Elijah McCoy

Elijah J. McCoy (May 2, 1844 [2] – October 10, 1929) was a Canadian-born inventor and engineer of African American descent who was notable for his 57 US patents, most having to do with the lubrication of steam engines. Born free in Canada, he came to the United States as a young child when his family returned in 1847, becoming a U.S. resident and citizen.

Elijah McCoy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | May 2, 1844 Colchester, Ontario, Canada[1] |

| Died | October 10, 1929 (aged 85) |

| Resting place | Detroit Memorial Park East in Warren, Michigan, U.S. |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Occupation | Engineer, inventor, initially employed as a railroad fireman and oiler |

| Employer | Mine Coaling |

| Known for | Inventions |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Elizabeth Stewart; Mary Eleanor Delaney |

Early life

Elijah McCoy was born free in 1844 in Colchester, Ontario, Canada to George and Mildred (Goins) McCoy. At the time, they were fugitive slaves who had escaped from Kentucky to Canada via helpers through the Underground Railroad.[3] George and Mildred arrived in Colchester Township, Essex, Ontario Canada in 1837 via Detroit. Elijah McCoy had 11 siblings. Ten of the children were born in Canada from Alfred (1839) to William (1859). Based on 1860 Tax Assessment Rolls, land deeds of sale, and the 1870 USA Census it can be determined the George McCoy family moved to Ypsilanti, Michigan in 1859–60.

Elijah McCoy was educated in black schools of Colchester Township due to the 1850 Common Schools act which segregated the Upper Canadian schools in 1850. At age 15, in 1859, Elijah McCoy was sent to Edinburgh, Scotland for an apprenticeship and study. After some years, he was certified in Scotland as a mechanical engineer. By the time he returned, the George McCoy family had established themselves on the farm of John and Maryann Starkweather in Ypsilanti. George used his skills as a tobacconist to establish a tobacco and cigar business.

Career

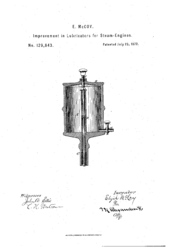

When Elijah McCoy arrived in Michigan, he could find work only as a fireman and oiler at the Michigan Central Railroad. In a home-based machine shop in Ypsilanti, Michigan, McCoy also did more highly skilled work, such as developing improvements and inventions. He invented an automatic lubricator for oiling the steam engines of locomotives and ships, patenting it in 1872 as "Improvement in Lubricators for Steam-Engines" (U.S. Patent 129,843).

Similar automatic oilers had been patented previously; one is the displacement lubricator, which had already attained widespread use and whose technological descendants continued to be widely used into the 20th century. Lubricators were a boon for railroads, as they enabled trains to run faster and more profitably with less need to stop for lubrication and maintenance.[4]

McCoy continued to refine his devices and design new ones; 50 of his patents dealt with lubricating systems. After the turn of the century, he attracted notice among his black contemporaries. Booker T. Washington in Story of the Negro (1909) recognized him as having produced more patents than any other black inventor up to that time. This creativity gave McCoy an honored status in the black community that has persisted to this day. He continued to invent until late in life, obtaining as many as 57 patents; most related to lubrication but others also included a folding ironing board and a lawn sprinkler. Lacking the capital with which to manufacture his lubricators in large numbers, he usually assigned his patent rights to his employers or sold them to investors. Lubricators with the McCoy name were not manufactured until 1920, near the end of his career, when he formed the Elijah McCoy Manufacturing Company to produce them.[4]

Historians have not agreed on the importance of McCoy's contribution to the field of lubrication. He is credited in some biographical sketches with revolutionizing the railroad or machine industries with his devices. Early twentieth-century lubrication literature barely mentions him; for example, his name is absent from E. L. Ahrons' Lubrication of Locomotives (1922), which does identify several other early pioneers and companies of the field.

Regarding the phrase "The real McCoy"

This popular expression, typically meaning the real thing, has been incorrectly attributed to Elijah McCoy's oil-drip cup invention. One theory is that railroad engineers looking to avoid inferior copies would request it by name,[5] and inquire if a locomotive was fitted with "the real McCoy system".[6][7] This theory is mentioned in Elijah McCoy's biography at the National Inventors Hall of Fame.[8] It can be traced to the December 1966 issue of Ebony in an advertisement for Old Taylor bourbon whiskey: "But the most famous legacy McCoy left his country was his name."[9] A 1985 pamphlet printed by the Empak Publishing Company also notes the phrase's origin but does not elaborate.[10]

Other possibilities for its origin have been proposed[4] and while it has undoubtedly been applied as an epithet to many other McCoys, its association with Elijah has become iconic[11] and remains topical.[12][13]

The expression, "The real McCoy", was first published in Canada in 1881, but the expression, "The Real McKay", can be traced to Scottish advertising in 1856.

In James S. Bond's The Rise and Fall of the "Union Club": or, Boy Life in Canada (1881), a character says, "By jingo! yes; so it will be. It's the 'real McCoy,' as Jim Hicks says. Nobody but a devil can find us there."[14]

Marriage and family

McCoy married Ann Elizabeth Stewart in 1868; she died four years later. He married for the second time in 1873 to Mary Eleanor Delaney. The couple moved to Detroit when McCoy found work there. Mary McCoy (died 1922) helped found the Phillis Wheatley Home for Aged Colored Men in 1898.[15] Elijah McCoy died in the Eloise Infirmary in Nankin Township, now Westland, Michigan, on October 10, 1929, at the age of 85, after suffering injuries from a car accident seven years earlier in which his wife Mary died.[16] He is buried in Detroit Memorial Park East in Warren, Michigan.[17]

In popular culture

- 1966, an ad for Old Taylor bourbon cited Elijah McCoy with a photo and the expression "the real McCoy", ending with the tag line, "But the most famous legacy McCoy left his country was his name."[18]

- 2006, Canadian playwright Andrew Moodie's The Real McCoy portrayed McCoy's life, the challenges he faced as an African American, and the development of his inventions. It was first produced in Toronto[7] and has also been produced in the United States, for example in Saint Louis, Missouri, in 2011, where it was performed by the Black Rep Theatre.

- In her novel Noughts & Crosses, Malorie Blackman describes a racial dystopia in which the roles of black and white people are reversed; Elijah McCoy is among the black scientists, inventors, and pioneers mentioned in a history class that Blackman "never learned about in school".[19]

Legacy

- 1974, the state of Michigan put an historical marker (P25170) at the McCoys' former home at 5720 Lincoln Avenue,[20] and at his gravesite.[21]

- 1975, Detroit celebrated Elijah McCoy Day by placing a historic marker at the site of his home. The city also named a nearby street for him.[22]

- 1994, Michigan installed a historical marker (S0642) at his first workshop in Ypsilanti, Michigan.[20]

- 2001, McCoy was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in Alexandria, Virginia.[8]

- 2012, the Elijah J. McCoy Midwest Regional U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (the first USPTO satellite office) was opened in Detroit, Michigan.[23][24][25][upper-alpha 1]

References

Notes

- "And the people of Detroit have time and again been they very sort of pioneers who shape our country with innovative audacity. Near the end of the 19th century, an inventor named Elijah McCoy came to this city, drawn by its potential, and history was made-with more than 57 U.S. patents by the end of his remarkable life, Elijah's vision transformed the railroad system, and with it our trade economy. That's the story of American possibility, realized through the power of the American patent-and I can think of no more fitting name to adorn the walls of this new office than the "Real McCoy" himself."[26]

Citations

- "Elijah McCoy Picture". Argot Language Center. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19.

- Sources give his birthdate as May 2, 1843; May 2, 1844; or less commonly March 27, 1843.

- Marshall, Albert (1989). The "real McCoy" of Ypsilanti. Ypsilanti, MI: Marland Pub.

- "The not-so-real McCoy". Brinkster. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved February 3, 2011. disputes "Real McCoy" story

- "Elijah McCoy, Inventor of the Week". Lemelson-MIT Program. May 1996. Archived from the original on 2003-08-23. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- Quinion, Michael. "The Real McCoy". World Wide Words.

- Casselman, William Gordon (2006). "The Real McCoy". Bill Casselman’s Canadian Word of the Day. Archived from the original on April 27, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- "Elijah McCoy, inventor profile". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 2008-12-28.

- Ebony, December 1966. p. 157. Archived January 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Bennetta, William J. "Did Somebody Say McTrash?". The Textbook League.

- Boyd, Herb (2017). Black Detroit: A People's History of Self-Determination. Amistad. p. 420. ISBN 978-0062346629.

- Lester Graham (2017-07-21). Stateside (Radio broadcast). Michigan Radio. Event occurs at 7:40. Retrieved 2017-07-22. Lay summary. First mention by Boyd at 6:40 minutes in.

- Boyd, Herb (2017). Black Detroit: A People's History of Self-Determination. Amistad. p. X. ISBN 978-0062346629.

- Bond, James S. The rise and fall of the "Union club": or, Boy life in Canada. Yorkville, Ontario. p. 1

- Baulch, Vivian M. (1995-11-26). "How Detroit got its first black hospital". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on 2012-07-10.

- Bellis, Mary. "Biography of Elijah McCoy, American Inventor". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 2019-09-02.

- Black Americans 17Th Century to 21St Century: Black Struggles and Successes

- Ebony Archived January 24, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, December 1966. p. 157

- Blackman, Malorie, Noughts & Crosses, New York: Random House, 2001.

- "Elijah McCoy". MichMarkers.com - The Michigan Historical Marker Web Site.

- "Detroit Memorial Park Cemetery". MichMarkers.com - The Michigan Historical Marker Web Site.

- "Elijah McCoy Home Informational Site". Detroit - The History and Future of the Motor City. University of Michigan.

- "Midwest Regional U.S. Patent and Trademark Office". USPTO. Retrieved May 2, 2017.

- Anders, Melissa (July 13, 2012). "Detroit beats Silicon Valley in opening first-ever patent office outside Washington, D.C." MLive Media Group. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- Markowitz, Eric (March 1, 2012). "What Does a Patent Office Mean For Detroit?". Inc. Retrieved July 10, 2012.

- Kappos, David (July 13, 2012). "Remarks to Open Elijah J. McCoy USPTO Detroit Location". USPTO. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

Further reading

- Haber, Louis (2007). Black Pioneers of Science and Invention. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich/Louis Haber Books. ISBN 0-15-208566-1. ISBN 978-0-15-208566-7.

- Haskins, James (1991). Outward Dreams: Black Inventors and Their Inventions. New York: Walker. ISBN 978-0-8027-6993-0.

- Hayden, Robert C. (1997). Nine Black American Inventors. 21st Century. pp. 171. ISBN 0-8050-2133-7. ISBN 978-0-8050-2133-2

- Klein, Aaron E. (October 1971). The Hidden Contributors: Black Scientists and Inventors in America. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-00641-1. ISBN 978-0-385-00641-5

- Moodie, Andrew (2006). The real McCoy. Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press. ISBN 978-0-88754-902-1.

- Sullivan, Otha; Haskins, James (April 21, 1998). Black Stars: African American Inventors. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 0-471-14804-0. ISBN 978-0-471-14804-3

- Towle, Wendy; Wil, Clay (Illustrator) (1993). The Real McCoy: The Life of an African American Inventor. A Blue Ribbon Book. Scholastic. ISBN 0-590-46134-6.

External links

- Elijah McCoy photos, Argot language center

- Elijah McCoy at Find a Grave

- "Elijah McCoy", National Inventors Hall of Fame