Erodium cicutarium

Erodium cicutarium, also known as redstem filaree, redstem stork's bill, common stork's-bill or pinweed, is a herbaceous annual – or in warm climates, biennial – member of the family Geraniaceae of flowering plants. It is native to Macaronesia, temperate Eurasia and north and northeast Africa,[1] and was introduced to North America in the eighteenth century,[2] where it has since become naturalized, particularly of the deserts and arid grasslands of the southwestern United States.[3]

| Erodium cicutarium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Geraniales |

| Family: | Geraniaceae |

| Genus: | Erodium |

| Species: | E. cicutarium |

| Binomial name | |

| Erodium cicutarium | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Geranium cicutarium L. | |

Distribution and ecology

The plant is widespread across North America. The plant grows as an annual in the northern half of North America. In the southern areas of North America, the plant tends to grow as a biennial with a more erect habit and with much larger leaves, flowers, and fruits. It flowers from May until August. Common stork's-bill can be found in bare, sandy, grassy places both inland and around the coasts. It is a food plant for the larvae of the brown argus butterfly.

The seeds of this annual are a species collected by various species of harvester ants.[4]

Description

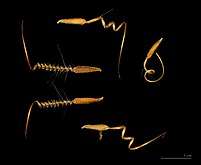

It is a hairy, sticky annual. The stems bear bright pink flowers, which often have dark spots on the bases. The flowers are arranged in a loose cluster and have ten filaments – five of which are fertile – and five styles.[5] The leaves are pinnate to pinnate-pinnatifid, and the long seed-pod, shaped like the bill of a stork, bursts open in a spiral when ripe, sending the seeds (which have long tail called awns) into the air.

Seed dispersal behavior

Erodium cicutarium seed uses self-dispersal mechanisms to spread away from the maternal plant and also to reach good germination site to increase fitness. Two techniques that Erodium uses are explosive dispersal which launch seeds by storing elastic energy, and self-burial dispersal where Erodium seeds move themselves across the soil using hygroscopically powered shape change.[6]

Explosive dispersal

After flowering, the five pericarps on the fruits of Erodium, and the awns, which are hair like appendages of pericarps, joined together and grow into a spine shape. As the fruits dry, dehydration create tension, and elastic energy develops within the awns. The shape of the awns change from straight to helical, causing them to explosively separate the seeds away from the maternal plants.[7] During dispersal, mechanical energy stored in specialized tissues is transferred to the seeds to increase their kinetic and potential energy. The energy storage capacity of the seeds is determined by the level of hydration, suggesting a role of turgor pressure in the explosive dispersal mechanism.[8]

Self-burial dispersal

The awn of each seed, once on the ground, responds to humidity of the environment and changes its shape accordingly. The awn coils under dehydration and uncoils when wet. This results in motor action of the seed, which, combined with hairs on the seed and along the length of the awns, moves the seed across the surface, eventually positioning them into a crevice and creating a drilling action that forces the seed into the ground. The coil and uncoil of the awns are achieved by the hygroscopic tissue in the active layer on the awns. Hygroscopic movement happens with respond to a change in the water content of dead plant tissue, specially in the cell wall. Water absorbed by the cell wall binds to the matrix of the awns, causing it to expand and to drive the cellulose microfibrils apart, which causes the matrix to uncoil, thus straightening the awns. Inversely, the matrix will contract under dehydration, leading to the coil of the awns.[9]

Research found no correlation between weight of the awned fruits and the dispersal distance.[3] E.cicutarium with larger seeds have a longer coil and uncoil time compare to smaller seeds. In the field, the rate of seed burial declined throughout the season. The larger seeds buried themselves more often than the smaller seeds. However, larger seeds have a harder time finding a large enough space for the seeds to be buried. Conversely, smaller seeds have an easier time finding a hole and drilling themselves in, and thus are more likely to be buried.[7]

Advantages

The advantages of explosive dispersal and self-burial dispersal are to get mature seeds of E.cicutarium quickly to the ground during the most favorable period for burial by hygroscopic mechanisms, thus increase fitness.

Uses

The entire plant is edible with a flavor similar to sharp parsley if picked young. According to John Lovell's Honey Plants of North America (1926), "the pink flowers are a valuable source of honey (nectar), and also furnish much pollen".[10] Among the Zuni people, a poultice of chewed root is applied to sores and rashes and an infusion of the root is taken for stomachache.[11]

References

- "Erodium cicutarium (L.) L'Hér.". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- Philip Stott, Scott Mensing & Roger Byrne (1998). "Pre-mission invasion of Erodium cicutarium in California". Journal of Biogeography. 25 (4): 757–762. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1998.2540757.x.

- Nancy E. Stamp (1984). "Self-burial behaviour of Erodium cicutarium seeds". Journal of Ecology. 72 (2): 611–620. doi:10.2307/2260070. JSTOR 2260070.

- G. D. Harmon & N. E. Stamp (1992). "Effects of postdispersal seed predation on spatial inequality and size variability in an annual plant, Erodium cicutarium (Geraniaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 79 (3): 300–305. doi:10.2307/2445019. JSTOR 2445019.

- David Giblin. "Erodium cicutarium, redstem stork's bill, common stork's bill". WTU Herbarium Image Collection. Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Dumais, Jacques; Hotton, Scott; Evangelista, Dennis (2011-02-15). "The mechanics of explosive dispersal and self-burial in the seeds of the filaree, Erodium cicutarium (Geraniaceae)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (4): 521–529. doi:10.1242/jeb.050567. ISSN 0022-0949. PMID 21270299.

- Stamp, N. E. (1989). "Seed Dispersal of Four Sympatric Grassland Annual Species of Erodium". Journal of Ecology. 77 (4): 1005–1020. doi:10.2307/2260819. ISSN 0022-0477. JSTOR 2260819.

- Hayashi, Marika; Feilich, Kara L.; Ellerby, David J. (2009). "The mechanics of explosive seed dispersal in orange jewelweed (Impatiens capensis)". Journal of Experimental Botany. 60 (7): 2045–2053. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp070. ISSN 1460-2431. PMC 2682495. PMID 19321647.

- Elbaum, Rivka; Abraham, Yael (2014-06-01). "Insights into the microstructures of hygroscopic movement in plant seed dispersal". Plant Science. 223: 124–133. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.03.014. ISSN 0168-9452. PMID 24767122.

- John H. Lovell (1926). Honey Plants of North America.

- Scott Camazine & Robert A. Bye (1980). "A study of the medical ethnobotany of the Zuni Indians of New Mexico". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2 (4): 365–388. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(80)81017-8. PMID 6893476.

External links

- GRIN-Global Web v 1.9.6.2: Erodium cicutarium — distribution + taxonomy.