Elizabeth Langhorne Lewis

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis (9 December 1851–30 January 1946) was the founder of the Lynchburg Equal Suffrage League and vice-president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia.[1] She was also one of the founders of the Virginia League of Women Voters.[1]

Elizabeth Langhorne Lewis | |

|---|---|

| Born | December 9, 1851 Botetourt County, Virginia |

| Died | January 30, 1946 (aged 94) Lynchburg, Virginia |

| Nationality | U.S. |

| Known for | Women's Suffrage Campaigner |

Early Life

Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne was born in 1851 in Botetourt County, Virginia. As a child, she lived in Lynchburg.[1] She went to private schools in Lynchburg and Charlottesville. As a young woman, she taught in a number of schools in the Lynchburg area. In August 1873 she married John Henry Lewis. He was a civil war veteran and an attorney. Lewis was elected president of the Lynchburg Women's Club twice. She was an accomplished pianist and was active in the Lynchburg artistic community.[1]

Suffrage Activity

Lewis was the founder and president of the Lynchburg Equal Suffrage League.[1] The group, founded in October 1910, created petitions in support of women's suffrage addressed to the Virginia General Assembly and gave presentations to local groups. The group also published the Lynchburg Woman's Suffrage News in April 1917, printing 5,000 copies.

In December 1911, Lewis was elected vice-president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia and served in that role until the league dissolved after the passage of the 19th amendment.[1]

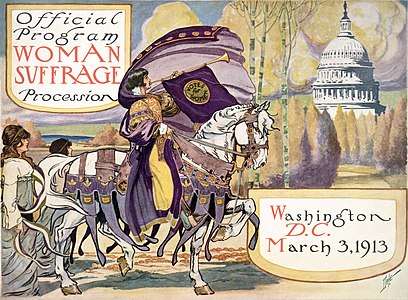

In March, 1913, Lewis helped to carry Virginia's banner in the Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, DC, the first large organized march on Washington for political purposes.[1][2] In October 1913, the annual meeting of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia was organized by the Lynchburg Equal Suffrage League.[1]

Lewis wrote an article for Virginia Suffrage News, published in November 1914.[1] In it, she wrote "that the woman's qualification for citizenship is as valid as the man's—that her identity of interest, her intelligence, her morality, her patriotism and her proven efficiency" entitled women to all the rights and responsibilities of citizenship for which "equal suffrage is an indispensable element."

Lewis presented numerous speeches about suffrage in Southern Virginia in 1915 and 1916, organizing a number of suffrage leagues in the cities where she spoke.[1] During this time, the league was undergoing rapid growth. In 1914, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia had 45 local chapters. In 1916, there were 115 chapters.[3] In 1915, she represented Lila Valentine at a national suffrage convention.[4]

In 1916, Lewis and her daughter Elizabeth Otey helped to persuade the Virginia Republican Party state convention to endorse women's suffrage.[4] On 2 October 1916, she debated Congressman Henry DeLaWarr Flood in Appomatox County. Flood was against extending the vote to women and was an influential voice within the Virginia Democratic Party. After Virginia declined to pass a state-level suffrage amendment in 1916, Lewis focused on lobbying Virginia's congressional delegation in support of a federal constitutional amendment, known as the Susan B. Anthony amendment. She picketed the White House in 1917, accompanied by her daughter Elizabeth Otey. The group's banner read "Kaiser Wilson, have you forgotten your sympathy with the poor Germans because they were not self-governed? 20,000,000 American women are not self-governed. Take the beam out of your own eye." It was snatched away as the march began.[4][2][5]

In the spring of 1918, her cousin Lila Valentine, the president of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia had a serious operation.[6] Lewis took over the running of the league.[1]

League of Women Voters

The Equal Suffrage League of Virginia disbanded on November 8, 1920, and the Virginia League of Women Voters was organized two days later at the state capitol.[7] Lewis was elected to the first board of directors.[1] In 1926-27, she was president of the state league.[1] She was president of the Lynchburg chapter of the league for more than a decade after it was formed in 1920.[1]

Death

Lewis died in Lynchburg on 30 January 1946. She was 94 years old. Her remains were buried next to those of her husband.[1][8]

References

- Tarter, Brent (2018). ""Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis (1851–1946)" Dictionary of Virginia Biography". Library of Virginia.

- "We the Women: after a century of the 19th amendment the Lynchburg Museum honors a movement". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Woman Suffrage in Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Tarter, Brent. ""Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis Otey (1880–1974)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography". Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- McArdle, Terence. "'Night of terror': The suffragists who were beaten and tortured for seeking the vote". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Tarter, Brent. ""Lila Hardaway Meade Valentine (1865–1921)," Dictionary of Virginia Biography". Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Organization of the Virginia League of Women Voters, November 10, 1920". Library of Virginia. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- "Elizabeth Dabney Langhorne Lewis (1851-1946) -..." www.findagrave.com. Retrieved 2020-05-27.