Enrique Ika

Enrique Ika a Tuʻu Hati (c. 1859 – after 1900) was elected ‘ariki (king) of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in 1900 and led a failed rebellion. He was one of the last Rapa Nui to claim the traditional kingship in the early 20th-century. However, he is generally not remembered as the last king instead his predecessor Riro Kāinga is generally regarded as the last king, although neither held much power.[note 1]

| Enrique Ika | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titular King of Rapa Nui | |||||

| Reign | 1900 | ||||

| Predecessor | Siméon Riro Kāinga | ||||

| Successor | Moisés Tuʻu Hereveri | ||||

| Born | Anakena | ||||

| Died | c. 1859 | ||||

| Burial | after 1900 | ||||

| Spouse | Anastasia Renga Hopuhopu to Tetono | ||||

| Issue | María ‘Aifiti Engepito Ika Tetono Victoria Veritahi Magdalena Ukahetu Margarita Uka Hipólito | ||||

| |||||

| Father | Hua ‘Anakena a Hatu’i | ||||

| Mother | Mata a Puhirangi | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

Biography

Enrique Ika a Tuʻu Hati was born c. 1859, at Anakena on the northern coast of Easter Island. His parents were Hua ‘Anakena a Hatu’i and Mata a Puhirangi. Oral tradition stated that Ika received the patronymic of Tuʻu Hati from an uncle. Considered an ariki paka or nobleman, he was a member of the Miru clan which the ‘ariki mau or traditional rulers of Easter Island belonged to. Ika married on 9 March 1879 to Renga Hopuhopu to Tetono (c. 1857–1942), baptized Anastasia, a woman from the Tupahotu clan. Their daughter was named María ‘Aifiti Engepito Ika Tetono, and she married Juan Tepano Rano, a Tupahotu clansman who accompanied King Siméon Riro Kāinga to Chile in 1898 and later became a cultural informant on Rapa Nui culture.[3] Their other children were Victoria Veritahi, Magdalena Ukahetu, Margarita Uka, and Hipólito.[4]

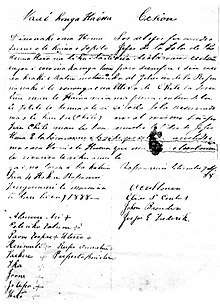

The penultimate King Atamu Tekena of Easter Island ceded the island to Chile (represented by Captain Policarpo Toro) on 9 September 1888. Ika was one of to'opae (advisors) to sign the agreement. However, the treaty of annexation was never ratified by Chile and Toro's colony failed. The Chilean government abandoned the settlement in 1892 due to political troubles on the mainland, which was embroiled in civil war, and this prompted the Rapa Nui to reassert their independence.[5][6]

After the 1892 death of Tekena, Siméon Riro Kāinga and Ika were candidates for the throne. Although both were of the Miru clan, Ika was more closely related to Kerekorio Manu Rangi, the last undisputed ‘ariki mau, who died during an outbreak of tuberculosis in 1867.[1] However, Kāinga's cousin Maria Angata Veri Tahi 'a Pengo Hare Kohou, a Catholic catechist and prophet, organized many of the island's women in his support. Riro was allegedly elected primarily because of his good looks and Angata's influence.[7][8] Ika was appointed as his prime minister.[9][10]

The Rapa Nui unsuccessfully attempted to reclaim indigenous sovereignty in the absence of direct Chilean control from 1892 to 1896. However, Chile reasserted its claim, and the island was later leased to Enrique Merlet and his ranching company. Alberto Sánchez Manterola was appointed Merlet's representative and also appointed Chile's maritime sub-delegate. They restricted the islanders' access to most of their land except a walled-off settlement at Hanga Roa, which they were not allowed to leave without permission. The young king attempted to protest the company's abuse but died under suspicious circumstances at Valparaíso.[11][12] News of the king's death did not reach the island until March 1899. Subsequently, Sánchez declared the native kingship abolished.[13][14] According to the accounts of Bienvenido de Estella, Sánchez declared to the islanders, "Ya no hay más rey en la isla. ¡Yo mando!" while Ika responded "No, todavía hay rey: yo lo soy"[15] Sánchez later wrote in 1921, “...desde que se supo la muerte del Rey puse mano firme para terminar con esta dinastía y creo haberlo conseguido porque no se habló más del sucesor de Riro Roco.”[16]

Riro Kāinga has been generally referred to as the last king of Easter Island. However, two other candidates for the kingship existed after him including Ika and Moisés Tuʻu Hereveri. When the news of Riro's death arrived in Easter Island, Prime Minister Ika was considered the natural successor. He was proclaimed king on 8 January 1900. He led an unsuccessful strike against Sánchez and the company. Ika's resistance became ineffective with the increased coercive power of the colonial authority and the company. In the end of March 1900, the schooner Maria Luisa brought Merlet and a dozen armed guardians to join the force of the company. Merlet. Restoring the so-called "pax merletiana", Merlet burned the Rapa Nui owned plantations to make them dependent on the company's grocery store. In May 1900, Chilean Naval corvette Baquedano under the command of Captain Arturo Wilson Navarrete brought back two Rapa Nui who had accompanied King Riro to the continent three years ago, Tepano and José Pirivato. Pirivato would later become a partisan of Ika and later Angata. The captain intended to deport any disruptors, but Sánchez felt confident enough to tell the captain that it was not necessary to deport anyone. The Rapa Nui complained about the mistreatment and low salaries with Captain Wilson through an interpreter (one of the Rapa Nui returning from the continent) although to no satisfactory results.[17][10][18][19]

In mid-November 1900, Sánchez was succeeded by Horacio Cooper White who was more despotic than his predecessor. Chilean shepherd Manuel A. Vega, who had married King Riro's widow Véronique Mahute, led a revolt in 1901. Ika's successor Hereveri led another unsuccessful indigenous rebellion from 1901 to 1902. In 1902, Chile appointed Ika's son-in-law Juan Tepano Rano as cacique in an attempt to end indigenous resistance. A decade later, Angata led another unsuccessful rebellion against the ranching company in 1914. Each revolts were crushed when the Chilean navy arrested the ringleaders of the revolt and exiled them to mainland Chile.[17][10][20]

The kingship remained vacant for a century after Ika and Hereveri. An independence movement has continued on the island.[21] In 2011, Riro Kāinga's grandson, Valentino Riroroko Tuki, declared himself king of Rapa Nui.[22][23]

See also

Notes

- Kerekorio Manu Rangi, the last undisputed ‘ariki mau, died during an outbreak of tuberculosis in 1867.[1][2] Although Riro Kāinga and his predecessor Atamu Tekena held the title of king, their power and legitimacy in comparison with their predecessors are doubted. Historian Alfred Métraux wrote,

Although the islanders of to-day speak of the late kings, Atamu Te Kena and Riroroko, as if they were really kings, informants make it clear that they had very little in common with the ariki of olden days. Their power was of an indefinite, dubious nature, and they seem to have enjoyed none of the prerogatives of former ariki. Perhaps their only claim to the title lay in their descent-line; both belonged to the Miru group. Possibly if native civilization had continued, they might have been true kings. Personal pretension, supported by Chilean officers who needed a responsible intermediary to deal with the population, might have contributed toward the restoration of power to this fictitious and ephemeral royalty.

References

- Fischer 2005, pp. 91–92, 99, 101, 147.

- Pakarati 2015a, pp. 4–5.

- Pakarati 2015a, pp. 9–10, 16.

- Hotus 1988, pp. 153, 215, 221.

- Gonschor 2008, pp. 66–70, 286–287.

- Pakarati 2015a, pp. 8–10.

- McCall 1997, pp. 115–116.

- Fischer 2005, p. 147.

- Pakarati 2015a, pp. 10, 14.

- Pakarati 2015b, pp. 3–14.

- Gonschor 2008, pp. 66–70.

- Fischer 2005, pp. 152–154.

- Gonschor 2008, p. 69.

- Pakarati 2015b, pp. 3–4.

- Pakarati 2015a, p. 14.

- Pakarati 2015b, p. 4.

- Pakarati 2015a, pp. 13–16.

- Simonetti, Marcelo (12 November 2011). "El último Rey de la Isla de Pascua". Enlace Mapuche Internacional. Archived from the original on 15 September 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Fischer 2005, p. 147, 154–155.

- Gonschor 2008, pp. 66–70; Fischer 2005, pp. 155, 166–172; Van Tilburg 2003, pp. 148–163; Delsing 2004, pp. 26–28; Cristino & Fuentes 2011, pp. 68–69, 71, 81–83, 140–142

- Gonschor 2008, pp. 126–132, 185–193.

- Simonetti, Marcelo (16 October 2011). "Los dominios del rey". La Tercera. Santiago. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

- Nelsen, Aaron (30 March 2012). "A Quest for Independence: Who Will Rule Easter Island's Stone Heads?". Time. New York City. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2017.

Bibliography

- Cristino, Claudio; Fuentes, Miguel (May 2011). La Compañia Explotadora de Isla de Pascua Patrimonio, Memoria e identidad en Rapa Nui (PDF). Rapa Nui: Ediciones Escaparate. ISBN 9789567827992. OCLC 1080351219.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delsing, Riet (May 2004). "Colonialism and Resistance in Rapa Nui" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Los Ocos, CA: The Easter Island Foundation. 18 (1): 24–30. OCLC 930607850.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fischer, Steven R. (2005). Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-245-4. OCLC 254147531.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gonschor, Lorenz Rudolf (August 2008). Law as a Tool of Oppression and Liberation: Institutional Histories and Perspectives on Political Independence in Hawaiʻi, Tahiti Nui/French Polynesia and Rapa Nui (PDF) (MA thesis). Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/20375. OCLC 798846333.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hotus, Alberto (1988). Te Mau hatu ʻo Rapa Nui. Santiago: Editorial Emisión. OCLC 123102513.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCall, Grant (September 1997). "Riro Rapu and Rapanui: Refoundations in Easter Island Colonial History" (PDF). Rapa Nui Journal. Los Ocos, CA: The Easter Island Foundation. 11 (3): 112–122. OCLC 197901224.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Métraux, Alfred (June 1937). "The Kings of Easter Island". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. Wellington: The Polynesian Society. 46 (2): 41–62. JSTOR 20702667. OCLC 6015249623.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pakarati, Cristián Moreno (2015) [2010]. Los últimos 'Ariki Mau y la evolución del poder político en Rapa Nui.

- Pakarati, Cristián Moreno (2015). Rebelión, Sumisión y Mediación en Rapa Nui (1896–1915).

- Van Tilburg, JoAnne (2003). Among Stone Giants: The Life of Katherine Routledge and Her Remarkable Expedition to Easter Island. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-0-7432-4480-0. OCLC 253375820.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Estella, Bienvenido de (1920). Los misterios de la Isla de Pascua. Santiago: Imprenta Cervantes.

- Vives Solar, J.I. (1920). El último rey de Rapa-Nui. Revista Sucesos 932.

| Titles in pretence | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Siméon Riro Kāinga |

King of Rapa Nui 1900 |

Vacant Title next held by Moisés Tuʻu Hereveri |