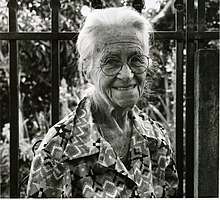

Emilia Prieto Tugores

Emilia Prieto Tugores (11 January 1902 – 1986) was a graphic artist, educator, singer, composer, and scholar of folklore from the Central Valley of Costa Rica, one of the few women to enter the field of artistic satire in the first half of the 20th century. Her work was recognized with a Joaquín Monge Prize for cultural periodism in the 1984. Studying her native folklore, Prieto's collection of songs "influenced [a] generation of troubadours".[1] The Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial Emilia Prieto Tugores was named for her, and awarded for the first time, in 2015.[2]

Biography

Born in San José, Costa Rica, on 11 January 1902, Prieto spent her childhood on the Guarari farm in the hills of Las Hiras, Heredia. She completed her high school education at El Colegio Superior de Señoritas, where she qualified as a schoolteacher in 1921. Prieto became an art teacher in various Costa Rican schools including Ramiro Aguilar School where she was principal. Prieto also taught at the Universidad Obrera or National Workers University. In 1922 she took painting classes at the Costa Rican School of Fine Arts (Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes).[3]

Prieto's art is characterized by a spirit of irreverence, as she poked fun at those who were critical of efforts towards social reform. She was herself an active feminist, a member of the Communist Party and the Costa Rican Women's Alliance (Alianza de Mujeres Costarricenses). From 1925 to 1945, Prieto published a number of graphically illustrated satirical essays, sometimes using a pen name. Attacking the conservative attitudes of the times, her drawing La perfecta casada (The Perfect Housewife) is a caricature of the image of a woman (Primera exposición centroamericana de artes plásticas, 1935.)[4] Many of her essays were published in periodicals such as Libertad, Nuestra Voz and Trabajo.[3]

In the 1920s, Prieto looked at the way in which Costa Rican carts and carriages were decorated with a view to encouraging interest and discussion. As a result, the first procession of carts was held on the Paseo Colón with an exhibition of decorated carts in 1935.[5] In the 1930s, she founded the Anti-Fascist League and was a supporter of women's rights. She established the School of Popular Culture and the Workers' University in 1943 and founded the National Committee of Partisans for Peace in 1949.[6] During the 1948 uprising, Prieto was persecuted for her political activism and relieved of her post as head of the Ramiro Aguilar School.[7] She served as president of the Partisans for Peace and attended several conferences in Mexico, Panama, and Sweden. As part of the women's pacifist movement after World War II Prieto worked toward promoting world peace, serving as a delegate at the Peace Conference of the Pacific Rim in Beijing for the Unión de Mujeres Costarricenses (Union of Costa Rican Women) which was led by Carmen Lyra.[3]

In 1974, Prieto released an album of collected folksongs on Indica Records and in 1976, she presented a series of essays in conferences accompanied by musician Juan F. Hernández. In 1978, she published a collection of folk stories and maxims, Romanzas ticomeseteñas (Costa Rican lovesongs). In 1984, Prieto received the Joaquín García Monge National Journalism Award and in 1992 she was recognized for her work in preserving traditional folk lore with the National Award of Traditional Popular Culture. Prieto was inducted into the Gallery of Women of the Instituto Nacional de la Mujer (National Institute of Women) in 2005 for her work on behalf of women's equality.[6]

References

- Shaw, Lauren E. (2013). Song and Social Change in Latin America. Lexington. p. 53. ISBN 9780739179499.

- Chavez, Fernando; Díaz Zeledón, Natalia. "Poeta Rónald Bonilla es el Premio Magón de Cultura 2015". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- "Emilia Prieto Tugores" (in Spanish). INAMU. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Prieto Tugores, Emilia" (in Spanish). SINABI. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- "Premios Nacionales" (in Spanish). Dircultura. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Sánchez Molina, Ana (3 April 2011). "El agudo lápiz de Emilia Prieto". La Nación (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Cubillo Paniagua, Ruth (2011). Mujeres ensayistas e intelectualidad de vanguardia en la Costa Rica de la primera mitad del siglo XX. Costa Rica: Editorial UCR. p. 106. ISBN 978-9968-46-281-5.