Eugen Müller

Eugen Müller (19 July 1891 – 24 April 1951) was a German general in the Wehrmacht during World War II. He is known for having drafted the criminal Commissar order in preparation for Operation Barbarossa, the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union.

Eugen Müller | |

|---|---|

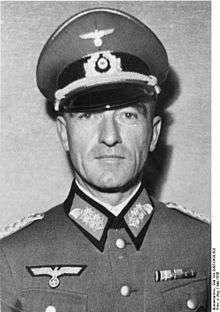

Müller in May 1939. | |

| Born | 19 July 1891 Metz, Lothringen, German Empire |

| Died | 24 April 1951 (aged 59) Berlin, West Germany |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Army |

| Years of service | 1910–45 |

| Rank | General of the Artillery |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II |

Career

Born in 1891, Müller enlisted in the army in 1912 and served during World War I. He was retained by the Reichswehr and then the Wehrmacht, reaching the rank of Colonel in 1935. On 1 April 1939, Müller was promoted to the rank of Generalmajor and took command of the War Academy.

1 September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, Müller was assigned to the Headquarters Chief of Staff of the Army, under the command of Franz Halder. Müller was in charge of legal and criminal action relating to the occupied areas in Europe. He remained at the General Staff until the end of the war.

Commissar order

The first draft of the Commissar Order was issued by General Eugen Müller on May 6, 1941 and called for the shooting of all commissars in order to avoid letting any captured commissar reach a POW camp in Germany.[1] The German historian Hans-Adolf Jacobsen wrote:

"There was never any doubt in the minds of German Army commanders that the order deliberately flouted international law; that is borne out by the unusually small number of written copies of the Kommissarbefehl which were distributed".[1]

The paragraph in which General Müller called for Army commanders to prevent "excesses" was removed on the request of the OKW.[2] Brauchitsch amended the order on May 24, 1941 by attaching Müller's paragraph and calling on the Army to maintain discipline in the enforcement of the order.[2] The final draft of the order was issued by OKW on June 6, 1941 and was restricted only to the most senior commanders, who were instructed to inform their subordinates verbally.[2]

The enforcement of the Commissar Order led to thousands of executions.[3] The German historian Jürgen Förster wrote in 1989 that it was simply not true, as most German Army commanders claimed in their memoirs and some German historians like Ernst Nolte were still claiming, that the Commissar Order was not enforced.[3] On September 23, 1941, after several Wehrmacht commanders had asked for the order to be softened as a way of encouraging the Red Army to surrender, Hitler declined "any modification of the existing orders regarding the treatment of political commissars".[4]

References

- Jacobesn, Hans-Adolf "The Kommisssarbefehl and Mass Executions of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War" pages 505-536 from Anatomy of the SS State, Walter and Company: New York, 1968 pages 516-517

- Jacobesn, Hans-Adolf "The Kommisssarbefehl and Mass Executions of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War" pages 505-536 from Anatomy of the SS State, Walter and Company: New York, 1968 page 519.

- Förster, Jürgen "The Wehrmacht and the War of Extermination Against the Soviet Union" pages 494-520 from The Nazi Holocaust page 502

- Jacobesn, Hans-Adolf "The Kommisssarbefehl and Mass Executions of Soviet Russian Prisoners of War" pages 505-536 from Anatomy of the SS State, Walter and Company: New York, 1968 page 522.

Sources

- Andreas Toppe: 'Militär und Kriegsvölkerrecht: Rechtsnorm, Fachdiskurs und Kriegspraxis in Deutschland 1899–1940'. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, München, 2008.

- Christian Streit: 'Keine Kameraden: die Wehrmacht und die sowjetischen Kriegsgefangenen 1941–1945'. Dietz-Verlag, Bonn, 1997.