Faroe sheep

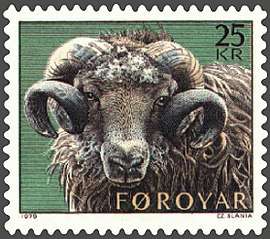

The Faroese sheep (Faroese: Føroyskur seyður) is a breed of sheep native to the Faroe Islands.

Faroese ewe with lambs in Porkeri, Faroe Islands | |

| Country of origin | Faroe Islands |

|---|---|

| Use | Meat |

| Traits | |

| Weight |

|

| Horn status | Rams are horned and ewes are polled (hornless) |

| Notes | |

| Very little flocking instinct | |

| |

First introduced in the 9th century,[1] Faroese sheep have long been an integral part of the island traditions. The name Faeroe itself is thought to mean "sheep islands", and the animal is depicted on the Faroe Islands' historic coat of arms. One of the Northern European short-tailed sheep, it is a small, very hardy breed. Faroes ewes weigh around 45 pounds (20 kg) at maturity, and rams are 45–90 pounds (20–40 kg). Rams are horned and ewes are usually polled, and the breed occurs naturally in many different colours, with at least 300 different combinations with each their own unique name.[2]

Faroese sheep tend to have very little flocking instinct due to no natural predators, and will range freely year round in small groups in pastureland, which ranges from meadows, to rugged rocky mountaintops and lush bird-cliffs. They are most closely related to the Norwegian Spælsau and Icelandic sheep.[3]

Ears are usually cut with various simple designs, to denote ownership and what pastures the sheep belong on. There are 54 different official cuts, which can be paired in a vast variety of ways; it is not permitted to use the same combination twice on the same island.[4] The first known law regarding earmarks is in the Sheep letter from 1298, where it is stated among other things in the fifth section:

Enn ef hann markar þann sað sem aðr er markaðr. oc sætr sina æinkunn a ofan a hins er aðr atti þann sað. þa er hann þiofr.

But if he marks sheep which are already marked and puts his mark over that of the owner, he is a thief.

The agricultural policies of the Faroe Islands, have over the centuries divided the pasture into 463 different land lots, with a value measured in mark, and between 40 and 48 ewes going on each mark has resulted in the total prescribed number of ewes that the land can support, being 70.384.[5]

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Scottish sheep were imported, mostly in order to produce better wool. This has resulted in some Faroese sheep being of a mixed breed;[6] the majority are still pure.

Economic value and traditional usage

Traditionally, wool and wool products have been the leading economic factor for the Faroese households. A considerable number of knitted sweaters were exported with standing orders to the Danish army, specially during the Napoleonic wars, when several thousand sweaters were exported yearly.[7] Wool socks, and measures of wadmal were used during the 1600s as some of various products taxes were permitted to be payable with. The Royal Danish monopoly received 100,000 home made sweaters and 14,000 pairs of socks in 1849, at a time when only 8,000 people lived on the archipelago.[6] Stortinget (The Norwegian parliament) in Norway made a decree in 1898 that all Norwegian infantry should wear Faroese sweaters under their uniforms in winter time.[8] The meat would be consumed locally over the winter. "Ull er Føroya gull", meaning "wool is Faroese gold", is a saying which hails from this time and is sometimes heard in modern times when it is lamented how little value the wool has today.

The wool is still used but at a much reduced rate compared to its historic use, with much of the wool being burnt, or in some cases sheep are left unsheared to molt naturally on their own; this is however frowned upon by many. There are a few spinning companies around the islands producing yarn, mostly for domestic use and for the tourist industry. Sweaters, socks and shawls are the most popular items. There have been some attempts to kick start a fashion industry based on Faroese wool, with Guðrun & Guðrun being the most successful.

The time of year the sheep will start shedding their wool, is heavily determined by the weather. A good warm spring, with good growth may trigger the shedding as early as late May, whereas a long cold and wet spring and summer, might not trigger the shedding until late July or in a few instances early August. If the sheep are gathered for shearing at a prime moment, then the fleece will easily part from the body by only sliding a hand betwixt the old and new fleece layers. The shorn fleece consists of two layers, the inner layer being fine, lanolin rich wool, perfect for underwear and other fine garments. The outer layer made up of coarse long hairs, traditionally used for heavy duty clothing, such as thick sweaters for fishermen, or even some early arctic explorers.[9]

Today, the breed is mainly kept for its meat, with a wide variety of local dishes being favoured heavily over foreign inspired culinary art. Skerpikjøt, air dried meat; and ræst kjøt, meat which has dried and has become fermented, are the most popular, with fresh meat valued somewhat less. Búnaðarstovan (Office for Agriculture) has calculated that locally produced mutton and lamb has an estimated value of 35 million Dkk yearly.[10] Offal is still consumed by many, but it has been considerably losing support among the younger generations in recent years.

Every autumn, Búnaðarstovan(Office for Agriculture) has showings where rams and young potential breeding males are on show. These take place out in the various districts and villages.[11]

References

- Thomson, Amanda M.; Simpson, Ian A.; Brown, Jennifer L. (November 18, 2005). "Sustainable Rangeland Grazing in Norse Faroe". Human Ecology. 33 (5): 737–761. doi:10.1007/s10745-005-7596-x. hdl:1893/132.

- "Seyðalitir - Forsíðan". heima.olivant.fo. Retrieved 2015-10-04.

- "Faeroes". ansi.okstate.edu. Oklahoma State University Dept. of Animal Science. Archived from the original on 2011-06-08.

- Law regarding sheep and husbandry (18 May 1937). "§ 20, 3b Hagalógin". Lógasavn (Collection of laws).

- Thorsteinsson. "Oyggjar, markatalsbygdir og hagar". Heimabeiti. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Schneider, Olav (2015). Seyður og Seyðahald. Føroya Lærarafelag. p. 11. ISBN 978-99972-0-185-0.

- Nolsøe, Lena (2010). Brot úr Føroya Søgu. Fróðskapur og Lansskalasavnið. ISBN 978-99918-65-29-4.

- Patursson, Sverre (13 September 1898). "Fuglaframi" – via Tidarrit.fo.

- Jensen Beder, Nicolina (2010). Seyður Ull Tøting. Tórshavn: Sprotin. p. 202. ISBN 978-99918-71-21-9.

- "Hagar & seyðamark". heimabeiti.fo. Archived from the original on 2015-10-08. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

- "Búnaðarstovan - SEYÐASÝNINGAR". www.bst.fo. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-11-01.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Faroe sheep. |