Elizabeth Pinchard

Elizabeth Pinchard née Sibthorpe (fl. 1791 – 1820), was an English writer of children's fiction whose stories incorporated moral lessons aimed at older girls. She was recognised above all for The Blind Child, her first and most successful novel.

Writing

Pinchard’s children’s books were "didactic".[1] She admired the writers Barbauld and Genlis, who put education ahead of fantasy, and she aspired to emulate their work.[2] In her preface to The Blind Child, or Anecdotes of the Wyndham Family (1791) she outlined her hopes to "awaken in the rising generation" a "lively wish for goodness".[2] In this particular novel she emphasised that "excessive softness of heart" is not "true sensibility".[2][3] After the novel’s blind heroine has her sight restored by surgery, the doctor praises her sister for not showing "exaggerated feeling", and her mother adds that true sensibility is better than "false tenderness".[4]

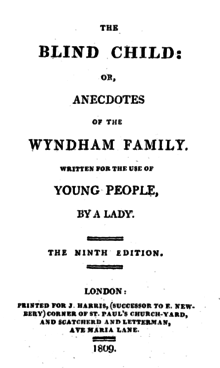

The Blind Child was republished often over the next twenty years, both in England and in North America. Its anonymous title page said it was "by a lady", while subsequent books usually announced they were "by the author of The Blind Child". It has continued to be her best-known work.[5] In between narrative sections, conversations were written out as simple dialogues between named speakers. Pinchard’s next publication was Dramatic Dialogues (1792), where the seven tales look like plays. Encouraging girls to perform theatrical works was frowned on by many, and Pinchard justified her use of dialogue, with occasional "stage" directions, by saying she thought it was easier to captivate young people with stories told without the repeated use of phrases like 'she said', 'she replied' etc.[6]

Her continuing interest in moral education for the young was clear on the title page of The Two Cousins (1794) which was presented as "a moral story for the use of young persons in which is exemplified the necessity of moderation and justice to the attainment of happiness."

Pinchard's other fiction included the Ward of Delamere, Family Affection: a tale for youth, Mystery and Confidence, and The Young Countess, which appeared in 1820. A review at that time complimented "all the productions" of the author, saying they had been praised by children's writer, critic and educational reformer Sarah Trimmer. Their value lay in the "especial solicitude of the author to inculcate the necessity of an undeviating regard to habits of piety, as the safest guarantee of a virtuous reputation"[7]

Personal life

The writer was married to John Pinchard, a lawyer in Taunton, Somerset.[1]

Books available online

References

- Turner, Living by the Pen: Women Writers in the Eighteenth Century, Routledge 2002

- Pinchard's preface to The Blind Child, 1791

- Bator ed., Masterworks of Children's Literature: c.1740-c.1836, Stonehill 1984, p47

- The Blind Child, 1791

- Zipes ed., Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature, OUP 2006

- Grenby, The Child Reader, 1700-1840, Cambridge 2011

- Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser, 8 March 1820