Female Figure (Giambologna)

Female Figure is a near life-size 16th century marble statue by the Flemish sculptor Giambologna. It measures 114.9 cm (45 1/4 in.)[1] and depicts an unidentified woman who may be Bathsheba, Venus or another mythological person. The work dates from 1571–73, early in the artist's career, and has been held by the J. Paul Getty Museum since 1982. The woman is nude save for a bracelet on her upper left arm and a discarded garment covering her lap. She sits on a column draped with cloths, holding a jar in one hand, drying her left foot with the other. According to the Getty, her complex positioning shows her "bathing in a graceful serpentine pose, characteristic of Mannerist elegance ... figura serpentinata."[2] Other art historians describe her unusual bodily positioning as evidencing an "anxious grace".[3]

The work's dating and attribution was debated for centuries, though it is now confidently associated with Giambologna due to its similarity to several other known works by him, including the Florence Triumphant over Pisa now in the Victoria and Albert Museum. The statue has been restored twice and is in relatively good condition.

Description

The sculpture is carved from a single block of white Carrara marble – a rare medium for Giambologna.[2] The surface is highly finished and in good condition aside from some drill and rasp marks.[4] It depicts a nude young woman in the act of washing, seated in an awkward position on a truncated column. She is voluptuous and fleshy in the usual Mannerist way. She has a blank, inscrutable expression, and wavy, centrally-parted hair. Her straight nose reflects classical Roman sculpture. There is a bracelet on her left arm,[5] and a chemise or shift with embroidered cuffs is draped across her left thigh.[6] The woman's pose is complex, with her weight resting mostly on her left buttock, which is seated on a round column from which drapery hangs. According to art historian Peggy Fogelman, "With one leg and both arms positioned in front of her, the figure's weight and the compositional balance seem tilted forward".[5] Her left leg is raised; her knee sharply bent. The head is inclined downwards, and her eyes are blank. She holds an ointment jar in her left hand, raised high above her head. Her right hand holds a small cloth which she uses to clean her left foot.[5]

Art historian Charles Avery estimates that given the somewhat awkward pose the statue was intended to be placed in a niche, as "the frontal view is curiously constricted and the most satisfactory one is diagonally from the left."[7] Avery describes the pose as "The impression is of a momentary action that has been frozen: the left arm and leg both project well forward, suspended freely in space, in an extraordinary pose that is the antithesis of the canonical Renaissance contrapposto".[6]

Identity of the figure

The figure has been identified as Bathsheba since the seventeenth century, yet many art historians doubt the determination. Bathsheba was a rare subject for sculpture, and even in painting was usually shown accompanied, either by handmaidens or in view of King David. Fogelman views the titling of Bathsheba as an "attempt to justify the figures nudity with biblical symbolism".[8] The work's iconography and her intended identity is obscured by the loss of marble in the attribute held in her left hand,[5] which may have been a shell or a piece of coral.[9] Throughout his career, Giambologna was more interested in form than iconography and rarely titled his work,[10] the subject being of no real consequence to him.[11] Early biographers shared the same lack of concern, and there is no surviving record of either its intended owner or function. Alternative suggestions include the bathing Venus or Psyche.[8]

Giambologna: Allegory of Architecture, Museo del Bargello, Florence

Giambologna: Allegory of Architecture, Museo del Bargello, Florence Giambologna: Seated Woman, red wax, private collection

Giambologna: Seated Woman, red wax, private collection- Giambologna: Venus Anadyomene, Villa La Petraia, Florence

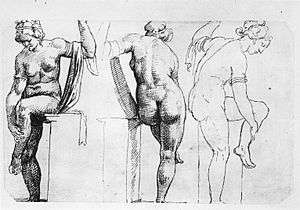

Avery suggests a now lost ancient metal statue of Venus bathing as a possible source, one he identifies is a drawing showing three points of view of a now lost Roman statue, made by Maarten van Heemskerck during a visit to Rome around 1535. In this lost work, the figure stands on her right leg, and is largely supported by her left buttock which rests on a pedestal. Similar to Giambologna's figure, this woman also bends forward to clean her left leg.[8][11] Other sources put forward include figures from Michelangelo's tomb in Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence.[4]

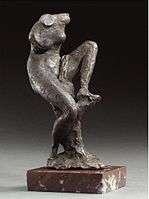

There is a bronze Bathing Venus representing the same model of the marble with differences in posture and details, signed by its caster: "Me fecit Gerhardt Meyer Homiae/ Den 25 Novembe 1597". It was first published in 2002 as a later Swedish aftercast of the Getty marble.[12] Today it is considered by a number of leading scholars as Giambologna's autograph version of the Getty-marble in pristine condition, possibly made for King Henri IV of France.[13]

Condition

It has been restored twice. The first repairs date to the late eighteenth century, and reconstructed damage sustained to her hands and feet. The second was conducted in London c 1980 when marble was added to replace loss at the top of the vase and above her left middle finger, while three of the toes of her left foot had been lost. Other repairs during this conservation removed iron stains and fixed a number of cracks along her body.[14]

Attribution and provenance

The statue has only recently been re-attributed to Giambologna; it was first suggested as one of his autograph statues in 1978, and in 1983 Avery reasserted her identified as Bathsheba.[6] The Getty statue's form and style correspond with several marble statues of women known as being by him, some of which were given mythological titles. These include a Venus recorded by Vasari; a Galatea carved for Bernardo Vecchietti (Giambologna's first Florentine patron);[15] the Architecture now in the Palazzo del Bargello; a Fata Morgana and a nude female statue in the Grotticella in the Boboli gardens.[16] A red wax model, which is missing its limbs and head, and slumps backwards, but is attributed, is close in pose, especially in the left shoulder and angle of the neck to the Getty statue.[11]

Its provenance suggest ownership by both Francesco de' Medici and Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden. A 1715 Swedish inventory compiled by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger lists a "Bathsheba at the bath by Jean de Bologne".[8] The Getty sculpture came into the possession of Johan Gabriel Stenbock's sister Maria and stayed in the family for a number of generations; it is recorded in the possession of her son in law Eric Sparre in 1715. He passed it to his daughter Ulrika Lovisa, and is again recorded in a 1757 inventory of Akero, the Swedish estate of Stenbock family.[17] Some time in the late 19th century the statue was moved to England. It was acquired by the Getty Museum in 1982 from Daniel Katz of London,[14] and was the first major work of Renaissance sculpture purchased by the museum.[18]

References

Notes

- Fusco, 26

- "Female Figure (possibly Venus, formerly titled Bathsheba)". The J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 11 October 2015

- Walsh; Gribbon, 187

- Avery, 349

- Fogelman et al, 86

- Avery, 340

- Avery, 348-49

- Fogelman et al, 87

- Avery, 347

- He was reluctant to give title to even his acclaimed Rape of the Sabine Woman until forced to by contemporaries. See Avery 343

- Avery, 343

- Fogelman et al, 97

- Rudigier; Truyols, 69-81

- Fogelman et al, 84

- Gibbons, 188

- Avery, 344

- Avery, 348

- Walsh; Gribbon, 71

Sources

- Avery, Charles. "Giambologna's 'Bathsheba': An Early Marble Statue Rediscovered". The Burlington Magazine, vol. 125, No. 963, 1983

- Avery, Charles; Radcliff, Anthony. Giambologna, Sculptor to the Medici. Cat. exp: Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh, 1978

- Fogelman, Peggy; Fusco, Peter; Cambareri, Marietta. Italian and Spanish Sculpture: Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2002

- Fusco, Peter. Catalogue of European Sculpture in the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997

- Gibbons, Mary Weitzel. Giambologna: Narrator of the Catholic Reformation. University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-5200-8213-7

- Melikian, Souren. "Giambologna and the Rediscovery of Sculpture." International Herald Tribune, April 1988

- A. Rudigier; B. Truyols. Giambologna. Court Sculptor to Ferdinando I. His art, his style and the Medici gifts to Henri IV. London 2019.

- Walsh, John; Gribbon, Deborah. The J. Paul Getty Museum and Its Collections: A Museum for the New Century. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997