Elliott formula

The Elliott formula describes analytically, or with few adjustable parameters such as the dephasing constant, the light absorption or emission spectra of solids. It was originally derived by Roger James Elliott to describe linear absorption based on properties of a single electron–hole pair.[1] The analysis can be extended to a many-body investigation with full predictive powers when all parameters are computed microscopically using, e.g., the semiconductor Bloch equations (abbreviated as SBEs) or the semiconductor luminescence equations (abbreviated as SLEs).

Background

One of the most accurate theories of semiconductor absorption and photoluminescence is provided by the SBEs and SLEs, respectively. Both of them are systematically derived starting from the many-body/quantum-optical system Hamiltonian and fully describe the resulting quantum dynamics of optical and quantum-optical observables such as optical polarization (SBEs) and photoluminescence intensity (SLEs). All relevant many-body effects can be systematically included by using various techniques such as the cluster-expansion approach.

Both the SBEs and SLEs contain an identical homogeneous part driven either by a classical field (SBEs) or by a spontaneous-emission source (SLEs). This homogeneous part yields an eigenvalue problem that can be expressed through the generalized Wannier equation that can be solved analytically in special cases. In particular, the low-density Wannier equation is analogous to bound solutions of the hydrogen problem of quantum mechanics. These are often referred to as exciton solutions and they formally describe Coulombic binding by oppositely charged electrons and holes. The actual physical meaning of excitonic states is discussed further in connection with the SBEs and SLEs. The exciton eigenfunctions are denoted by where labels the exciton state with eigenenergy and is the crystal momentum of charge carriers in the solid.

These exciton eigenstates provide valuable insight to SBEs and SLEs, especially, when one analyses the linear semiconductor absorption spectrum or photoluminescence at steady-state conditions. One simply uses the constructed eigenstates to diagonalize the homogeneous parts of the SBEs and SLEs.[2] Under the steady-state conditions, the resulting equations can be solved analytically when one further approximates dephasing due to higher-order many-body effects. When such effects are fully included, one must resort to a numeric approach. After the exciton states are obtained, one can eventually express the linear absorption and steady-state photoluminescence analytically.

The same approach can be applied to compute absorption spectrum for fields that are in the terahertz (abbreviated as THz) range[3] of electromagnetic radiation. Since the THz-photon energy lies within the meV range, it is mostly resonant with the many-body states, not the interband transitions that are typically in the eV range. Technically, the THz investigations are an extension of the ordinary SBEs and/or involve solving the dynamics of two-particle correlations explicitly.[4] Like for the optical absorption and emission problem, one can diagonalize the homogeneous parts that emerge analytically with the help of the exciton eigenstates. Once the diagonalization is completed, one can then compute the THz absorption analytically.

All of these derivations rely on the steady-state conditions and the analytic knowledge of the exciton states. Furthermore, the effect of further many-body contributions, such as the excitation-induced dephasing, can be included microscopically[5] to the Wannier solver, which removes the need to introduce phenomenological dephasing constant, energy shifts, or screening of the Coulomb interaction.

Linear optical absorption

Linear absorption of broadband weak optical probe can then be expressed as

where is the probe-photon energy, is the oscillator strength of the exciton state , and is the dephasing constant associated with the exciton state . For a phenomenological description, can be used as a single fit parameter, i.e., . However, a full microscopic computation generally produces that depends on both exciton index and photon frequency. As a general tendency, increases for elevated while the dependence is often weak.

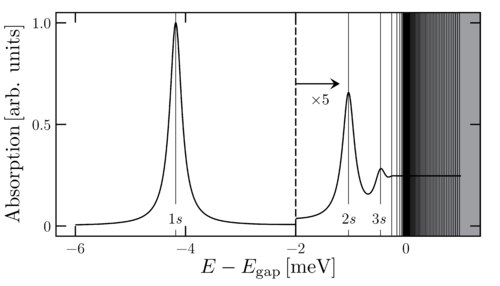

Each of the exciton resonances can produce a peak to the absorption spectrum when the photon energy matches with . For direct-gap semiconductors, the oscillator strength is proportional to the product of dipole-matrix element squared and that vanishes for all states except for those that are spherically symmetric. In other words, is nonvanishing only for the -like states, following the quantum-number convention of the hydrogen problem. Therefore, optical spectrum of direct-gap semiconductors produces an absorption resonance only for the -like state. The width of the resonance is determined by the corresponding dephasing constant.

In general, the exciton eigen energies consist of a series of bound states that emerge energetically well below the fundamental bandgap energy and a continuum of unbound states that appear for energies above the bandgap. Therefore, a typical semiconductor's low-density absorption spectrum shows a series of exciton resonances and then a continuum-absorption tail. For realistic situations, increases more rapidly than the exciton-state spacing so that one typically resolves only few lowest exciton resonances in actual experiments.

The concentration of charge carriers influence the shape of the absorption spectrum considerably. For high enough densities, all energies correspond to continuum states and some of the oscillators strengths may become negative-valued due to the Pauli-blocking effect. Physically, this can be understood as the elementary property of Fermions; if a given electronic state is already excited it cannot be excited a second time due to the Pauli exclusion among Fermions. Therefore, the corresponding electronic states can produce only photon emission that is seen as negative absorption, i.e., gain that is the prerequisite to realizing semiconductor lasers.

Even though one can understand the principal behavior of semiconductor absorption on the basis of the Elliott formula, detailed predictions of the exact , , and requires a full many-body computation already for moderate carrier densities.

Photoluminescence Elliott formula

After the semiconductor becomes electronically excited, the carrier system relaxes into a quasiequilibrium. At the same time, vacuum-field fluctuations[6] trigger spontaneous recombination of electrons and holes (electronic vacancies) via spontaneous emission of photons. At quasiequilibrium, this yields a steady-state photon flux emitted by the semiconductor. By starting from the SLEs, the steady-state photoluminescence (abbreviated as PL) can be cast into the form

that is very similar to the Elliott formula for the optical absorption. As a major difference, the numerator has a new contribution – the spontaneous-emission source

that contains electron and hole distributions and , respectively, where is the carrier momentum. Additionally, contains also a direct contribution from exciton populations that describes truly bound electron–hole pairs.

The term defines the probability to find an electron and a hole with same . Such a form is expected for a probability of two uncorrelated events to occur simultaneously at a desired value. Therefore, is the spontaneous-emission source originating from uncorrelated electron–hole plasma. The possibility to have truly correlated electron–hole pairs is defined by a two-particle exciton correlation ; the corresponding probability is directly proportional to the correlation. Nevertheless, both the presence of electron–hole plasma and excitons can equivalently induce the spontaneous emission. A further discussion of the relative weight and nature of plasma vs. exciton sources[7] is presented in connection with the SLEs.

Like for the absorption, a direct-gap semiconductor emits light only at the resonances corresponding to the -like states. As a typical trend, a quasiequilibrium emission is strongly peaked around the 1s resonance because is usually largest for the ground state. This emission peak often remains well below the fundamental bandgap energy even at the high excitations where all states are continuum states. This demonstrates that semiconductors are often subjects to massive Coulomb-induced renormalizations even when the system appears to have only electron–hole plasma states as emission resonances. To make an accurate prediction of the exact position and shape at elevated carrier densities, one must resort to the full SLEs.

Terahertz Elliott formula

As discussed above, it is often meaningful to tune the electromagnetic field to be resonant with the transitions between two many-body states. For example, one can follow how a bound exciton is excited from its 1s ground state to a 2p state. In several semiconductor systems, one needs THz fields to induce such transitions. By starting from a steady-state configuration of electron–hole correlations, the diagonalization of THz-induced dynamics yields a THz absorption spectrum[4]

In this notation, the diagonal contributions determine the population of excitons. The off-diagonal elements formally determine transition amplitudes between two exciton states and . For elevated densities, build up spontaneously and they describe correlated electron–hole plasma that is a state where electrons and holes move with respect to each other without forming bound pairs.[4]

In contrast to optical absorption and photoluminescence, THz absorption may involve all exciton states. This can be seen from the spectral response function

that contains the current-matrix elements between two exciton states. The unit vector is determined by the direction of the THz field. This leads to dipole selection rules among exciton states, in full analog to the atomic dipole selection rules. Each allowed transition produces a resonance in and the resonance width is determined by a dephasing constant that generally depends on exciton states involved and the THz frequency . The THz response also contains that stems from the decay constant of macroscopic THz currents.[4]

In contrast to optical and photoluminescence spectroscopy, THz absorption can directly measure the presence of exciton populations in full analogy to atomic spectroscopy.[9] For example, the presence of a pronounced 1s-to-2p resonance in THz absorption uniquely identifies the presence of excitons as detected experimentally in Ref.[10] As a major difference to atomic spectroscopy, semiconductor resonances contain a strong excitation-induced dephasing that produces much broader resonances than in atomic spectroscopy. In fact, one typically can resolve only one 1s-to-2p resonance because the dephasing constant is broader than energetic spacing of n-p and (n+1)-p states making 1s-to-n-p and 1s-to-(n+1)p resonances merge into one asymmetric tail.

See also

- Absorption

- Semiconductor-luminescence equations

- Semiconductor Bloch equations

- Quantum-optical spectroscopy

- Wannier equation

- Photoluminescence

- Terahertz technology

Further reading

- Haug, H.; Koch, S. W. (2009). Quantum Theory of the Optical and Electronic Properties of Semiconductors (5th ed.). World Scientific. p. 216. ISBN 978-9812838841.

- Ashcroft, Neil W.; Mermin, N. David (1976). Solid State Physics. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 978-0-03-083993-1.

- Kira, M.; Koch, S. W. (2011). Semiconductor Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521875097.

- Klingshirn, C. F. (2006). Semiconductor Optics. Springer. ISBN 978-3540383451.

- Kalt, H.; Hetterich, M. (2004). Optics of Semiconductors and Their Nanostructures. Springer. ISBN 978-3540383451.

References

- Kuper, C. G.; Whitfield, G. D. (1963). Polarons and Excitons. Plenum Press. LCCN 63021217.

- Kira, M.; Koch, S. W. (2011). Semiconductor Quantum Optics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521875097.

- Lee, Y.-S. (2009). Principles of Terahertz Science and Technology. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-09540-0. ISBN 978-0-387-09539-4.

- Kira, M.; Koch, S.W. (2006). "Many-body correlations and excitonic effects in semiconductor spectroscopy". Progress in Quantum Electronics 30 (5): 155–296. doi:10.1016/j.pquantelec.2006.12.002

- Jahnke, F.; Kira, M.; Koch, S. W.; Tai, K. (1996). "Excitonic Nonlinearities of Semiconductor Microcavities in the Nonperturbative Regime". Physical Review Letters 77 (26): 5257–5260. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.77.5257

- Walls, D. F.; Milburn, G. J. (2008). Quantum Optics (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-3-540-28574-8.

- Chatterjee, S.; Ell, C.; Mosor, S.; Khitrova, G.; Gibbs, H.; Hoyer, W.; Kira, M.; Koch, S.; Prineas, J.; Stolz, H. (2004). "Excitonic Photoluminescence in Semiconductor Quantum Wells: Plasma versus Excitons". Physical Review Letters 92 (6). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.067402

- Kira, M.; Hoyer, W.; Stroucken, T.; Koch, S. (2001). "Exciton Formation in Semiconductors and the Influence of a Photonic Environment". Physical Review Letters 87 (17). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.176401

- Kaindl, R. A.; Carnahan, M. A.; Hägele, D.; Lövenich, R.; Chemla, D. S. (2003). "Ultrafast terahertz probes of transient conducting and insulating phases in an electron–hole gas". Nature 423 (6941): 734–738. doi:10.1038/nature01676