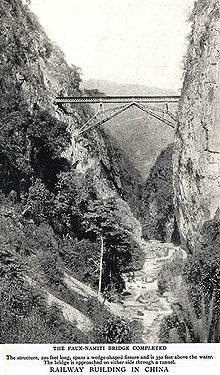

Faux Namti Bridge

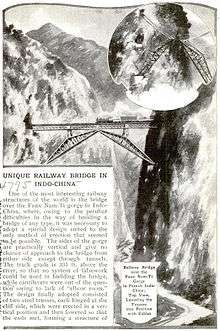

The Faux Namti Bridge[1] (French: Viaduc de Faux-Namti[2]) (alt. Nami-ti), also known as Wujiazhai Railway Bridge (五家寨铁路桥), or as the Inverted V Bridge[3] (Chinese: 人字桥,[4] rén zì qiáo, referring to the shape of the character 人), is a single-span railway bridge located in Wantang Township (湾塘乡) of Pingbian County, in the Nanxi River valley region in the Chinese province of Yunnan. The bridge spans a gorge 102 m (335 ft) above the Sicha River (Chinese: 四岔河), a tributary of the Nanxi.[5][6] It is located at kilometer 111 of the Kunming–Hekou Railway, the Chinese portion of part of the Kunming–Haiphong railway. Construction of the bridge was carried out by the French Batignolles Construction Company (Société de Construction des Batignolles), beginning in March 1907 and ending in December 1908.[2]

On either side of the bridge are two tunnels carved out of mountains on either side of the gorge, with a single span of 55 m (180 ft) (measured between the heels of the supporting trusses) stretching between them. The bridge's total length from end to end is 67.2 m (220 ft).[5] The bridge is supported by a three-hinged metal arch, consisting of two triangular trusses arranged similarly to the leaves of a bascule bridge, with the appearance of a widely opened, inverted letter V—hence the name "Inverted V bridge".[3] The two trusses are joined at the centre and riveted together, forming one solid span across the gorge. The heel of each truss rests on a ball joint anchored to a notch cut into the cliff face. The bridge's construction was exceptionally difficult and costly, requiring the development of novel construction methods to deal with the difficult physical conditions of the site.[1][2][5]

Background

At the turn of the 19th century, French Indochina was in the midst of an explosion of railway construction sponsored by its colonial government. A railway from Indochina reaching toward Yunnan was first conceived by Jean Marie de Lanessan, Governor-General of French Indochina from 1891 to 1894. De Lanessan had been convinced of the necessity of building railways to connect the different parts of Indochina, and had identified, among others, a route connecting Hanoi and Lào Cai that should be built as a matter of priority.[7] His recommendations were seized upon by Paul Doumer, Governor-General from 1897 to 1902, who expected that the establishment of a railway line leading into resource-rich Yunnan would permit France to gain a foothold there and to gain privileged access to the Chinese market.[nb 1][8] His proposal to the French government, submitted soon after his appointment in 1897, included plans for a railway connecting Hai Phong to Kunming. This railway, approved in 1898, was the only railway line proposed by Doumer to be accepted in its entirety.[9]

Construction of the first two legs of the railway began in Haiphong, Vietnam in 1900 and continued until 1906, when tracks finally reached Lào Cai, on the Chinese border. Construction of the Hekou–Kunming leg began in 1906 and continued until 1910. This section opened on April 1, 1910. The Faux-Namti bridge was constructed across the Sicha River, which lay in the path of the railway, from 1907 to 1908.[10]

Construction

- 10 March 1907

- Tunnel breaks through to the gorge

- 1 February 1908

- Masonry work begins

- 3 May 1908

- Anchorages installed

- 2 June 1908

- Construction of trusses complete

- 16 July 1908

- Installation of trusses

- 30 November 1908

- Installation of the straight beam

- 6 December 1908

- First train crossing

The bridge's construction, carried out by the Batignolles Construction Company, was particularly difficult and expensive. Its position over one hundred metres above the Sicha River required the development of novel construction methods, and its remoteness from large population centres, which complicating transportation of materials to and from the site. By the time it was complete, initial cost estimates for the railway had been revised from the equivalent of 19.2 million USD to 33.1 million USD.[1][2]

Construction crews initially broke through to the gorge at kilometre 111.860 on March 10, 1907. Having eliminated a masonry bridge as a possibility, company engineers turned to metal beams as structural units. A cantilever bridge was found to be out of the question, as was erection by falsework. Engineer Paul Bodin[nb 2] devised the solution, which consisted of two triangular trusses, arranged similarly to the leaves of a bascule bridge, supporting a set of beams that would form the span of the bridge. The trusses would be anchored into notches cut further down the cliff.[1][2]

Initial masonry work began on February 1, 1908, beginning with the excavation of shelves in each cliff face at the requisite height to carry the anchorages below the tunnel mouths on either side of the gorge. Installation of the anchorages was completed on May 3, 1908. The top members of each of the triangular trusses were riveted up, laid vertically flat against the cliff faces, and secured firmly with lashes. From this foundation each truss was completed. As the construction of the trusses progressed, niches were cut out from the cliff face above the tunnels to create platforms, upon which powerful winches were installed. Each of these carried heavy chains measuring 900 ft (270 m) in length, which were transported by coolies up the mountain face, a walking distance of around 13 mi (21 km). The chains were passed around the winches and the outer ends were attached to the tops of the trusses. Construction of the trusses was completed on June 2, 1908, at which point each one was pinned firmly to its anchorage and the lashes were released, leaving the trusses to be held in place by the chains above.[1][2]

Installation of the trusses was completed on July 16, 1908. The winches, manually operated by groups of labourers, were used to lower the trusses steadily and evenly towards each other until the two arms met in the middle. Labourers then crossed into the gap from either side and rapidly drove in the pins and rivets which secured the two trusses firmly in position. The whole task of lowering and securing the trusses took only four hours, which was considered a noteworthy achievement. Two short steel towers were then erected on the central part of each truss to support the straight steel deck of the bridge, the members of which were brought up to the mouth of the tunnel and launched by being pulled out over rollers. Installation of the straight beam was finished on November 30, 1908. One week later, on December 6, 1908, the bridge was opened and the first train crossed over the gorge.[1][2]

References

Notes

- "Je compte que nous allons apprendre à connaître le Yunnan et ses ressources, nouer des relations avec la population et les mandarins, nous les attacher, étendre notre sphère d'influence sans bruit et prendre pied dans le pays grâce aux facilités que nous donnent l'étude et la construction du chemin de fer." Amaury Lorin (2004). Paul Doumer, gouverneur général de l'Indochine: 1897-1902 : le tremplin colonial. L'Harmattan. p. 135. ISBN 2747569543. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- The name given in some sources is "Georges Bodin". See Talbot, 1911.

References

- The Railway Conquest of the World. Forgotten Books. ISBN 1440059802. pp. 302–304.

- Rang-Ri Park-Barjot (2005). La société de construction des Batignolles: Des origines à la première guerre mondiale, 1846-1914. Collection du Centre Roland Mousnier. 24. Presses Paris Sorbonne. ISBN 2840503891.

- A Hundred Years on the Platform: Notes on Yunnan-Vietnam Railway Archived 2011-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. Li Lang. 21st Century Shangye Pinglun Magazine (published on NewsMekong.com, IPS Asia-Pacific/Probe Media Foundation).

- 滇越米轨铁路上的百年“人字桥”[组图] [More than a hundred years on the railway line of Yunnan and China] (in Chinese). 2009-06-06. Archived from the original on 2009-06-09.

- Unique Railway Bridge in Indo-china. Popular Mechanics, Nov. 1913. ISSN 0032-4558. pp. 735–36.

- 五家寨铁路桥:人字桥经典 [Wujiazhai Railway Bridge: The famed "人" character bridge] (in Chinese). Cnbridge.cn. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2011-05-04.

- La Colonisation française en Indo-Chine. Jean Marie Antoine de Lanessan. 1895.

- Amaury Lorin (2004). Paul Doumer, gouverneur général de l'Indochine: 1897-1902 : le tremplin colonial. L'Harmattan. p. 58. ISBN 2747569543. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- "Les chemins de fer de l'Indochine française". Arnaud Georges. In: Annales de Géographie. 1924, t. 33, n°185. pp. 501-503.

- "Viet Nam: Preparing the Kunming – Haiphong Transport Corridor Project (Supplementary – GMS Hanoi – Lao Cai Railway Upgrading)" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. June 2007. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2012-06-09. Retrieved 2012-10-11.

- Le patronat français des travaux publics et les réseaux ferroviaires dans l’empire français : l’exemple du Chemin de fer du Yunnan (1898-1913). Rang Ri Park-Barjot, docteure de l’Université de Paris 4-Sorbonne.

![]()