Emilianus-Stollen

The Emilianstollen is part of a Roman copper mine on the escarpment of the Saargau in the St. Barbara district of Wallerfangen in Saarland, Germany.

The entrance is about 150 metres (490 ft) from the main road. The ancient tunnel with its carved stone inscription is the only direct evidence of underground mining in Central Europe from Roman times. However, it is not the oldest underground mine in Central Europe. In the 5th millennium BC There was already underground mining of flint[1] and copper ores.[2] Guided tours of the mine are available.[3]

Inscription

The stone-carved Emilianus inscription[4] at the entrance to the tunnel reads:

INCEPTA OFFI-

CINA (A)EMILIANI

NONIS MART(IIS)

("The [mining] operation of Aemilianus began work on March 7.")

The inscription documents the mining rights under Roman mining law (lex metallis dicta), according to which operation had to be started within 25 days and was allowed to stand idle for no longer than half a year without the mining rights being forfeited. The law, which dates back to Emperor Hadrian and was partly recorded on tablets found at of Vipasca (Aljustrel) in Portugal, provided uniform regulation of mining in the provinces. The right to mine was to be documented by Occupatio, the posting of a tablet with the name of the owner and the date mining began. Usually wooden tablets were erected, which later fell into decay.

The inscription does not include a year; however, it is assumed that the mining occurred in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD.[5] An impression of the inscription can be seen in the Wallerfangen Historical Museum. The mining was probably less for copper than for the production of Wallerfanger Blue (de:Wallerfanger Blau) from azurite and malachite.

Excavations

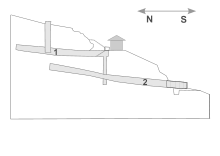

2) Lower Emilianusstollen

About 130 metres (140 yd) to the west is the Bruss tunnel, excavated in 1964, also of Roman origin. The medieval azurite mines on the Blaufels and the Limberg is attested by bills from 1492. The azurite mine was therefore continued around St. Barbara in post-Roman times.

In 1964 the first systematic excavations were carried out by the former Saarland Conservatory bureau. In the course of these investigations the Saarlouis district acquired the area and put the tunnels under monument protection. An excavation campaign carried out by the Bochum Mining Museum (de:Deutsches Bergbau-Museum Bochum) was completed in 1976 with the installation of a visitor mine, with the support of the Ensdorf Mine.

In 1993, the lower Emilianus tunnel was uncovered[6] and found in a condition untouched by subsequent mining. The Merchweiler mining company (de:Bergwerksgesellschaft Merchweiler) secured the tunnel from landslides with modern upgrades. Access is for research purposes only.

The investigations carried out by the Bochum Museum in 2008 revealed a much larger extension of the Bruss tunnel than was previously known. A shovel with a wooden handle and a broken blade was found and another shaft was discovered 20 metres (22 yd) before the end of the tunnel.[7]

References

- "Flint Mining in Prehistoric Europe". British Archaeological Reports International Series 1891. Oxford: P. Allard. 2008.

- Ch. Groer (2008). "Früher Kupferbergbau in Westeuropa". Universitätsforschungen zur Prähistorischen Archäologie 157. Bonn: Habelt.

- "Emilianusstollen Wallerfangen-Sankt Barbara".

- CIL XIII, 4238 = AE 1983, 717.

- "Forschungsgeschichte und Bedeutung (extract from the text Römischer Kupferbergbau in Deutschland: Neue Ausgrabungen am Emilianusstollen in St. Barbara (Saarland).". Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Universität Freiburg.

- "Römischer Kupferbergbau in Deutschland: Neue Ausgrabungen am Emilianusstollen in St. Barbara (Saarland)". Institut für Ur- und Frühgeschichte Universität Freiburg. Retrieved 14 Jul 2018.

- "Eine alte Schaufel überrascht Archäologen". Saarbrũcker Zeitung. Retrieved 14 Jul 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emilianusstollen. |

- Publications on the Emilianus-Stollen in Saarländischen Bibliographie

- "Azuritbergbau in Wallerfangen". Deutsches Bergbaumuseum. Retrieved 14 Jul 2018.