Exhumation of Yagan's head

The exhumation of Yagan's head was the result of a geophysical survey and archaeological dig at a grave site in the Everton Cemetery, Liverpool in 1997.

Background

Yagan was an indigenous Australian warrior of the Noongar nation who played a key part in early indigenous resistance to European settlement and rule around the area of Perth, Western Australia. He was shot dead by a young settler, James Keates in 1833. Yagan's head was removed, preserved by smoking, and taken to England by Robert Dale, who gave it to the Liverpool Institute for display in a museum.[1]

By 1964, Yagan's head was badly decomposed, and the decision was made to dispose of it. The head was placed in a plywood box, along with a Peruvian mummy and a Māori head, and buried in Everton Cemetery's General Section 16, grave number 296. In later years, a number of burials were made around the grave, and in 1968 a local hospital buried 20 stillborn babies and two babies who had lived less than twenty-four hours, directly over the museum box.[2]

For many years, members of Perth's Noongar community sought to have Yagan's head returned and buried according to tribal custom. An application for exhumation of the head was made in 1994, but it was refused because next of kin permission to disturb the remains of the twenty-two babies could not be obtained.[2]

The geophysical survey

In 1997, two brothers, Dr Martin Bates of the University of Wales, Lampeter and Dr Richard Bates of the University of St Andrews, were commissioned by the Home Office to conduct a geophysical survey of the grave site, with a view to exhuming the remains via an adjacent plot without disturbing any other remains.[2]

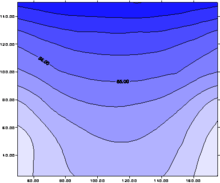

The pair conducted surface surveys using ground penetrating radar and ground conductivity techniques. The ground penetrating radar yielded no information about the location of Yagan's head, as the highly disturbed graveyard soil contained many reflecting sources. However, the ground conductivity measurements showed an anomaly in the electromagnetic signature that it was thought might be caused by metal artifacts buried with the head. The apparent location of the remains confirmed the feasibility of accessing them via an adjacent plot.[3][4]

A pit was then dug in an adjacent plot, to a depth of around six feet, and a vertical ground conductivity test was conducted from within the pit. This test failed to detect the anomaly recorded in the surface test, however the conductivity plot did show an anomaly at the centre of the grave, indicating that the grave was dug to its full depth of nine feet only at its centre. This suggested the burial of a small box, confirming the memory of the grave digger who claimed to have constructed a small box to house the buried remains.[3][4]

The exhumation

After gathering evidence on the position and depth of Yagan's head, Bates reported the survey results to the Home Office, which eventually granted permission to proceed with the exhumation. Yagan's head was exhumed by tunnelling horizontally into the grave from the adjacent pit. The tunneling operation was "delicate and risky", as the tunnel passed underneath the remains of the babies, such that any collapse could potentially disturb them. According to Richard Bates, "the first shovel of dirt from the grave showed signs of the decayed box and the Peruvian mummy came next followed by the Māori head and finally Yagan's head".[3][4]

The following day, a forensic palaeontologist from the University of Bradford positively identified the skull as Yagan's, by correlating the fractures with those described in an 1834 report by Thomas Pettigrew.[2]

Aftermath

Later that year, Yagan's head was handed over to a delegation of Noongars, who took it back to Australia. Reburial of the head was delayed, however, due to uncertainty of the whereabouts of the rest of his body and disagreement by elders about the importance of burying the head with the body.[2] They finally buried it in July 2010, in a traditional Noongar ceremony in the Swan Valley in Western Australia, 177 years after Yagan's death.[5]

References

- Turnbull, Paul (1998). ""Outlawed Subjects": The Procurement and Scientific Uses of Australian Aboriginal Heads, ca. 1803–1835". Eighteenth-Century Life. 22 (1): 156–171.

- Fforde, Cressida (2002). "Chapter 18: Yagan". In Fforde, Cressida; Hubert, Jane; Turnbull, Paul (eds.). The Dead and Their Possessions: Repatriation in Principle, Policy, and Practice. London: Routledge. pp. 229–241. ISBN 0-415-23385-2.

- "Archaeological Geophysics: Yagan's Head". Retrieved 29 February 2008.

- Bates, C. R. (2005) pers. comm.

- Warrior reburied 170 years after death Archived 2013-06-23 at the Wayback Machine, Australian Geographic, 12 July 2010

Further reading

The following source was not consulted in the writing of this article:

- Bates, M and Bates, C. R. (1997) A Report on the Geophysical Investigation of the Site of a Grave in Everton Cemetery, Liverpool, Unpublished Technical Report.