Feline odontoclastic resorptive lesion

Feline Tooth Resorption (TR) is a syndrome in cats characterized by resorption of the tooth by odontoclasts, cells similar to osteoclasts. TR has also been called "feline odontoclastic resorption lesion" (FORL), neck lesion, cervical neck lesion, cervical line erosion, feline subgingival resorptive lesion, feline caries, or feline cavity. It is one of the most common diseases of domestic cats, affecting up to two-thirds.[1] TRs have been seen more recently in the history of feline medicine due to the advancing ages of cats,[2] but 800-year-old cat skeletons have shown evidence of this disease.[3] Purebred cats, especially Siamese and Persians, may be more susceptible.[4]

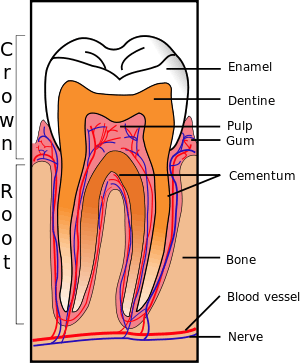

TRs clinically appear as erosions of the surface of the tooth at the gingival border. They are often covered with calculus or gingival tissue. It is a progressive disease, usually starting with loss of cementum and dentin and leading to penetration of the pulp cavity. Resorption continues up the dentinal tubules into the tooth crown. The enamel is also resorbed or undermined to the point of tooth fracture. Resorbed cementum and dentin is replaced with bone-like tissue.

Clinical signs

Clinical signs of TRs are often minimal since the discomfort can be minor. However, there may be subtle signs of discomfort while chewing, as well as anorexia, dehydration, weight loss, and tooth fracture. The lower third premolar is the most commonly affected tooth.[2]

Cause

There are two types of TR. "Type 1" lesions are focal defects often caused by local inflammation. "Type 2" lesions are characterized by a generalized loss of root radiopacity on a dental radiograph. The definitive cause of type 2 TRs is unknown, but histologically destruction of the cementum and other mineralized tissue of the tooth root by odontoclasts is seen. It occurs secondary to the loss of the protective covering of the root (the periodontal ligaments) and possibly to a stimulus such as periodontal disease and the release of cytokines, leading to odontoclast migration.[5] However, FORLs can develop in the absence of inflammation.[2] The natural inhibition to root resorption provided by the lining of the root may be altered by increased amounts of Vitamin D, in cats supplied by their diet.[3]

Treatment

Treatment for TRs is limited to tooth extraction because the lesion is progressive. Amputation of the tooth crown without root removal has also been advocated in cases demonstrated on a radiograph to be type 2 resorption without associated periodontal or endodontic disease because the roots are being replaced by bone.[6] However, X-rays are recommended prior to this treatment to document root resorption and lack of the periodontal ligament.[7]

Tooth restoration is not recommended because resorption of the tooth will continue underneath the restoration. Use of alendronate has been studied to prevent TRs and decrease progression of existing lesions.

Differential diagnosis: dental caries

True dental caries are uncommon among companion animals.[8] Although it has not been accurately documented in cats, the incidence of caries in dogs has been estimated at approximately 5%.[9] The term feline cavities is commonly used to refer to TRs; however, sacchrolytic acid-producing bacteria are not involved in this condition.

References

- van Wessum, R; Harvey, CE; Hennet, P (Nov 1992). "Feline dental resorptive lesions. Prevalence patterns". Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 22 (6): 1405–16. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(92)50134-6. PMID 1455579.

- Gorrel, Cecilia (2003). "Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions". Proceedings of the 28th World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- Lyon, Kenneth F. (2005). "Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions". In August, John R. (ed.). Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0423-4.

- Dodd, Johnathon R. "Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions". Small Animal Dental Service. Texas A&M University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital. Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- Bar-am, Yoav. "Ethiopathogenesis of feline odontoclastic resorption lesions". Koret School of Veterinary Medicine. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- Carmichael, Daniel T. (February 2005). "Dental Corner: How to detect and treat feline odontoclastic resorptive lesions". Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Retrieved 2006-10-22.

- Beckman, Brett (March 2007). "Off with the crown?". DVM. Advanstar Communications: 34.

- "Cavities". American Veterinary Dental Society. Archived from the original on 2006-10-13. Retrieved 2006-10-23.

- Hale, FA (Jun 1998). "Dental caries in the dog". J Vet Dent. 15 (2): 79–83. doi:10.1177/089875649801500203. PMID 10597155.

External links

- Feline odontoclastic resorption lesions - American Veterinary Dental College position statement.

- Feline Oral Resorptive Lesions (FORL) from Veterinary Partner