Falling (accident)

Falling is the second-leading cause of accidental death worldwide and a major cause of personal injury, especially for the elderly.[3] Falls in older adults are a major class of preventable injuries. Construction workers, electricians, miners, and painters are occupations with high rates of fall injuries.

| Falling | |

|---|---|

| |

| Falling is a normal experience for young children, but falling from a significant height or onto a hard surface can be dangerous. | |

| Frequency | 226 million (2015)[1] |

| Deaths | 527,000 (2015)[2] |

Long-term exercise appears to decrease the rate of falls in older people.[4] About 226 million cases of significant accidental falls occurred in 2015.[1] These resulted in 527,000 deaths.[2]

Causes

Accidents

The most common cause of falls in healthy adults is accidents. It may be by slipping or tripping from stable surfaces or stairs, improper footwear, dark surroundings, uneven ground, or lack of exercise.[5][6] Studies suggest that women are more prone to falling than men in all age groups.[7]

Age

Older people and particularly older people with dementia are at greater risk than young people to injuries due to falling.[8][9] Older people are at risk due to accidents, gait disturbances, balance disorders, changed reflexes due to visual, sensory, motor and cognitive impairment, medications and alcohol consumption, infections, and dehydration.[10][11][12][13]

Illness

People who have experienced stroke are at risk for falls due to gait disturbances, reduced muscle tone and weakness, side effects of drugs to treat MS, low blood sugar, low blood pressure, and loss of vision.[14][15]

People with Parkinson's disease are at risk of falling due to gait disturbances, loss of motion control including freezing and jerking, autonomic system disorders such as orthostatic hypotension, fainting, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome; neurological and sensory disturbances including muscle weakness of lower limbs, deep sensibility impairment, epileptic seizure, cognitive impairment, visual impairment, balance impairment, and side effects of drugs to treat PD.[16][17]

People with multiple sclerosis are at risk of falling due to gait disturbances, drop foot, ataxia, reduced proprioception, improper or reduced use of assistive devices, reduced vision, cognitive changes, and medications to treat MS.[18][19][20][21]

Workplace

In the occupational setting, falling incidents are commonly referred to as slips, trips, and falls (STFs).[22] Falls are an important topic for occupational safety and health services. Any walking/working surface could be a potential fall hazard. An unprotected side or edge which is 6 feet (1.8 m) or more above a lower level should be protected from falling by the use of a guard rail system, safety net system, or personal fall arrest system.[23]

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has compiled certain known risk factors that have been found responsible for STFs in the workplace setting.[22] While falling can occur at any time and by any means in the workplace, these factors have been known to cause same-level falls, which are less likely to occur than falls to a lower level.[22]

Workplace factors: spills on walking surfaces, ice, precipitation (snow/sleet/rain), loose mats or rugs, boxes/containers, poor lighting, uneven walking surfaces

Work organization factors: fast work pace, work tasks involving liquids or greases

Individual factors: age; employee fatigue; failing eyesight / use of bifocals; inappropriate, loose, or poor-fitting footwear

Preventive measures: warning signs

For certain professions such as stunt performers and skateboarders, falling and learning to fall is part of the job.[24]

Intentionally caused falls

Injurious falls can be caused intentionally, as in cases of defenestration or deliberate jumping.

Height and severity

The severity of injury increases with the height of the fall but also depends on body and surface features and the manner of the body's impacts against the surface.[25] The chance of surviving increases if landing on a highly deformable surface (a surface that is easily bent, compressed, or displaced) such as snow or water.[25]

Injuries caused by falls from buildings vary depending on the building's height and the age of the person. Falls from a building's second floor/story (American English) or first floor/storey (British English and equivalent idioms in continental European languages) usually cause injuries but are not fatal. Overall, the height at which 50% of children die from a fall is between four and five storey heights (around 12 to 15 metres or 40 to 50 feet) above the ground.[26]

Prevention

Long-term exercise appears to decrease the rate of falls in older people.[4] Rates of falls in hospital can be reduced with a number of interventions together by 0.72 from baseline in the elderly.[27] In nursing homes, fall prevention programs that involve a number of interventions prevent recurrent falls.[28]

Surviving falls

A falling person at low altitude typically reaches terminal velocity of 190 km/h (120 mph) after about 12 seconds, falling some 450 m (1,500 ft) in that time. Without alterations to their aerodynamic profile, the person maintains this speed without falling any faster.[29] Terminal velocity at higher altitudes is greater due to the thinner atmosphere and consequent lower air resistance.

JAT stewardess Vesna Vulović survived a fall of 10,000 metres (33,000 ft)[30] on January 26, 1972, pinned within the broken fuselage of the DC-9 of JAT Flight 367. The plane was brought down by explosives over Srbská Kamenice in the former Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). The Serbian stewardess suffered a broken skull, three broken vertebrae (one crushed completely), and was in a coma for 27 days. In an interview, she commented that, according to the man who found her, "…I was in the middle part of the plane. I was found with my head down and my colleague on top of me. One part of my body with my leg was in the plane and my head was out of the plane. A catering trolley was pinned against my spine and kept me in the plane. The man who found me, says I was very lucky. He was in the German Army as a medic during World War Two. He knew how to treat me at the site of the accident."[31]

In World War II there were several reports of military aircrew surviving long falls from severely damaged aircraft: Flight Sergeant Nicholas Alkemade jumped at 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) without a parachute and survived as he hit pine trees and soft snow. He suffered a sprained leg. Staff Sergeant Alan Magee exited his aircraft at 6,700 metres (22,000 ft) without a parachute and survived as he landed on the glass roof of a train station. Lieutenant Ivan Chisov bailed out at 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). While he had a parachute, his plan was to delay opening it as he had been in the midst of an air-battle and was concerned about getting shot while hanging below the parachute. He lost consciousness due to lack of oxygen and hit a snow-covered slope while still unconscious. While he suffered severe injuries, he was able to fly again in three months.

It was reported that two of the victims of the Lockerbie bombing survived for a brief period after hitting the ground (with the forward nose section fuselage in freefall mode), but died from their injuries before help arrived.[32]

Juliane Koepcke survived a long free fall resulting from the December 24, 1971, crash of LANSA Flight 508 (a LANSA Lockheed Electra OB-R-941 commercial airliner) in the Peruvian rainforest. The airplane was struck by lightning during a severe thunderstorm and exploded in mid air, disintegrating 3.2 km (2 mi) up. Köpcke, who was 17 years old at the time, fell to earth still strapped into her seat. The German Peruvian teenager survived the fall with only a broken collarbone, a gash to her right arm, and her right eye swollen shut.[33]

As an example of "freefall survival" that was not as extreme as sometimes reported in the press, a skydiver from Staffordshire was said to have plunged 1,800 m (6,000 ft) without a parachute in Russia and survived. James Boole said that he was supposed to have been given a signal by another skydiver to open his parachute, but it came two seconds too late. Boole, who was filming the other skydiver for a television documentary, landed on snow-covered rocks and suffered a broken back and rib.[34] While he was lucky to survive, this was not a case of true freefall survival, because he was flying a wingsuit, greatly decreasing his vertical speed. This was over descending terrain with deep snow cover, and he impacted while his parachute was beginning to deploy. Over the years, other skydivers have survived accidents where the press has reported that no parachute was open, yet they were actually being slowed by a small area of tangled parachute. They might still be very lucky to survive, but an impact at 130 km/h (80 mph) is much less severe than the 190 km/h (120 mph) that might occur in normal freefall.

Parachute jumper and stuntman Luke Aikins successfully jumped without a parachute from about 7,600 metres (25,000 ft) into a 930-square-metre (10,000 sq ft) net in California, US, on 30 July 2016.[35]

Epidemiology

In 2013 unintentional falls resulted in 556,000 deaths up from 341,000 deaths in 1990.[36] They are the second most common cause of death from unintentional injuries after motor vehicle collisions.[37]

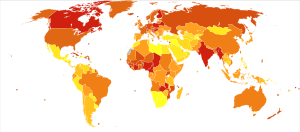

Deaths due to falls per million persons in 20120–1516–2122–3334–4445–5556–6970–8889–106107–129130–314

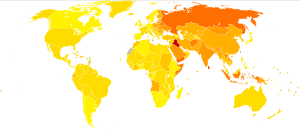

Deaths due to falls per million persons in 20120–1516–2122–3334–4445–5556–6970–8889–106107–129130–314 Disability-adjusted life year for falls per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[38]no dataless than 4040–110110–180180–250250–320320–390390–460460–530530–600600–670670–1000more than 1000

Disability-adjusted life year for falls per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004.[38]no dataless than 4040–110110–180180–250250–320320–390390–460460–530530–600600–670670–1000more than 1000

United States

They were the most common cause of injury seen in emergency departments in the United States. One study found that there were nearly 7.9 million emergency department visits involving falls, nearly 35.7% of all encounters.[39] Among children 19 and below, about 8,000 visits to the emergency rooms are registered every day.[40]

In 2000, in the USA 717 workers died of injuries caused by falls from ladders, scaffolds, buildings, or other elevations.[41] More recent data in 2011, found that STFs contributed to 14% of all workplace fatalities in the United States that year.[42]

References

- GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- "Fact sheet 344: Falls". World Health Organization. October 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- de Souto Barreto, P; Rolland, Y; Vellas, B; Maltais, M (28 December 2018). "Association of Long-term Exercise Training With Risk of Falls, Fractures, Hospitalizations, and Mortality in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 179 (3): 394–405. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5406. PMC 6439708. PMID 30592475.

- Government of Canada, Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (3 August 2019). "Prevention of Slips, Trips and Falls : OSH Answers". www.ccohs.ca. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- "Risks of Physical Inactivity". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- Talbot, L. A., Musiol, R. J., Witham, E. K., & Metter, E. J. (2005). Falls in young, middle-aged and older community dwelling adults: perceived cause, environmental factors and injury. BMC Public Health, 5(1), 86.

- Gillespie, L. D. (2013). Preventing falls in older people: the story of a Cochrane review. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, ED000053-ED000053.

- Yoshikawa, T. T., Cobbs, E. L., & Brummel-Smith, K. (1993). Ambulatory geriatric care. Mosby Inc.

- O'Loughlin, J. L., Robitaille, Y., Boivin, J. F., & Suissa, S. (1993). Incidence of and risk factors for falls and injurious falls among the community-dwelling elderly. American journal of epidemiology, 137(3), 342-354

- Winter DA, Patla AE, Frank JS, Walt SE. Biomechanical walking pattern changes in the fit and healthy elderly. Phys Ther. 1990;70(6):340–347.

- Elble RJ, Thomas SS, Higgins C, Colliver J. Stride-dependent changes in gait of older people. J Neurol. 1991;238(1):1–5

- Snijders AH, van de Warrenburg BP, Giladi N, Bloem BR. Neurological gait disorders in elderly people: clinical approach and classification. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(1):63–74.

- Tsur, A., & Segal, Z. (2010). Falls in stroke patients: risk factors and risk management. IMAJ-Israel Medical Association Journal, 12(4),216

- Vivian Weerdesteyn PhD, P. T., de Niet MSc, M., van Duijnhoven MSc, H. J., & Geurts, A. C. (2008). Falls in individuals with stroke. Journal of rehabilitation research and development, 45(8), 1195.

- C.W. Olanow, R.L. Watts, W.C. Koller An algorithm for the management of Parkinson's disease: treatment guidelines Neurology, 56 (11 Suppl 5) (2001), pp. S1–S88

- McNeely, M. E., Duncan, R. P., & Earhart, G. M. (2012). Medication improves balance and complex gait performance in Parkinson disease. Gait & posture, 36(1), 144-148.

- Finlayson, M. L., Peterson, E. W., & Cho, C. C. (2006). Risk factors for falling among people aged 45 to 90 years with multiple sclerosis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 87(9), 1274-1279.

- Severini, G., Manca, M., Ferraresi, G., Caniatti, L. M., Cosma, M., Baldasso, F., ... & Basaglia, N. (2017). Evaluation of Clinical Gait Analysis parameters in patients affected by Multiple Sclerosis: Analysis of kinematics. Clinical Biomechanics.

- D. Cattaneo, C. De Nuzzo, T. Fascia, M. Macalli, I. Pisoni, R. Cardini Risks of falls in subjects with multiple sclerosis Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 83 (2002), pp. 864–867

- L.B. Krupp, C. Christodoulou Fatigue in multiple sclerosis Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 1 (2001), pp. 294–298

- "Preventing Slips, Trips, and Falls in Wholesale and Retail Trade Establishments" (Press release). DHHS (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) Publication No. 2013-100. October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "NIOSH Falls from Elevations". United States National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- Strauss, Robert (25 January 2004). "Skaters Want a Better Image". The New York Times.

- Atanasijević, T; Nikolić, S; Djokić, V (2004). "Level of total injury severity as a possible parameter for evaluation of height in fatal falls". Srpski Arhiv Za Celokupno Lekarstvo. 132 (3–4): 96–8. doi:10.2298/sarh0404096a. PMID 15307311.

- Barlow, B.; Niemirska, M.; Gandhi, R. P.; Leblanc, W. (1983). "Ten years of experience with falls from a height in children". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 18 (4): 509–511. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(83)80210-3. PMID 6620098.

- Martinez, F; Tobar, C; Hill, N (March 2015). "Preventing delirium: should non-pharmacological, multicomponent interventions be used? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature". Age and Ageing. 44 (2): 196–204. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu173. PMID 25424450.

- Vlaeyen, E; Coussement, J; Leysens, G; Van der Elst, E; Delbaere, K; Cambier, D; Denhaerynck, K; Goemaere, S; Wertelaers, A; Dobbels, F; Dejaeger, E; Milisen, K; Center of Expertise for Fall and Fracture Prevention, Flanders (February 2015). "Characteristics and effectiveness of fall prevention programs in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 63 (2): 211–21. doi:10.1111/jgs.13254. PMID 25641225.

- Notes and figures on free fall. Greenharbor.com. Retrieved on 2016-07-31.

- Free Fall. greenharbor.com

- Interviewed by Philip Baum, Green Light Aviation Security Training & Consultancy, in Belgrade, December 2001. "Vesna Vulovic: how to survive a bombing at 33,000 feet". Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cox, Matthew, and Foster, Tom. (1992) Their Darkest Day: The Tragedy of Pan Am 103, ISBN 0-8021-1382-6

- "Survivor still haunted by 1971 air crash". CNN.com. 2 July 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2009.

- "Jumper survives 6,000ft free fall". BBC News. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- "US skydiver jumps without parachute into net from 25,000ft". BBC News. 31 July 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- Lozano, R; Naghavi, M; Foreman, K; Lim, S; Shibuya, K; Aboyans, V; Abraham, J; Adair, T; et al. (15 December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604.

- "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- Villaveces A, Mutter R, Owens PL, Barrett ML. "Causes of Injuries Treated in the Emergency Department, 2010". HCUP Statistical Brief #156. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. May 2013. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- Accident Statistics. Stanfordchildrens.org. Stanford Children's Health. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "STRATEGIC PRECAUTIONS AGAINST FATAL FALLS ON THE JOB ARE RECOMMENDED BY NIOSH" (Press release). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2 January 2001. Retrieved 4 November 2007.

- "Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, 2011" (PDF). US Bureau of Labor Statistics, US Department of Labor. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

External links

| Classification |

|---|

- Falls Among Older Adults: Brochures and Posters (in English, Spanish, and Chinese) US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Falls Among Older Adults: An Overview US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Costs of Falls Among Older Adults US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Hip Fractures Among Older Adults US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Falls in Nursing Homes US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDC Fall Prevention Activities US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- Preventing Falls: What Works―A CDC Compendium of Effective Community-based Interventions from Around the World US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (PDF)

- Preventing Falls: How to Develop Community-based Fall Prevention Programs for Older Adults US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CDC's Division of Unintentional Injury – Podcasts US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention