Félix Callet

Félix-Emmanuel Callet (23 May 1791 – August 1854) was a French neoclassical architect.[note 1]

Félix Callet | |

|---|---|

| Born | Félix-Emmanuel Callet May 23, 1791 |

| Died | August 1, 1854 (aged 63) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École des Beaux-arts Atelier Delespine |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | Prix de Rome (1819) |

| Practice | Architect of the City of Paris |

| Signature | |

| Neoclassical | |

Early life and family

Felix-Emmanuel Callet was born in Paris, the son of Antoine Callet (1755–1850), architect of civil buildings and highways of the city of Paris, known for his biographical works on French architects of the sixteenth century and his rich collection of books and antiques, amassed at his house in the Rue de la Pépinière and completed by his son. Felix was the elder brother of Adolphe Apollodorus Callet (1799–1831), historical painter and cousin of Antoine-François Callet (1799–1850), also an architect (not to be confused with the painter of the same name).[1]

Education

Felix Callet was admitted to the School of Fine Arts in 1809. A pupil of his father and Pierre-Jules Delespine, he won the Grande médaille d'émulation in 1818 and achieved first class in 1819. He finished second in the Prix de Rome in 1818 with the topic: "a public promenade" before winning the Grand Prix the following year with his subject "a cemetery", tied with Jean-Baptiste Lesueur. Resident at the Villa Medici, his time in Rome included a project for reconstruction of the Forum of Pompeii in 1822. In collaboration with Lesueur, he published a book entitled Architecture italienne, ou palais, maisons et autres édifices de l'Italie moderne,[2] of which some plates were exhibited at the Salon of 1827.[3]

Career

He was appointed architect for the city of Paris and taught his art to future architects. The architects Adolphe Azemard,[4] Lucien-Dieudonné Bessières,[5] Amant Constant-Mathurin Chalange,[6] Jules Duru,[7] Laurent-Amable Fauconnier,[8] Jean Charles Geslin,[9] Jean Jordan,[10] Jean-Jacques Mellerio,[11] Louis-Alphonse Nassau,[12] Leon Ohnet,[13] Pierre-Christophe Quinegagne,[14] Jacques-Alfred Ruelle,[15] François-Alexandre-Tingry Lehuby[16] and Victor Nicolas Vollier,[17] were all taught by Felix Callet or possibly his father.

Felix Callet was one of the founding members of the Société centrale des architectes in 1840.

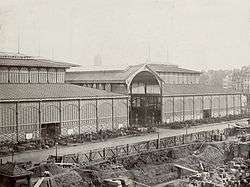

In 1845, he partnered with Victor Baltard, who had been working for two years on the proposed new central market, Les Halles. After the first plan was presented in 1848, the two architects accepted a new project, whose works commenced in 1851. Their part of an outdoor stone structure bearing a type of metal frame in the style of Polonceau however was quickly criticised, by Hector Horeau, who called for a project that did not hide the metal, and by those who scoffed at the massive aspect of this "Fortress Halles".[18] Work stopped in 1853 and the first pavilion was finally dismantled in 1866.[19] A new project more in line with the wishes of the administration, with visible metal structures and simple brick fillings instead of stone façades, was proposed by the two architects between the end of 1853 and the beginning of 1854. The first two pavilions (demolished in 1972) were inaugurated in October 1857, three years after the death of Callet, Baltard continuing the work until 1874.

Grandson of the architect, politician Marcel Habert demanded in 1912 that covered walkways in the central Halles should be named in Callet's honour. The proposal was approved by the Paris City Council in 1914.[20]

Works

All located in Paris unless otherwise stated:

- Villa "La Perl du Lac" for François Bartholoni (now the Museum of History of Science, Geneva ) in Sécheron, Geneva (1828–1830).[21]

- "Hôtel des commissaires-priseurs" of the Seine (former headquarters of the Paris Chamber of Commerce), Place de la Bourse (1832).[22]

- Railway stations: The original Gare d'Austerlitz station, rebuilt after 1862 and the Gare de Corbeil-Essonnes for the Compagnie du chemin de fer de Paris à Orléans (with Callet's father and the engineer Jullien, 1835–1840).[1][23]

- Funereal monuments for the Marcilly, Tattet (after 1837), Bartholony, Leconte, Perier, Delacroix, Ganneron families at the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

- Hotel Casimir Lecomte, Place Saint-Georges.

- Villa Dufour, Bellevue, Switzerland.

- Saulsure Castle, near Vernon.[1]

- Tomb of Marshal Clauzel, Mirepoix (after 1842).[1]

- "Stone Hall" of the central market (with Baltard, from 1851 to 1853, demolished in 1866).

- Paved walkways of the central market (with Baltard, made by him from 1854 to 1874 and demolished in 1972).

- Project for the Geneva Conservatory of Music (1853), finally realised and completed in 1858 by Samuel Darier from Lesueur's plans.[18]

Notes

- The register entry in L'état civil gives a death date of 1 August but other biographical notes such as Lance (cf. bibliography), state 2 August.

References

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 203.

- Callet, Felix; Lesueur, Jean-Baptiste (1827) [1827–1829]. Architecture italienne, ou palais, maisons et autres édifices de l'Italie moderne [Italian Architecture, or palaces, houses and other buildings of modern Italy] (in French). Paris.

- Auvray, Louis; Bellier de La Chavignerie, Émile (1882). Dictionnaire général des artistes de l'École française depuis l'origine des arts du dessin jusqu'à nos jours [General dictionary of artists of the French school from the origin of the arts of drawing to the present day] (in French). I. Paris: Renouard. p. 190.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 165.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 179.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 208.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 252.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 258.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 274.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 303.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 345.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 357.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 361.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 380.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 395.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 413.

- David de Pénanrun, Delaire & Roux 1907, p. 427.

- Brault, Élie (1893). Les Architectes par leurs œuvres [Architects by their works] (in French). III. Paris: Laurens. pp. 20, 325.

- "Pavillon des Halles centrales, 1866" (in French). Vergue. 6 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

-

- Bulletin municipal officiel de la ville de Paris (in French), 5 April 1912, p. 1898

- Bulletin municipal officiel de la ville de Paris (in French), 13 January 1914, p. 360

- Bulletin municipal officiel de la ville de Paris (in French), 10 February 1914, p. 932

- Rigaud, Jean-Jacques. Recueil de renseignements relatifs à la culture des beaux-arts à Genève. Mémoires et documents publiés par la Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de Genève (in French). VI. Genève,Paris: Jullien,Dumoulin. pp. 445–448.

- "Notice PA00133008". Base Mérimée. Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- Langlois, Amédée (1857). Fouquier, Armand (ed.). Le Paris de Louis-Philippe. Musée universel. I. Paris: Lebrun. p. 376.

Bibliography

- Lance, Adolphe (1872). Dictionnaire des architectes français [Dictionary of French architects] (in French). I (AK). Paris: Morel. pp. 118–119.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bauchal, Charles (1887). Nouveau dictionnaire biographique et critique des architectes français [New biographical and critical dictionary of French architects] (in French). Paris: André, Daly fils & Co. p. 618.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- David de Pénanrun, Louis Thérèse; Delaire, Edmond Augustin; Roux, Louis François (1907). Les Architectes élèves de l'école des beaux-arts : 1793–1907 [The Architecture students of the school of Fine Arts 1793–1907]. Librairie de la construction moderne (in French) (2 ed.). Paris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pinon, Pierre (2002). Atlas du Paris haussmannien (in French). Paris: Parigramme. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-2840962045.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Drawings by Félix Callet in the database Cat'zArts of the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts