Exoticism

Exoticism (from 'exotic') is a trend in European art and design, whereby artists became fascinated with ideas and styles from distant regions, and drew inspiration from them. This often involved surrounding foreign cultures with mystique and fantasy which owed more to European culture than to the exotic cultures themselves: this process of glamorisation and stereotyping is called 'exoticization'.

History of exoticism

The word 'exotic' is rooted in the Greek word exo ('outside') and means, literally, 'from outside'. It was coined during Europe's Age of Discovery, when 'outside' seemed to grow larger each day, as Western ships sailed the world and dropped anchor off other continents. The first definition of 'exotic' in most modern dictionaries is 'foreign', but while all things exotic are foreign, not everything foreign is exotic. Since there is no outside without an inside, the foreign only becomes exotic when imported – brought from the outside in. From the early seventeenth century, 'exotic' has denoted enticing strangeness – or, as one modern dictionary puts it, "the charm or fascination of the unfamiliar". [1]

First stimulated by Eastern trade in the 16th and 17th centuries, interest in non-western (particularly "Oriental", i.e. Middle Eastern or Asian) art by Europeans became more and more popular following European colonialism.[2]

The influences of Exoticism can be seen through numerous genres of this period, notably in music, painting, and decorative art. In music, exoticism is a genre in which the rhythms, melodies, or instrumentation are designed to evoke the atmosphere of far-off lands or ancient times (e.g., Ravel's Daphnis et Chloé and Tzigane for Violin and Orchestra, Debussy's Syrinx for Flute Solo or Rimsky-Korsakov's Capriccio espagnol). Like orientalist subjects in 19th-century painting, exoticism in the decorative arts and interior decoration was associated with fantasies of opulence.

Exoticism, by one definition, is "the charm of the unfamiliar". Scholar Alden Jones defines exoticism in art and literature as the representation of one culture for consumption by another.[3] Victor Segalen's important "Essay on Exoticism" reveals Exoticism as born of the age of imperialism, possessing both aesthetic and ontological value, while using it to uncover a significant cultural "otherness".[4] An important and archetypical exoticist is the artist and writer Paul Gauguin, whose visual representations of Tahitian people and landscapes were targeted at a French audience. While exoticism is closely linked to Orientalism, it is not a movement necessarily associated with a particular time period or culture. Exoticism may take the form of primitivism, ethnocentrism, or humanism.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (29 August 1780 – 14 January 1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. The revival of ancient Greek and Roman art left behind the Academy’s emphasis on naturalism, and incorporated a new found idealism not seen since the Renaissance.[5] As classicism progressed, Ingres identified a newfound idealism and exoticism in his work. The Grand Odalisque, finished in 1814, was created to arouse the male view.[6] The notion of the exotic figure furthers Ingres’ use of symmetry and line by enabling the eye to cohesively move across the canvas.[7] Although Ingres’ intention was to make the woman beautiful in his work, his model was a courtesan, which arouse debate.

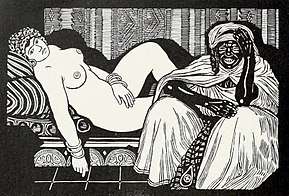

Édouard Manet’s Olympia, finished in 1863, was based on Titian’s Venus of Urbino.[8] Olympia was a popular play about a courtesan called Olympia. This subject was extremely controversial for an artist to portray a woman like this because of traditional vision of the Academy. Manet was being very different from the accepted academic style by outlining and flattening space that created a distortion of classical elements. Olympia is provocative in her nudity that implies she is naked, not nude.[9] She is looking out in a very confrontational way, and setting the viewer as a man coming to the prostitute, although Olympia’s hand suggests she is not ready to engage with the customer.[10] The African servant calls on racism and slavery in France, because showing someone of color participating in French life was unheard of, furthering the work's exotic nature.

See also

Notes

- Sund, Judy. "Exotic – a Fetish for the Foreign". GDC interiors Journal.

- Oshinsky, Sara J. "Exoticism in the Decorative Arts". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Alden Jones (August 6, 2007). "This Is Not a Cruise". The Smart Set.

- Segalen, Victor (2002). Essay on Exoticism: An Aesthetics of Diversity. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Herbert, Robert (1990). "Art, Leisure, and Parisian Society". Art Journal. 49 (1): 65.

- Carter, Karen (2012). "The Spectatorship of the Affiche Illustrée and the Modern City of Paris, 1880-1900". Journal of Design History. 25 (1): 24. doi:10.1093/jdh/epr044.

- Chu, Petra (2011). Nineteenth-Century European Art. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 87.

- Chu, Petra (2011). Nineteenth Century European Art. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 233.

- Chu, Petra (2011). Nineteenth Century European Art. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 235.

- Chu, Petra (2011). Nineteenth Century European Art. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 236.

References

- George Rousseau and Roy Porter (1990). Exoticism in the Enlightenment (Manchester: Manchester University Press). ISBN 0-567-09330-1

- The Smart Set: Alden Jones on Teaching Exoticism on Semester at Sea

- Segalen, Victor. Essay on Exoticism: An Aesthetics of Diversity. Trans. Yaël Rachel Schlick. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

External links

| Look up exoticism in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- GDC interiors Journal 'Exotic – a Fetish for the Foreign' by Judy Sund

- Exoticism in Decorative Arts

- Exoticism in Tang

- Exoticism in the Literature of 1930s