Epiphanius the Wise

Epiphanius the Wise (Russian: Епифаний Премудрый) (died 1420) was a monk from Rostov, hagiographer and disciple of Saint Sergius of Radonezh.[1] Historian Serge A. Zenkovsky wrote that Epiphanius, along with Stephen of Perm, along with St. Sergius of Radonezh, and the painter Andrei Rublev signified "the Russian spiritual and cultural revival of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century."[2]

Life

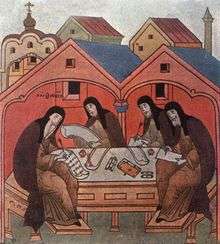

Epiphanius was born in Rostov in the first half of the fourteenth century. As a young man, he joined the monastery of Gregory the Theologian in Rostov. There he learned to copy manuscripts and paint icons. He would also have learned Greek and the Greek hagiographic traditions. Later he went to Trinity Monastery, a house founded by Sergius of Radonezh in 1337.[3]

Epiphanius travelled extensively, and is known to have visited Moscow, Constantinople and Mount Athos.[3]

Writing

Stephen of Perm had been a monk at Rostov; Sergii had founded Trinity monastery. Epiphanius wrote hagiographies of both St. Stephen of Perm and St. Sergius. The latter, Life of Our Holy and Godbearing Father Sergii Thaumaturgus, he started to write a year after the death of Saint Sergius according to his own memories, and his recollection of the accounts of other contemporaries. He finished the writings 26 years after the death of Sergius, i.e., around 1417-1418. There was a rewriting of the work by Pachomius the Serb (Пахомий Серб), which is usually more readily available.[4]

The Life of Sergii Radonezhsky follows well established hagiographical conventions, and contains a number of parallels to scriptural passages. His focus is on the saint's spiritual qualities and therefore does not dwell on his close ties to Prince Dmitry Donskoy. Epiphanius was interested in portraying an idealized account of sanctity, and did so through lengthy panegyrics. His literary style was given the name pletenie sloves, or "the weaving/braiding of words", and is marked by an abundance of neologisms, in which Epiphanius liked to form a large number of noun or adjective-noun combinations. The ordinary words of a common man "...are incapable of expressing the greatness of the deeds done by holy men to the glory of Christ."[5]

Serge Zenkovsky hails Epiphanius' writings as "a new page in Russian literary history".[6] It is often thought that Epiphanius' new style was influenced by the contemporary surge in Russian painting,[7] and it has been noted that Epiphanius was a great admirer of Theophanes the Greek.[8] A 1413 letter of Epiphanius, who knew Theophanes, to St. Cyril of Beloozero provides the principal source of information about the great icon painter.[9]

Works

- The Life of Sergii Radonezhsky, Житие преподобного Сергия

- Oration on the Life and Teaching of Our Holy Father Stephen, Former Bishop of Perm,

- Слово похвально преподобному отцу нашему Сергию

References

- Janet Martin, Medieval Russia, 980-1584, (Cambridge, 1995), p. 230

- Serge A. Zenkovsky, Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales, Revised Edition, (New York, 1974), p. 259

- "Epiphanius the Wise", Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature

- "Pachomius the Serb and his Autograph", The National Library of Russia

- "Epiphanius the Most Wise", A History of Russian Literature

- Serge A. Zenkovsky, Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales, Revised Edition, (New York, 1974), p. 259

- Janet Martin, op. cit., p. 232

- See, for instance, here

- Tsounis, Catherine. "What Was Theophanes of Constantinople’s Contribution to Early Russia?", Greek Reporter, October 25, 2015

- Sources

- Martin, Janet, Medieval Russia, 980-1584, (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 230, 232

- Zenkovsky, Serge A. (ed.), Medieval Russia's Epics, Chronicles, and Tales, Revised Edition, (New York, 1974), pp. 259–89