Emma Roberto Steiner

Emma Roberto Steiner (1856 – February 27, 1929) was an American composer and conductor. She was one of the first women in the United States to make a living from conducting, and did so at more than 6,000 performances during her lifetime. Her career spanned nearly five decades, from the 1870s, when she first began conducting for touring comic opera companies, until her death in 1929. In the early 1900s, she took a decade-long hiatus from her musical career to move to Alaska, where she was a prospector and traveler. Steiner wrote hundreds of musical pieces, including seven operas.

| Emma Roberto Steiner | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Baltimore |

| Occupation | Composer, conductor |

Biography

Steiner was born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1856. Her father, Colonel Frederick Steiner, was a Mexican War hero and her mother an accomplished pianist. Thus, she was exposed to music at a young age, composing songs by age 7 and a piano duet at 9. Others recognized her talents early, and even suggested to her father that he send her to Paris to study music, but her parents refused and did not encourage her to develop the talent. She nonetheless continued composing, starting on an opera at age 11, Aminaide, one scene of which was produced at the Peabody Conservatory, a prominent music school in Baltimore that Steiner was not able to attend.[1]

Music historians are unsure exactly how or when, but by the age of 21, Steiner had left her family behind to pursue her musical career. She moved to Chicago, where she became assistant music director at a small opera company. In the following years, she worked as a conductor for a series of touring light opera companies that performed Gilbert and Sullivan and other comic operas that were popular during that period. In 1889 and again in 1891, her opera Fleurette was produced to good reviews.[1] Steiner rose to further prominence when one of her compositions was performed at the 1893 Chicago World's Columbian Exhibition.[2] The next year, she conducted a performance of her own works in New York City by the well-respected Anton Seidl Orchestra.[1]

Despite a bout of pneumonia in 1896, Steiner continued to conduct, compose, and perform. Soon after the turn of the century, however, she experienced a series of tragedies. A 1902 warehouse fire in New York destroyed many of her works, including the only remaining copy of her first opera. She experienced another, more severe illness that affected her eyesight.[1] And in 1909, she filed a lawsuit after the death of her father, who had remarried after her mother's death and had written Steiner out of his will in preference to his stepdaughter.[3]

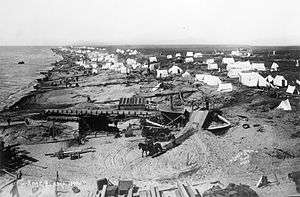

Around this time, Steiner left her career behind, and moved to Nome, Alaska. There, she became traveler and a prospector in the tin mining fields northwest of Nome, where she was the first white woman to enter, and where she discovered important tin deposits.[1] Following her return after nearly a decade, she became an advocate for Alaska, often giving talks about the state. She again turned to music, and continued writing and performing into the 1920s. The Metropolitan Opera held a special performance of her works in 1925, the last time a woman would conduct there until 1976. She also helped found a home for elderly and infirm musicians, to which she dedicated the proceeds of some of her later concerts. In its obituary after her death on February 27, 1929, The New York Times claimed that the stress of running the home had brought on the collapse that ended her life.[1]

During her career, Steiner conducted more than 6,000 performances of operas, operettas, and other works including a number of her own.[2] She wrote hundreds of musical pieces, including seven operas.[1] In addition to her original works she is credited along with Caroline B. Nichols as being among the first women in the United States to make a successful career out of conducting musical performances.[4]

References

- Ammer, Christine (2001). Unsung. Hal Leonard Corporation. pp. 196–200. ISBN 1-57467-061-1.

- Kramarae, Cheris; Spender, Dale. Routledge International Encyclopedia of Women, Vol. 3. Routledge. p. 1395. ISBN 0-415-92091-4.

- "ATTACKS COL. STEINER'S WILL; Miss Steiner Says His Stepdaughter Used Undue Influence". New York Times. March 8, 1909. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- Bowen, José Antonio, ed (2007). The Cambridge Companion to Conducting. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0-521-52791-0.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)