Eye Castle

Eye Castle is a motte and bailey medieval castle with a prominent Victorian addition in the town of Eye, Suffolk. Built shortly after the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the castle was sacked and largely destroyed in 1265. Sir Edward Kerrison built a stone house on the motte in 1844: the house later decayed into ruin, becoming known as Kerrison's Folly in subsequent years.

| Eye Castle | |

|---|---|

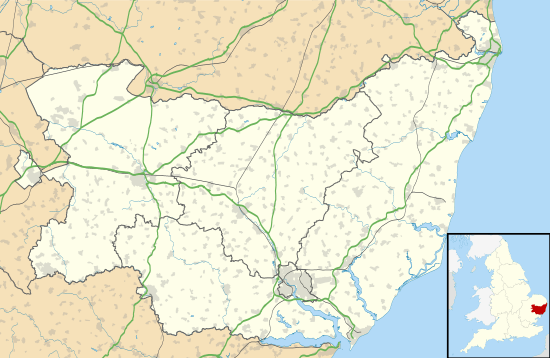

| Eye, Suffolk, Suffolk, England | |

Eye Castle, with 11th century motte and bailey, and Victorian ruin | |

Eye Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52.3202°N 1.1503°E |

| Grid reference | grid reference TM148738 |

| Type | Motte and bailey, with later Victorian addition |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Flint |

History

11th–13th centuries

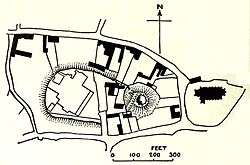

Eye Castle is a motte and bailey castle, built during the reign of William I by William Malet, who died fighting Hereward the Wake in 1071.[1] The Malet family also controlled the surrounding Honour of Eye, a significant collection of estates centering on the castle, and the park of Eye.[2] The castle motte is 160 feet (49 m) in diameter and 40 feet (12 m) high, with the bailey approximately 400 feet (122m) by 250 feet (76 m) wide.[3] The castle is unusual in being only of two castles mentioned in the Domesday book on 1086 as a source of income for their owners, due to the presence of a market within the castle, bailey, from which the owner drew revenue; the castle's market competed with the Bishop of Norwich's market at Hoxne.[4]

William Malet's son, Robert, was exiled and after his death at the battle of Tinchebrai in 1106, Eye was confiscated by Henry I and became a royal castle for a period.[5] Henry gave Eye to his favoured nephew, Stephen of Blois in 1113.[6] Stephen succeeded to the English throne in 1135 and he gave the honour of Eye first to one of his lieutenants, William of Ypres and then later to Hervey Brito, his son-in-law.[7] At some point during the 1140s, Stephen then transferred the lands to his second son, William.[8] William was still young at the time, and it appears that until he came of age these lands were initially managed by Stephen's trusted Royal Steward, William Martel.[8] Meanwhile, the civil war known as the Anarchy had broken out between Stephen and the Empress Matilda between 1138 and 1154; much of the fighting occurred in East Anglia, where the powerful Bigod family, headed by Hugh Bigod, attempted to expand their autonomy and influence. Eye Castle did not play a major role in the war as, despite some skirmishing occurring in the region, most of the campaigning was conducted to the west.[9]

After coming to power in 1154, Henry II attempted to re-establish royal influence across the region.[10] Partially as a result of the civil war, Hugh Bigod had come to dominate East Anglia by the late 12th century, holding the title of the Earl of Norfolk and owning the four major castles in the region, Framlingham, Bungay, Walton and Thetford.[11] As part of this effort, Henry confiscated the Bigod castles, from Hugh in 1157.[12] Despite having made earlier promises to protect him, Henry still saw Stephen's son, William, as a potential claimant to the throne, and the king confiscated the castle of Eye as well at the same time.[13] William died in 1159, allowing Henry to formally acquire and thereby legitimise his control of Eye Castle.[14]

Hugh then joined the revolt by Henry's sons in 1173. Eye was attacked by Hugh Bigod in 1173. Although the attack failed, the castle had to be rebuilt. Two square towers were built on the north side of the inner bailey in the late 12th century, possibly contemporaneously with Framlingham.[15] The castle was protected using the castle-guard system, under which local lands were granted to minor lords in exchange for the contribution of knights and soldiers for the defence of the castle.[16]

The castle was attacked and sacked in 1265 during the Second Barons' War; it was subsequently largely abandoned.[17]

14th–21st centuries

By the 14th century, Eye Castle lay largely in ruins, although parts of the castle continued to be maintained as a prison.[17] Despite the ruined nature of the castle, the local estates previously subject to the castle-guard system continued to return their dues, now converted into monetary rents, to the owners of Eye Castle for many years.[18] A windmill was built on top of the motte between 1561-2.[19] In the early 17th century, like many other medieval Suffolk parks, the park of Eye around the castle was broken up and turned into fields.[20]

In the 1830s a workhouse and a school were built inside the castle bailey.[17] In 1844 the owner, Sir Edward Kerrison, demolished a later windmill that had been built on the motte, and replaced it with a domestic house.[17] Kerrison had the dwelling built for his batman, who had saved his life at the battle of Waterloo in 1815.[19] The house resembled a shell keep, and was built of flint and had living quarters built into the walls on the south and west.[19] The building fell into ruins, being damaged in high winds during 1965 and collapsing further in 1965.[19] It is now sometimes now referred to as Kerrison's Folly.[21] The mound and some stone fragments of the original castle still remain intact, and the site is a scheduled monument and a Grade 1 listed building.

References

- Pettifer, p.233.

- Scarfe, p.151; Hoppitt, p.163.

- Wall, p.596.

- Creighton, pp.94, 165.

- Pettifer, p.233; Davis, p.7; King (2010), p.13

- Davis, p.7; King, p.13

- King (2010), pp.129, 138.

- Brown (1994), p.28.

- Davis, pp.84-5; King (2010), p.220

- Pounds, p.55.

- Pounds, p.55; Brown (1962), p.191.

- Brown (1962), p.191.

- Brown (1962), p.191; Warren, p.67.

- Warren, p.235.

- Kenyon, p.73.

- King (1991), p.16.

- Suffolk HER EYE 016, Suffolk Historic Environmental Record, accessed 24 June 2011.

- King (1991), p.18.

- Eye Castle, List No. 1316598 Archived 2012-10-13 at the Wayback Machine, National Heritage List, English Heritage, accessed 28 June 2011.

- Hoppitt, p.162.

- Suffolk HER EYE 016, Suffolk Historic Environmental Record, accessed 24 June 2011; Pettifer, p.233.

Bibliography

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Brown, Vivien. (1994) Eye Priory Cartulary and Charters, Part 2. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-347-6.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Davis, R. H. C. (1977) King Stephen. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-48727-7.

- Hoppitt, Rosemary. (2007) "Hunting Suffolk's Parks: Towards a Reliable Chronology of Imparkment," in Liddiard (ed) (2007)

- Kenyon, John R. (2005) Medieval Fortifications. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7886-3.

- King, D. J. Cathcart. (1991) The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-00350-4.

- King, Edmumd. (2010) King Stephen. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11223-8.

- Liddiard, Robert. (ed) (2007) The Medieval Park: New Perspectives. Bollington, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 978-1-905119-16-5.

- Page, William. (ed) (1911) The Victoria History of Suffolk, Vol. 1. London: University of London.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2002) English Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Scarfe, Norman. (1986) Suffolk in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-068-9.

- Wall, J. C. (1911) "Ancient Earthworks," in Page (ed) (1911).

- Warren, W. L. (2000) Henry II. New Haven, US: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08474-0.