Emilio Ambasz

Emilio Ambasz is an architect and award-winning industrial designer. From 1969 to 1976 he was Curator of Design at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York. Ambasz was a precursor of 'green' architecture.[1]

Ambasz's trademark style is a combination of buildings and gardens, which he describes as 'green over grey'.[1] He bucked the trends of the 1970s, hiding his buildings under grass or putting them on boats.[1] The Emilio Ambasz Award for Green Architecture is awarded every year by the Architecture Israel Quarterly magazine.[2]

Born in Argentina (13 June 1943, Resistencia, Chaco), Ambasz is also a citizen of Spain by Royal Grant.[3] He studied at Princeton University where he completed the undergraduate program in one year[4] and earned, the next year, a master's degree in Architecture from the same institution. He served as Curator of Design at the Museum of Modern Art, in New York (1969–76), where he directed and installed numerous exhibits on architecture and industrial design, among them Italy: The New Domestic Landscape, in 1972; The Architecture of Luis Barragan, in 1974; and The Taxi Project, in 1976.

Ambasz was a two-term President of the Architectural League (1981–85). He taught at Princeton University's School of Architecture, and was visiting professor at the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm, Germany.

Among his architectural projects are the Grand Rapids Art Museum in Michigan, winner of the 1976 Progressive Architecture Award; a house for a couple in Cordoba, Spain, winner of the 1980 Progressive Architecture Award; and the Conservatory at the San Antonio Botanical Center in Texas, winner of the 1985 Progressive Architecture Award, the 1988 National Glass Association Award for Excellence in Commercial Design, and the 1990 Quaternario Award.

He also won the First Prize and Gold Medal in the competition to design the Master Plan for the Universal Exhibition of 1992, which took place in Seville, Spain, to celebrate the 500th anniversary of America's discovery.

The headquarters designed for the Financial Guaranty Insurance Company of New York won the Grand Prize of the 1987 International Interior Design Award of the United Kingdom, as well as the 1986 IDEA Award from the Industrial Designers Society of America. He won the First Prize in the 1986 competition for the Urban Plan for the Eschenheimer Tower in Frankfurt, Germany. His Banque Bruxelles Lambert in Lausanne, Switzerland, received the 1983 Annual Interiors Award.

Ambasz represented the United States at the 1976 Venice Biennale.[5]

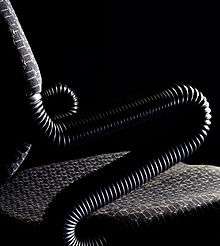

Since 1980 Ambasz has been the Chief Design Consultant for the Cummins Engine Co. He holds a number of industrial and mechanical design patents, and his Vertebrax chair is included in the Design Collections of the Museum of Modern Art[6] and the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[7] New York. The MOMA has also included in its Design Collection his 1967 3-D Poster Geigy Graphics and his Flashlight.[8]

Ambasz is the author of several books on architecture and design, among them Natural Architecture, Artificial Design, first published by Electa in 2001 and re-published four times since in expanded versions. "I detest writing theories. I prefer writing fables," he said in 2017.[9] Domus magazine has published some of those fables, including this one:

"Italy has remained a federation of city-states. There are museum-cities and factory-cities. There is a city whose streets are made of water, and another where all streets are hollowed walls. There is one city where all its inhabitants work on the manufacture of equipment for amusement parks; a second where everybody makes shoes; and a third where all its dwellers build baroque furniture. There are many cities where they still make a living by baking bread and bottling wine, and one where they continue to package faith and transact with guilt. Naturally, there is also one city inhabited solely by architects and designers. This city is laid out on a grid, its blocks are square, and each is totally occupied by a cubic building. Its wails are blind, without windows or doors.

The inhabitants of this city pride themselves on being radically different from each other. Visitors to the city claim, however, that all inhabitants have one common trait; they are all unhappy with the city they inherited and moreover, concur that it is possible to divide the citizens into several distinct groups. The members of one of the groups live inside the building blocks. Conscious of the impossibility of communicating with others, each of them, in the isolation of his own block, builds and demolishes every day, a new physical setting. To these constructions they sometimes give forms which they recover from their private memories; on other occasions, these constructs are intended to represent what they envision communal life may be on the outside.

Another group dwells in the streets. Both as individuals and as members of often conflicting sub-groups, they have one common goal: to destroy the blocks that define the streets. For that purpose they march along chanting invocations, or write on the walls words and symbols which they believe are endowed with the power to bring about their will. There is one group whose members sit on top of the buildings. There they await the emergence of the first blade of grass from the roof that will announce the arrival of the Millennium. As of late, rumors have been circulating that some members of the group dwelling in the streets have climbed up to the buildings’ roof-tops, hoping that from this vantage point they could be able to see whether the legendary people of the countryside have begun their much predicted march against the city, or whether they have opted to build a new city beyond the boundaries of the old one."

In the winter of 2011–12, Ambasz architectural, industrial, and graphic design work was exhibited at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, in a comprehensive major retrospective of his complete works.[10] In 2017, Lars Mueller Publishers issued a much improved version in English (Emerging Nature: Precursor of Architecture and Design) of the book issued on the occasion of that exhibition.

The American Institute of Architects admitted him to Honorary Fellowship in recognition of distinguished achievement in the profession of architecture in May 2007. He is also an Honorary International Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He is the sole recipient of the 2014 Medal of Science from The Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Bologna, Italy, and the first recipient of the Terra Madre Award.

Exhibitions Curated

- At Princeton University, he curated the exhibition Designing Programs/Programming Designs: An Exhibition of Karl Gerstner

- He curated at The Museum of Modern Art selected exhibitions such a:

- 1969 Paris: May 1968: Posters of the Student Revolt

- 1972 Italy: The New Domestic Landscape: Achievements and Problems of Italian Design

- 1973 A Classic Car: Cisitalia G1 1946

- 1974 The Architecture of Luis Barragan

- 1976 The Taxi Project: Realistic Solutions for Today

Exhibitions of works

- 1983 Emilio Ambasz: 10 Years of Architecture, Graphic and Industrial Design, a circulating show presented in Milan, Madrid, and Zurich

- 1985 Emilio Ambasz, The Axis Design and Architecture Gallery, Tokyo

- 1986 Emilio Ambasz, Institute of Contemporary Art of Geneva at HaIle Sud, Switzerland

- 1987 Emilio Ambasz, Arc-en- Ciel Gallery at the Center of Contemporary Art, Bordeaux, France

- 1989 Emilio Ambasz: Architecture, one-man show at The Museum of Modem Art, New York

- 1989 Emilio Ambasz: Architecture, Exhibition, Industrial and Graphic Design, a circulating one man show presented in San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art, the Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Montreal, the Akron Art Museum in Ohio, the Art Institute of Chicago in Illinois, and the Laumeier Sculpture Park in SI. Louis

- 1993 Emilio Ambasz, one-man show, Tokyo Station Contemporary Center, Japan

- 1994 Emilio Ambasz, Architecture and Design, one-man show at the Centro Cultural Arte Contemporáneo in Mexico City.

- 2009 In Situ:Architecture and Landscape, a group show at The Museum of Modern Art, New York

- 2010 Green over Gray, one-man show at the Grimaldi Forum, Monaco

- 2011-2012 Emilio Ambasz: Inventions – Architecture and Design; a comprehensive major retrospective, at the Centro Nacional de Arte Contemporáneo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain

Publications by Ambasz

- 1972 Ambasz, Emilio, ed.: Italy: The New Domestic Landscape: Achievements and Problems of Italian Design. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

- 1976 Ambasz, Emilio, ed.: The Taxi Project: Realistic Solutions for Today. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

- 1976 Ambasz, Emilio: The architecture of Luis Barragàn. The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Publications about Ambasz

- 1989 Emilio Ambasz: The Poetics of the Pragmatic: Architecture, Exhibit, Industrial and Graphic Design. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

- 1993 Emilio Ambasz: Jnventions: The Reality of the ldeal. New York: Rizzoli International Publications.

- 1999 Architettura e Natura: Emilio Ambasz – Progetti & Oggetti. Milan: Electa.

- 2001 Emilio Ambasz: Natural Architecture, Artificial Design. Milan: Electa.

- 2004 Emilio Ambasz: A Technological Arcadia, by Fulvio Irace. Milan: Skira

- 2005 Emilio Ambasz: Casa de Retiro Espiritual. Electa Mondadori

- 2016 Emilio Ambasz: Architecture & Nature/Design & Artifice. Milan: Electa Mondadori

- 2017 Emerging Nature - Emilio Ambasz: Precursor of Architecture and Design, Lars Muller Publishers, Zurich, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3-03778-526-3

Architectural Awards and Prizes

- 1976 Progressive Architecture Award for the Grand Rapids Art Museum, Michigan

- 1980 Progressive Architecture Award for La Casa de Retiro Spiritual, north of Seville, Spain

- 1983 Annual Interiors Award for the interior of Banque Bruxelles Lambert, Lausanne, Switzerland

- 1985 Progressive Architecture Award for Conservatory at the San Antonio Botanical Center, Texas

- 1986 First Prize and Gold Medal in the closed competition for the Universal Exhibition of 1992, Seville, Spain, plus special Architectural Projects Award for the Universal Exhibition of 1992, Seville, Spain

- 1986 First Prize in the competition for the Urban Pian for the Eschenheim Tower, Frankfurt, Germany

- 1987 Grand Prize of the International Interior Design Award for the headquarters of Financial Guaranty Insurance Company, New York

- 1988 National Glass Association Award for Excellence in Commercial Design for the Conservatory at the San Antonio Botanical Center, Texas

- 1990 Quaternario Award for the Conservatory at the San Antonio Botanical Center, Texas

- 2000 Special award by the Japanese Ministry of Public Works for the Mycal Cultural Center at Shin-Sanda, Japan

- 2000 Saflex Design Award for the Mycal Cultural Center at Shin-Sanda, Japan

- 2000 Architectural Grand Award by the American institute of Architects/Business Week for Fukuoka Prefectural and International Hall, Japan

- 2001 First Prize from the Japanese Institute of Architects for Fukuoka Prefectural and International Hall, Japan

- 2002 American Architectural Award for Monument Towers, Phoenix, Arizona,

- 2007 Medalla Manuel Tolsà by La Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico

- 2010 Honorary Fellowship at The American Institute of Architects

- 2013 Commendatore d'Italia, Stella d'Oro, by the Italian government

- 2014 ISA 2014 Medal for Science of the Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Bologna

- 2015 Honorary International Fellow at the Royal Institute of British Architects

Design Awards and Prizes

- 1977 GoId Prize by the IBD (USA) for the Vertebra Seating System

- 1979 SMAU Prize (Italy) for the Vertebra Seating System

- 1980 Design Excellence Award by the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) for Logotec spotlight range

- 1981 Compasso d'Oro (Italy) for the Vertebra Seating System

- 1983 Design Excellence Award by the IDSA for Oseris spotlight range

- 1984 Jury Special Award by the Tenth Biennial of Industrial Design, Ljubljana

- 1985 Annual Design Review Award from Industria! Design Society of America (IDSA) for Cummins N14 Engine

- 1986 Design Excellence Award by the iDSA for Escargot air filter design for Fleetguard Incorporated

- 1986 IDEA Award from the IDSA for the headquarters of Financial Guaranty Insurance Company of New York, New York

- 1987 Nominated for American Institute of Architects' Architectural Projects Award for the Mercedes Benz Showroom

- 1987 Industrial Excellence ward by the lDSA forSaturno modular Lighting system

- 1988 Nominated for Compasso d'Oro (Italy) and by the IDSA for Flashlight

- 1988 Industrial Excellence Award by the IDSA

- 1989 Designer's Choice Award for AquaColor water color set

- 1991 Compasso d'Oro (Italy) for Qualis seating design

- 1992 Award by the IDSA for Handkerchief Television, Sunstar Toothbrushes, and Soft Notebook

- 1997 Vitruvius Award by the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires

- 1999 Award for Design Excellence by the IDSA/Business Week for Cummins Signature 600 Engine

- 2000 Gold Award for Design Excellence by the IDSA/Business Week, for Saturno, a street Lighting system

- 2001 Compasso d'Oro (Italy), for Saturno

- 2003 Gold Award in iF Design Award by the International Forum for Design, for Stacker chair design

- 2014 Medal of Science from the Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Bologna, Italy

References

- LaBarre, Suzanne (September 13, 2009). "Green Over Gray". Metropolis Magazine. Archived from the original on 2013-01-08. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- 'Architecture Awards, Israel, 2010 : Buildings + Architects', e-architect.com. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- "BOE.es – Documento BOE-A-2003-17910". www.boe.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- "The Elusive Mr. Ambasz". Architect. 2009-07-31. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- Sennott, Stephen (2004-01-01). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781579584337.

- "Emilio Ambasz, Giancarlo Piretti. Vertebra Operational Chair. 1975 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ""Vertebra" Armchair | Emilio Ambasz, Giancarlo Piretti | 1989.48 | Work of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- "Emilio Ambasz. Flashlights. 1983 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- "Emilio Ambasz: "I Detest Writing Theories, I Prefer Writing Fables"". ArchDaily. 2017-01-24. Retrieved 2017-05-22.

- "Emilio Ambasz | Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía". www.museoreinasofia.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 2017-05-20.

- Pile, John F., ed.: "Ambasz, Emilio." The Grove Dictionary of Art, http://www.groveart.com/ (March, 2000).

- Rafael Ordóñez: Emilio Ambasz: un genio desconocido.

Further reading

- Mario Bellini, Alessandro Mendini, Michael Sorkin, Ettore Sottsass: Emilio Ambasz: The Poetics of the Pragmatic, Rizzoli, 1989

- Emilio Ambasz, Michael Sorkin: Analyzing Ambasz, The Monacelli Press, 2004

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emilio Ambasz. |