Esemplastic

Esemplastic is a qualitative adjective which the English romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge claimed to have invented. Despite its etymology from the Ancient Greek word πλάσσω for "to shape", the term was modeled on Schelling's philosophical term Ineinsbildung – the interweaving of opposites – and implies the process of an object being moulded into unity.[1] The first recorded use of the word is in 1817 by Coleridge in his work, Biographia Literaria, in describing the esemplastic – the unifying – power of the imagination.[2]

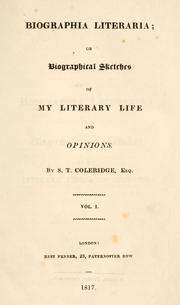

Biographia Literaria

The Biographia Literaria was one of Coleridge's main critical studies in which he discusses the elements and process of writing. In this work, Coleridge establishes a criterion for good literature, making a distinction between the imagination and "fancy". Whereas fancy rested on the mechanical and passive operations of one's mind to accumulate and store data, imagination held a "mysterious power" to extract "hidden ideas and meaning" from such data. Thus, Coleridge argues that good literary works employ the use of the imagination and describes its power to "shape into one" and to "convey a new sense" as esemplastic. He emphasizes the necessity of creating such a term as it distinguishes the imagination as extraordinary and as "it would aid the recollection of my meaning and prevent it being confounded with the usual import of the word imagination".[3]

Usage

Use of the word has been limited to describing mental processes and writing, such as "the esemplastic power of a great mind to simplify the difficult",[4] or "the esemplastic power of the poetic imagination". The meaning conveyed in such a sentence is the process of someone, most likely a poet, taking images, words, and emotions from a number of realms of human endeavor and thought and unifying them all into a single work. Coleridge argues that such an accomplishment requires an enormous effort of the imagination and, therefore, should be granted with its own term. The invention of this word was met with controversy;[5] the Scottish philosopher J. F. Ferrier wrote a scathing comment: "You there [in Schelling's Darlegung] found the word In-eins-bildung—“a shaping into one”—which Schelling or some other German had literally formed from the Greek, εἰς ἓν πλάττειν, and you merely translated this word back into Greek, (a very easy and obvious thing to do,) and then you coined the Greek words into English, merely altering them from a noun into an adjective."[2] The term is infrequently used in modern speech and text, and has only appeared in two other literary works.

References

- "Oxford English Dictionary". Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Carver, P. L. (July 1929). "The Evolution of the Term "Esemplastic"". Modern Humanities Research Association. 24: 329–331. JSTOR 3715968.

- Shahid, Sana. "Coleridge "Imagination and Fancy"".

- "Esemplastic". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- Garg, Anu, esemplastic, A Word A Day, Wordsmith.com, September 5, 2019