Ezra's Tomb

Ezra's Tomb or the Tomb of Ezra (Arabic: العزير, romanized: Al-ʻUzair, Al-ʻUzayr, Al-Azair) is a Shi'ite Islam and Jewish shrine, located in the settlement of Al-ʻUzair, in the Qalat Saleh district, in the Maysan Province of Iraq; on the western shore of the Tigris that was popularly believed to be the burial place of the biblical figure Ezra.

| Ezra's Tomb | |

|---|---|

Ezra's Tomb main building | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Islamic mosque and Jewish shrine |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Al-Uzair, Qalat Saleh district, Maysan Province, Iraq |

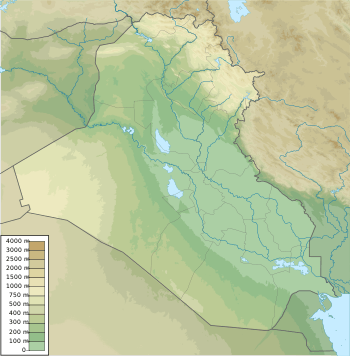

Location in Iraq | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31.3288°N 47.4186°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Islamic architecture |

| Completed | c. 1800 CE |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 1 |

| Shrine(s) | 1 |

History

The Jewish historian Josephus wrote that Ezra died and was laid to rest in the city of Jerusalem.[1] Hundreds of years later, however, a spurious tomb in his name was claimed to have been discovered in Iraq around the year 1050.[Note a][2][3]

The tombs of ancient prophets were believed by medieval people to produce a heavenly light;[Note b][4] it was reputed that on certain nights an "illumination" would go up from the tomb of Ezra.[5] In his Concise Pamphlet Concerning Noble Pilgrimage Sites, Yasin al-Biqai (d. 1095) wrote that the “light descends” onto the tomb.[6]:23 Jewish merchants partaking in mercantile activities in India from the 11th-13th century often paid reverence to him by visiting his tomb on their way back to places like Egypt.[7][8] The noted Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela (d. 1173) visited the tomb and recorded the types of observances that both Jews and Muslims of his time afforded it. A fellow Jewish traveler named Yehuda Alharizi (d. 1225) was told a story during his visit (c. 1215) about how a shepherd had learned of its place in a dream 160 years prior. Alharizi, after stating that he initially considered the accounts of lights rising from the tomb "fictitious", claimed that on his visit he saw a light in the sky "clear like the sun [...] illuminating the darkness, skipping to the right and left [...] visibly arising, moving from the west to the east on the face of heaven, as far as the grave of Ezra".[9] He also commented the light that shown on the tomb was the “glory of God.”[6]:21 Rabbi Petachiah of Ratisbon gave a similar account to Alharizi of the tomb's discovery.[10]

Working in the 19th century, Sir Austen Henry Layer suggested the original tomb had probably been swept away by the ever-changing course of the Tigris since none of the key buildings mentioned by Tudela were present at the time of his expedition.[11] If true, this would mean the current tomb in its place is not the same one that Tudela and later writers visited. It continues to be an active holy site today.[12]

The shrine

The present buildings, which unusually comprised a joint Muslim and Jewish shrine, are possibly around 250 years old; there is an enclosing wall and a blue-tiled dome, and a separate synagogue, which though now disused has been kept in good repair in recent times.[13]

Claudius James Rich noted the tomb in 1820; a local Arab told him that "a Jew, by name Koph Yakoob, erected the present building over it about thirty years ago".[14] Rich stated the shrine had a battlemented wall and a green dome (later accounts describe it as blue), and contained a tiled room in which the tomb was situated.

The shrine and its associated settlement seem to have been used as a regular staging post on journeys upriver during the Mesopotamian Campaign and British Mandate of Mesopotamia, so is mentioned in several travelogues and British military memoirs of the time.[Note c][15] T. E. Lawrence, visiting in 1916, described the buildings as "a domed mosque and courtyard of yellow brick, with some simple but beautiful glazed brick of a dark green colour built into the walls in bands and splashes [...] the most elaborate building between Basra and Ctesiphon".[16] Sir Alfred Rawlinson, who saw the shrine in 1918, observed that a staff of midwives was maintained for the benefit of women who came to give birth there.[17]: [Note c]

The vast majority of the Iraqi Jewish population emigrated in 1951–52. The shrine has continued in use, however; having long been visited by the Marsh Arabs, it is now a place of pilgrimage for the Shi'a of southern Iraq.[18] The Hebrew inscriptions of the wooden casket, the dedication plaque, and large Hebrew letters of God's name are still prominently maintained in the worshiping room.

Architecture

The mosque has a blue-tiled dome over the Darih (mausoleum) of Ezra. The Darih has no windows but an entrance. Inside the Darih there is a wooden cenotaph with inscriptions on it. The architecture of the mosque is very similar to other Shia Shrines in Iraq.

Al-Uzair town

Al-Uzair is one of the two sub-districts of Qalat Saleh district, Maysan Province. The town itself now has a population of some 44,000 people.

Gallery

Ezra's Tomb by British war artist Donald Maxwell, c. 1918.

Ezra's Tomb by British war artist Donald Maxwell, c. 1918. Photograph of Ezra's Tomb, early 20th century. The dome is hidden by date palms.

Photograph of Ezra's Tomb, early 20th century. The dome is hidden by date palms. The darih under the dome

The darih under the dome

Notes

- ^Note a : According to a legend circulating among the Jews of Yemen, Ezra died in Iraq as a punishment from God for prohibiting them from ever returning to Jerusalem.

- ^Note b : Tales of this phenomenon circulated as far as China. During the Song Dynasty, Zhou Qufei (周去非, c. 1178) wrote the tomb of Muhammad, known as the Buddha Ma-xia-wu (麻霞勿), had "such a refulgence that no one [could] approach it, those who [did] shut their eyes and [ran] by." Borrowing heavily from Zhou, the later Song scholar Zhao Rugua (c. 1225) said anyone who approached the tomb "[lost] his sight."

- ^Note c : Most mention the striking blue dome, a notable landmark in a region with few buildings. An example is in the memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs, who states: "That entertaining writer's mausoleum is in my opinion a seventeenth-century structure."

- ^Note d : Rawlinson rather flippantly characterises the shrine as "a kind of hotel."

References

- Marcus, David; Haïm Z'ew Hirschberg; Abraham Ben-Yaacob (2007). "Ezra". In Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred (eds.). Encyclopaedia Judaica. Vol. 6 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 652–654 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- Parfitt, Tudor (1996). "The road to Redemption: the Jews of the Yemen: 1900 - 1950". Brill's series in Jewish studies. Leiden [u.a.]: Brill (17): 4.

- Gordon, Benjamin Lee (1919). New Judea; Jewish Life in Modern Palestine and Egypt. Philadelphia: J.H. Greenstone. p. 70.

- Zhao, Rukuo; Hirth, Friedrich; Rockhill, William Woodville (1966). Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-Fanchï. New York: Paragon Book Reprint Corp. p. 125.

- Sirriyeh, E. (2005). Sufi Visionary of Ottoman Damascus. Routledge. p. 122.

- Meri, Joseph W. (2002). The Cult of Saints Among Muslims and Jews in Medieval Syria. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goitein, S. D. (1999). A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish Communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza – The Individual. Vol. 5. Berkeley, Calif. [a.u.]: Univ. of California Press. p. 18.

- Gitlitz, David M.; Davidson, Linda Kay (2006). Pilgrimage and the Jews. Westport: CT: Praeger. p. 97.

- Alharizi, transl. in Benisch, A. Travels of Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon, London: Trubner & C., 1856 pp. 92-93

- Petachia of Ratisbon, Rabbi. Travels of Rabbi Petachia of Ratisbon, who in the latter end of the 12. century, visited Poland, Russia, Little Tartary, the Crimea, Armenia ...: translated ... by A. Benisch, with explanat. notes by the translat. and William Francis Ainsworth. London: Trubner & C., 1856, pp. 91 n. 56

- Layard, Austen Henry, and Henry Austin Bruce Aberdare. Early Adventures in Persia, Susiana, and Babylonia, Including a Residence Among the Bakhtiyari and Other Wild Tribes Before the Discovery of Nineveh. Farnborough, Eng: Gregg International, 1971, pp. 214-215

- Raheem Salman, “IRAQ: Amid war, a prophet’s shrine survives,” LA Times blog, August 17, 2008

- Yigal Schleifer, Where Judaism Began

- Rich, C. J. Narrative of a residence in Koordistan, J. Duncan, 1836, p.391

- Storrs, Ronald (1972). The Memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs. Ayer. p. 230.

- Lawrence, T. E. (18 May 1916). "Letter". telawrence.net. Archived from the original on 31 May 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- Rawlinson, A. (1923). "Chapter 2". Adventures in the Near East, 1918-1922. Melrose.

- Raphaeli, N. "The Destruction of Iraqi Marshes and Their Revival". memri.org.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ezra's Tomb. |

.jpg)