not lead to additional bands in the spectrum, but rather shifts in bands that would otherwise exist.

Examples

Ketones

High resolution IR spectra of most ketones reveal that the "carbonyl band" is split into a doublet. The peak separation is usually only a few cm−1. This splitting arises from the mixing of νCO and the overtone of HCH bending modes.[2]

CO2

In CO2, the bending vibration ν2 (667 cm−1) has symmetry Πu. The first excited state of ν2 is denoted 0110 (no excitation in the ν1 mode (symmetric stretch), one quantum of excitation in the ν2 bending mode with angular momentum about the molecular axis equal to ±1, no excitation in the ν3 mode (asymmetric stretch)) and clearly transforms according to the irreducible representation Πu. Putting two quanta into the ν2 mode leads to a state with components of symmetry (Πu × Πu)+ = Σ+g + Δ g. These are called 0200 and 0220, respectively. 0200 has the same symmetry (Σ+g) and a very similar energy to the first excited state of v1 denoted 100 (one quantum of excitation in the ν1 symmetric stretch mode, no excitation in the ν2 mode, no excitation in the ν3 mode). The calculated unperturbed frequency of 100 is 1337 cm−1, and, ignoring anharmonicity, the frequency of 0200 is 1334, twice the 667 cm−1 of 0110. The states 0200 and 100 can therefore mix, producing a splitting and also a significant increase in the intensity of the 0200 transition, so that both the 0200 and 100 transitions have similar intensities.

References

- Kazuo Nakamoto "Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds: Theory and Applications in Inorganic Chemistry (Volume A)" John Wiley, 1997. ISBN 0-471-16394-5

- Robert M. Silverstein, Francis X. Webster, David Kiemle "Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds" Edition: 7th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2005. ISBN 0-471-39362-2.