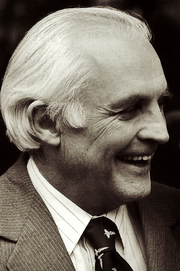

Ernst Freese

Dr. Ernst Freese (September 27, 1925 - March 30, 1990) was a molecular biologist who worked on the mechanism of mutations in DNA. From 1962 until his death he was Chief of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Laboratory of Molecular Biology at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Ernst Freese's scientific career started in theoretical particle physics and later moved to molecular biology where he contributed to early genetics research.

Ernst Freese | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 27, 1925 |

| Died | March 30, 1990 (aged 64) |

| Alma mater | University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Molecular biology research |

| Spouse(s) | Elisabeth Bautz |

| Children |

|

Education and academic career

Ernst Freese began his career as a student of physics with Werner Heisenberg at the University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, where Freese received his PhD in 1953 in work in theoretical particle physics. He came to the United States in 1954 to work as a postdoctoral fellow with Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago. He started his career in biology at Max Delbrück's laboratory at the California Institute of Technology in 1955. He held research positions at the University of Cologne (1956-1957) and Harvard University (1957-1959), where he worked with James Watson. Freese joined the University of Wisconsin as an Associate Professor of genetics in 1959 and established the university's first molecular biology program. In 1962 he moved to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as Chief of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Laboratory of Molecular Biology. He held this position until his death.[1] The other laboratory chiefs included Marshall Warren Nirenberg and Daniel Carleton Gajdusek. Freese was also the Director of the Basic Neurosciences Program at NINDS from 1987.

Contributions to molecular biology

Freese was interested in the molecular mechanism of mutations and determined the difference between spontaneous and chemical mutations by using T4 phage. In 1959 he coined the terms "transitions" and "transversions" to categorize different types of point mutations.[2][3] Point mutations, often caused by chemicals or malfunction of DNA replication, exchange a single nucleotide for another. Most common is the transition that exchanges a purine for a purine (A ↔ G) or a pyrimidine for a pyrimidine, (C ↔ T).

Freese's research also included microbial differentiation and molecular neurobiology. He studied the effect of lipophilic acids on the growth and differentiation of bacteria. Freese's laboratory worked on the metabolic control of sporulation and germination of Bacillus subtilis bacteria. He identified the key metabolite for ignition of sporulation: a decrease of GTP. Freese was cofounder of the Environmental Mutagen Society and served as its president for two years. In 1971, he organized the first comprehensive conference focused on the prospects of gene therapy through the John E. Fogarty International Center.[4] His laboratory identified certain compounds as mutagenic and he was instrumental in banning the use of certain pesticides and food additives. Later in his career, as a NIH administrator, he provided the initial support to J. Craig Venter to initiate his program to sequence the human genome.[5] His laboratory first sequenced GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein), and helped to elucidate its role in neural structure and development.[6] Throughout his career, he trained dozens of postdoctoral research fellows. He received the Alexander von Humboldt Prize in 1983.

Personal life

After meeting her at Caltech, Freese married his fellow postdoctoral fellow, Dr. Elisabeth Bautz, in 1956, and together they had two children, Katherine Freese[7] and Andrew Freese. After the death of Elisabeth, he married Katherine Bick, Ph.D. in 1985, who was the Deputy Director of Extramural Research for the National Institutes of Health.

References

- "Ernst Freese, 64, Dies; A Molecular Biologist". New York Times. April 4, 1990.

- Freese, Ernst (April 1959). "THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN SPONTANEOUS AND BASE-ANALOGUE INDUCED MUTATIONS OF PHAGE T4". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 45 (4): 622–33. doi:10.1073/pnas.45.4.622. PMC 222607. PMID 16590424.

- Freese, Ernst (1959). "The Specific Mutagenic Effect of Base Analogues on Phage T4". Journal of Molecular Biology. 1 (2): 87–105. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(59)80038-3.

- Ernst Freese, ed. (1972). The Prospects of Gene Therapy. National Institutes of Health.

- Venter, J.C. (2007). A Life Decoded: My Genome, My Life. Penguin Press. p. 101.

- Benner, M.; et al. (1990). "Characterization of human cDNA and genomic clones for glial fibrillary acidic protein". Molecular Brain Research. 7: 277–286.

- Curriculum Vitae of Katherine Freese