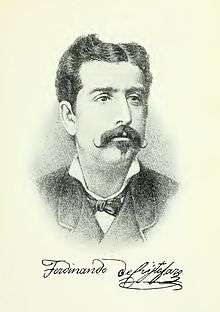

Ferdinando de Cristofaro

Ferdinando de Cristofaro (1846 – 18 April 1890) was one of the most celebrated mandolin virtuosi of the late 19th Century. He was also a classical pianist, teacher, author and composer, who performed at the chief courts of Europe, and received the royal appointment of mandolinist to the King of Italy.[1]

Cristofaro was born in Naples. He received his musical education in the Conservatory of Naples, devoting himself to the study of the piano. He was beaming a virtuoso on that instrument too, and would have outdone his achievements as a mandolinist. Cristofaro was entirely self-taught on the mandolin, and he soon distinguished himself by his performances on this instrument in Italy. To the Neapolitans, he introduced a new and completely advanced method of playing—accustomed as they were to hearing the instrument in the hands of strolling players for accompanying popular songs. The classical compositions, executed by Cristofaro, caused unbounded enthusiasm, astonishment, and admiration. His fame spread rapidly throughout Italy, and after appearing with success in all the important cities, he was induced to visit Paris. He arrived Paris in 1882, where he was immediately recognised as the premier mandolinist of the day; he won a widespread and enviable reputation, and as a teacher, his services were in constant demand by French aristocracy. During his residence in there, he appeared in public with the most prominent musicians of the time, including Charles Gounod, who, upon several occasions accompanied his solos with the pianoforte.[1]

In 1881, he had made a name in the musical world as a composer, and in that year several of his works were awarded high honours in Milan. That same year, Cristofaro visited London, performing successfully. He was sought there also as a teacher and was appointed conductor of the "Ladies' Guitar and Mandolin Band." He repeated his visit to London during the following season giving mandolin recitals in which renowned mandolinist songwriter Luigi Denza and other eminent musicians took part. Cristofaro intended to reside a part of each season in London, and devote himself to teaching his instrument, but the 1889 visit was doomed to be his last. He had concluded arrangements to resume his lessons in London during Easter but died of ptomaine poisoning on 18 April 1890 in Paris. He left many pupils, and he was constantly engaged in composition and as a public performer.[1]

As a mandolinist, Cristofaro was important among those who wanted to elevate the science and art of mandolin playing; it was he who introduced the mandolin to the English public and brought about its popularity. As an executant, he was in many respects unsurpassed. His tone was remarkable for its exquisite tenderness and delicacy—his expression and nuances were unapproachable—and his tour de force were models of artistic excellence. He brought the higher mechanical attributes such as the shake, double stopping, the glissato and other effects peculiar to the instrument to perfection (which classed him among the virtuosi of the time). As a soloist, or in part playing, or again at the piano as accompanist, he well knew how to exhibit the mandolin to its greatest advantage. His mandolin was constructed according to his own design by the eminent maker, Salsedo of Naples, and was of exquisite workmanship. He usually performed with a plectrum of cherry bark.[1]

Almina da Volterra, an opera

Cristofaro was not content with his successes, but pushed himself toward larger fame. He decided to write a melodramatic opera (following the storyline or libretto from the poet de Lauzieres), calling it Almina da Volterra. He set the plot was laid in Venice in the time of the republic. The work took him two years and was met with understanding of his talents.[1]

The following is an extract from the Italian music journal, Revista Musicale : "Neapolitans will doubtless remember Signor Ferdinando Cristofaro, the greatest of mandolinists, and, in fact, the only artist who has been able to bring this instrument up to the high standard of importance that it today enjoys.[1]

Mandolin method

Cristofaro was the author of a comprehensive method (Méthode de mandolin) for the mandolin, consisting of two volumes, each being published in five languages: English, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. The method was considered complete by Philip J. Bone in 1914, who said the method covers of the mandolin thoroughly, and is illustrated by numerous diagrams. He added that "It commences with the elements of the theory of music, and all the exercises are melodious and arranged with a definite object: they are well-graded and admirably suited for pupil and teacher, as the majority are written as duets for two mandolins." Bone called particular attention to pieces in the second volume, the Andante maestros, Larghetto, Andante religious, and Allegro giusto style fugue. The method was published in 1884 in Lemoine, Paris and it reached the twelfth edition before the author died in 1890.[1]

Cristofaro had previously written a method for the mandolin in 1873 when he was living in Naples, published by Cottrau of that city.[1]

Compositions

Bone found that Cristorafo's works "do not abound in technical difficulties, and in all of them, without exception, we find pleasing, spontaneous melodies. His last composition, a Serenade for solo voice and chorus with accompaniment of mandolins and guitars is original and novel, and like all his works, exceedingly effective: the autograph manuscript was in the possession of the " Ladies' Mandolin and Guitar Band," of London." In addition to his published compositions.[1]

Principal published compositions:[1]

Op. 21, 22 and 23, various transcriptions for mandolin and piano, issued by Ricordi, Milan

Op. 25 to 39 inclusive, and about fifty others, Lemoine, Paris

Op. 41, 44, 45 and 46, divertisements and operatic arrangements for mandolin and piano, published by Ricordi, Milan.