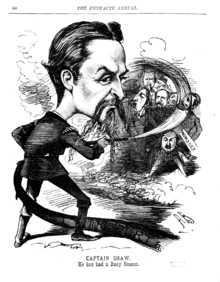

Eyre Massey Shaw

Captain Sir Eyre Massey Shaw KCB (17 January 1830 – 25 August 1908[1]) was the first Chief Officer of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (now renamed the London Fire Brigade), and the Superintendent of its predecessor, the London Fire Engine Establishment, from 1861 to 1891.[2] He introduced modern firefighting methods to the Brigade, and increased the number of stations.[3]

Eyre Massey Shaw | |

|---|---|

Colourised photograph of Captain Shaw | |

| Born | 17 January 1830 Ballymore, County Cork, Ireland |

| Died | 25 August 1908 (aged 78) Folkestone, Kent, England |

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery, London |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Dublin |

| Title | Superintendent of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade |

| Term | 1861–1891 |

| Predecessor | James Braidwood |

| Successor | James Sexton Simmonds |

| Awards | Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath |

| Military career | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1854–1860 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | North Cork Rifles |

Early career

Shaw was born in Ballymore, County Cork, Ireland and was educated first at a school in Queenstown and then at Trinity College, Dublin.[4] Shaw considered joining the Church but decided on a career in the Army and gained a commission in the North Cork Rifles, a militia regiment of the British Army (later the 9th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps) from 1854 to 1860, reaching the rank of captain.[4] He resigned from the Army on being appointed Chief Constable of Belfast Borough Police in June 1860, in charge of both the police and the fire brigade.[4] In September 1861, following the death of the then head, James Braidwood, in the line of duty while fighting a massive fire in Tooley Street, Shaw was engaged as head of the London Fire Engine Establishment.[4]

Metropolitan Fire Brigade

In 1865, Parliament passed the Metropolitan Fire Brigade Act, placing responsibility for fire protection in the Metropolitan Fire Brigade (combining the former London Fire Engine Establishment and the Society for the Protection of Life from Fire), to be supervised by the Metropolitan Board of Works. Shaw headed the new brigade.[5][6]

Shaw was an influential thinker on firefighting, publishing at least one book on the subject. He is noted for his introduction of uniforms and the famous brass helmets (c. 1868), and for introducing a ranking system. He also introduced the use of the electrical telegraph for communication between stations (c. 1867),[7][8] and stand pipes and fire hydrants.[9]

As London grew during the late 19th century, Shaw expanded the number of fire stations. In 1861, the LFEE had comprised 17 land and two river stations and 129 men; when he retired 30 years later, the brigade's estate comprised 55 land and four river stations, 127 street escape and hose-cart stations, 675 personnel and 131 horses. Sloping floors in fire stations allowed engines to move out more easily ('on the run', a term still used today).[7] Under his leadership, he also procured steam fire engines, contacting the main manufacturers, Merryweather & Sons and Shand Mason, and working with them to develop an engine which could be pulled by two horses and produce several jets at high pressure (on average, 300 gallons of water per minute).[7]

Shaw was a well-known socialite (which led to his immortalisation in operetta, see below) and a personal friend of the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII). A firefighting outfit was always kept ready at Charing Cross Fire Station in case the Royal heir chose to firefight.[10]

When the Fire Brigade was taken over by the London County Council in 1889, he disagreed with the administration and resigned in 1891. He was knighted by Queen Victoria on his last day of service. Shaw died at Folkestone on 25 August 1908.[4]

Cultural influence and legacy

Shaw is best remembered today as the "Captain Shaw" to whom the Fairy Queen in Gilbert and Sullivan's Iolanthe addresses herself, wondering if his "brigade with cold cascade" could quench her great love. Shaw was present in the stalls at the first night of Iolanthe in 1882, and Alice Barnett, playing the Fairy Queen, addressed herself directly to him. Legend has it that he stood up and took a bow.

In 1886, Shaw was later named in an adultery lawsuit involving Lady Colin Campbell who was sitting next to Shaw at the Iolanthe premiere (source Anne Jordan biographer LCC).

In addition, a historic fireboat, named the Massey Shaw, still exists, and was recently renovated. Built in 1935, it made several trips to Dunkirk during the evacuation of British troops from France in 1940.[11]

Winchester House, the headquarters of the Metropolitan Fire brigade in Southwark, which also included a residence for Shaw,[9] later became the London Fire Brigade Museum (now closed); an English Heritage Blue plaque still adorns the building and states that Shaw lived there.[12]

References

- Newmann, Kate (2012). "Eyre Massey Shaw". The Dictionary of Ulster Biography. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- Austin Macauley Publishers (ISBN 978-1-78455-541-2)

- http://www.angliacampus.com/education/fire/london/history/victoria.htm Archived 25 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sir Eyre Massey Shaw". Obituaries. The Times (38735). London. 26 August 1908. col B, p. 11.

- Fire Brigade history at www.firebrigadehistory.netfirms.com Archived 4 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- History at www.aovq74.dsl.pipex.com Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Sir Eyre Massey Shaw". Massey Shaw Educational Trust. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Telegraph". London Fire Journal. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "London Fire Brigade Museum, Winchester House". London buses: and now London's Museums. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- "Chief Officer Captain Shaw". London Fire Brigade. 2012. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- "Massey Shaw". Association of Dunkirk Little Ships. 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- "Shaw, Sir Eyre Massey (1830–1908)". English Heritage. 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Captain Eyre Massey Shaw. |