Equidimensional

Equidimensional is an adjective applied to objects that have nearly the same size or spread in multiple directions. As a mathematical concept, it may be applied to objects that extend across any number of dimensions, such as equidimensional schemes. More specifically, it's also used to characterize the shape of three-dimensional solids.

In geology

The word equidimensional is sometimes used by geologists to describe the shape of three-dimensional objects. In that case it is a synonym for equant.[1] Deviations from equidimensional are used to classify the shape of convex objects like rocks or particles.[2] For instance Th. Zingg in 1935 pointed out[3] that if a, b and c are the long, intermediate, and short axes of a convex structure, and R is a number greater than one, then four mutually exclusive shape classes may be defined by:

Table 1: Zingg's convex object shape classes

| shape category | long & intermediate axes | intermediate & short axes | explanation | example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| equant | b < a < R b | c < b < R c | all dimensions are comparable | ball |

| prolate | a > R b | c < b < R c | one dimension is much longer | cigar |

| oblate | b < a < R b | b > R c | one dimension is much shorter | pancake |

| bladed | a > R b | b > R c | all dimensions are very different | belt |

For Zingg's applications, R was set equal to 3⁄2. Perhaps this is an intuitively reasonable setting in general for the point at which something's dimensions become significantly unequal.

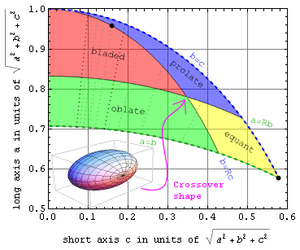

The relationship between the four categories is illustrated in the figure at right, which allows one to plot long and short axis dimensions for the convex envelope of any solid object. Perfectly equidimensional spheres plot in the lower right corner. Objects with equal short and intermediate axes lie on the upper bound, while objects with equal long and intermediate axes plot on the lower bound. The dotted gray and black lines correspond to integer a⁄c values ranging from 2 up to 10.

The point of intersection for all four classes on this plot occurs when the object's axes a:b:c have ratios of R2:R:1, or 9:6:4 when R=3⁄2. Make axis b any shorter and the object becomes prolate. Make axis b any longer and it becomes oblate. Bring a and c closer to b and the object becomes equidimensional. Separate a and c further from b and it becomes bladed.

For example, the convex envelope for some humans might plot near the black dot in the upper left of the figure.

See also

- Aspect ratio between long and short

- Equant as a noun used in astronomy

- Oblate spheroid

- Prolate spheroid

- shape analysis

Footnotes

- American Geological Institute Dictionary of Geological Terms (1976, Anchor Books, New York) p.147

- C. F. Royse (1970) An introduction to sediment analysis (Arizona State University Press, Tempe) 169pp.

- Th. Zingg (1935). "Beitrag zur Schotteranalyse". Schweizerische Mineralogische und Petrographische Mitteilungen 15, 39–140.