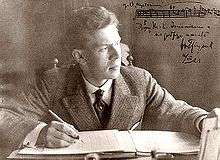

Ernest Pingoud

Life

Born in Saint Petersburg to a German-Finnish mother and a father of French Huguenot ancestry, Pingoud was a pupil of the Russian composers Anton Rubinstein, Alexander Glazunov and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory.[1] He also took private lessons with Alexander Siloti, who had come to know the family when he became a neighbour of their summer residence at Tikkala Manor near Viipuri on the Karelian Isthmus.[2] In 1906, he went to Germany to study with the music theorist Hugo Riemann and the composer Max Reger, who considered him one of his best pupils.[2] Perhaps on his father's instructions, Pingoud also studied non-musical subjects, including philosophy and literature, as well as mining and metallurgy, at Jena, Munich, Bonn and Berlin.[2] He chose to present a thesis on Goethe, which for some reason was never approved.[2] In 1908, while still a student, Pingoud began a writing career by becoming musical correspondent for the St. Petersburger Zeitung; he held the post until 1911 and then subsequently contributed concert and opera reviews from St. Petersburg until 1914.[2]

After the revolution, Pingoud moved to Helsinki where he lived for the rest of his life except for brief periods spent in Turku and Berlin. Besides his composing, he contributed to several newspapers and worked as an administrator of the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra and as director of a concert agency.

His first orchestral concert, held in Helsinki in 1918, heralded the arrival of a modernist musical aesthetic in Finland.[1] The music shocked the audience, much like their counterparts at the notorious 1913 premiere of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in Paris. Stylistically, the works showed the influence of Richard Strauss, Alexander Scriabin and Claude Debussy.[1] Hostility in Finland towards his music resulted in a string of pejorative labels, including "ultra-modernism" and even "musical Bolshevism", although his command of orchestration did eventually receive some critical acknowledgement.[1] His open rejection of Finnish nationalism may have been responsible for some of the disapproval he encountered (unlike other Finnish composers of the time he avoided composing works inspired by the Kalevala).[1][3]

Pingoud committed suicide by throwing himself under a train in Helsinki in 1942.[4]

Style

Pingoud's preferred mode of musical expression was orchestral, especially in symphonic poems following the example of Scriabin[1] His three piano concertos seem to look more to the models of Franz Liszt and Sergei Rachmaninoff.[1] Although the concision of his Fünf Sonette has been compared to early works of the Second Viennese School, his musical language remained predominantly tonal.[1] He made extensive use of the Prometheus chord and the octatonic collection.[3]

Recordings

A CD containing some of Pingoud's symphonic poems has been recorded for Ondine by the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Sakari Oramo.[5]

Works

Solo Voice

- Barcarole (Venelaulu)

- Berceuse (Kehtolaulu) Op. 11a No 3

- En blomma Op. 11a No 1

- Färden i storm (Matka myrskyssä) Op. 11a No 4

- Hjärtan fjärran och hjärtan nära...

- Konvallerna

- Ninon

- På kvällen

- Serenad i Toledo (Serenadi Toledossa)

- Serenad (Serenadi)

- Tanke

- Tystnad

- Törnekronan (Piikkikruunu)

- Vattenplask Op. 11a No 2

- Återkomsten (Paluu)

Orchestral

- Prologue, op. 4

- Confessions, op. 5

- La dernière aventure de Pierrot, op. 6

- Le fétiche, op. 7

- Piano Concerto No. 1, op. 8 (1917)

- Hymne à la nuît, op. 9

- Danse macabre, op. 10

- Cinq sonettes pour l'orchestre de la chambre, op. 11

- Un chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, op. 12

- Mysterium, op. 13

- Flambeaux éteints, op. 14

- Chantecler, op. 15

- Le sacrifice, op. 17

- Symphony No. 1, op. 18 (1920)

- Symphony No. 2, op. 20 (1921)

- Le prophète, op. 21

- Piano Concerto No. 2, op. 22 (1921)

- Piano Concerto No. 3, op. 23 (1922)

- Symphony No. 3, op. 27 (1923-7)

- Cor ardens (1927)

- Narcissous (1930)

- Le chant de l’espace (1931/38)

- La flamme éternelle (1936)

- La face d’une grande ville (1936/37)

References

- Salmenhaara, Erkki. "Pingoud, Ernest". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Retrieved 28 February 2014. (subscription required)

- Salmenhaara, Erkki (1997). "Ernest Pingoud". Music Finland. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

(Originally published in Erkki Salmenhaara: Ernest Pingoud, 1997. ISBN 951-96274-7-2)

- Jurkowski, Edward (2005). "Alexander Scriabin's and Igor Stravinsky's Influence upon Early Twentieth-Century Finnish Music: The Octatonic Collection in the Music of Uuno Klami, Aarre Merikanto and Väinö Raitio". Intersections: Canadian Journal of Music. 25 (1–2): 67–85. doi:10.7202/1013306ar. ISSN 1911-0146. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- Häyrynen, Antti (1999). "The road to St. Petersburg". Finnish Musical Quarterly (4). Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- "[catalogue entry for ODE 875-2]". Ondine. Retrieved 28 February 2014.