Eleonora de Cisneros

Eleonora de Cisneros (October 31, 1878 – February 3, 1934), was an American opera singer. Cisneros was a major backer towards the sale of Liberty bonds during World War I. She was a singer for the Metropolitan Opera company. Cisneros toured the United States during World War I singing in plays to raise funds for the Red Cross.

Eleonora de Cisneros | |

|---|---|

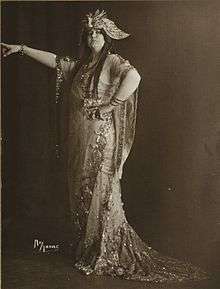

Cisneros in 1919 | |

| Born | Eleanor Broadfoot October 31, 1878 Manhattan, New York City |

| Died | February 3, 1934 (aged 55) Manhattan, New York City |

| Occupation | Opera singer |

| Parent(s) | John C. Broadfoot, Ellen Small |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life

Cisneros was born Eleanor Broadfoot in Manhattan, New York City on October 31, 1878 (some sources say November 1, 1878[1]). Her parents were John C. Broadfoot, a New York City clerk, and Ellen Small. She was an only child. Her father was of Scottish and her mother of Irish descent. She received her primary schooling at St. Agnes Seminary in Brooklyn. Cisneros started her initial singing studies in the United States under the American opera singers Adelina Murio-Celli d'Elpeux and Francesco Fanciulli. She became a mezzo-soprano opera singer.[2][3][4]

Mid life

The opera singer Jean de Reszke introduced Cisneros, then known as "Eleanor Broadfoot", to the manager of the Metropolitan Opera company in 1899 and she was hired.[5] Cisneros was the first American trained opera singer the Metropolitan Opera company hired.[2][3] Previous to this, the opera house would only hire singers formally trained in Europe.[6] She gave her first performance with the Metropolitan Opera company in Chicago on November 24, 1899.[4] Her role was as Rossweise in Die Walküre.[7] She performed the same role in New York City on January 5, 1900 – being her debut in that city.[7] After performing in New York City she then went to Philadelphia in a hurry and filled in as a contralto, with no rehearsal, in Il trovatore by Giuseppe Verdi at the Metropolitan Opera.[8] The manager of the opera company complimented Cisneros on her successful performance and she became a key singer.[8] Cisneros became their key contralto singer from 1906 -1911.[1]

Cisneros married Count Francois de Cisneros, a Cuban journalist, in 1901, becoming Countess Eleonora de Cisneros. She then went to Turin, Italy, in 1902 to perform. The Italians were not receptive to the "American" Eleanor Broadfoot from the Metropolitan Opera unless she paid a fee.[8] She had her business cards reprinted with her married name Countess Eleonora de Cisneros and she was well received then.[9] Cisneros made her début at Turin as Amneris in Giuseppe Verdi's opera Aida.[9] Cisneros debuted in 1906 at La Scala in Milan, Italy.[3] At this opera house in this year she established the part of Candia della Leonessa in the opera La figlia di Iorio by Alberto Franchetti.[10] She sang also the same year in the opera house the first performances of the operas The Queen of Spades by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Salome by Richard Strauss.[5] She also sang in the same opera house the first performance of the opera Elektra by Strauss, performed in 1909.[10]

Cisneros performed in Australia, Europe, Cuba, New Zealand and the United States. She was a performer at the Royal Opera House in London from time to time in 1904 to 1906.[10] After her initial European tour Oscar Hammerstein had her come back to New York City to perform at the Manhattan Opera House, where she sang for two seasons from 1906 to 1908 as a key singer.[10][11] Cisneros performed in dozens of opera roles in the Italian cities of Trieste, Ferrara, La Spezia, Milan, Modena, and Turin.[12] Cisneros sang in her mezzo-soprano opera voice the roles of Brünnhilde, Ortrud, Venus, Delilah, and Amneris.[10] Australian opera singer Nellie Melba declared that Cisneros performed the greatest Delilah in the world.[9] Melba had Cisneros perform in her own opera company in 1911 touring Australia and England, singing various opera roles.[5][9] In the following years Cisneros performed at the São Carlos National Theatre in Lisbon, Portugal, the Teatro Municipal theatre in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the Vienna State Opera in Vienna, the Bolshoi Kamenny Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Russia, and the Waldorf Theatre and Covent Garden in London, England. During her time in the United States she also performed many times for the Chicago-Philadelphia Opera Company.[3][5][10][13]

Later life

She was chairperson of the Artist and Musical Committee of the New York Catholic War Fund's Women's Committee during World War I.[7] Her career was hurt after making opera singing tours for the benefit of the war endeavors.[5][11] In the 1920s Cisneros performed mostly in Europe. While in Europe she lived in Paris until 1929.[13] After that she became a singing teacher in New York City until she retired.[13]

Death

She died of an epithelioma in Manhattan, New York City on February 3, 1934.[7] The Roman Catholic Church of St. Paul the Apostle in New York City conducted funeral services for her. She is buried at Calvary Cemetery in Long Island City, New York.[7]

Legacy

Listeners of Cisneros remember her wide vocal range of "G" to "C" and high volume contralto voice.[3][13] Cisneros had a large physical statuesque stage presentation.[5][10] She stood at 6 feet 2 inches and presented a queenly majestic appearance, which was ideal for her performances representing heroes.[10] With her mezzo-soprano opera voice she sang difficult roles like that of Santuzza, Gioconda, Kundry, Carmen, Laura, Urbain, and Azucena.[5][10] Cisneros spelled her stage name "Eleonora" instead of "Eleanora".[7]

Cisneros is credited for more marketing promotion of Liberty bonds during World War I than any other person - $30,000,000 worth.[14] She participated free of charge in "an all star cast" of the renown war play Out There as it toured major cities throughout the United States raising funds in World War I for the Red Cross.[15]

Works

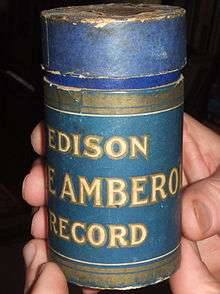

Cisneros recorded various opera songs under the labels of Edison's Blue Amberol Records, Gramophone and Typewriter, Pathé Records, and American Columbia.[13]

One such song is Thomas Dunn English's poem Ben Bolt, recorded on an Edison Blue Amberol cylinder in 1912.[16]

Oh, don't you remember, Sweet Alice, Ben Bolt?

Sweet Alice, whose hair was so brown,

Who wept with delight when you gave her a smile,

And trembled with fear at your frown!

In the old churchyard, in the valley, Ben Bolt,

In a corner obscure and alone,

They have fitted a slab of the granite so gray.

And sweet Alice lies under the stone!

Under the hickory tree, Ben Bolt,

Which stood at the foot of the hill,

Together we've lain in the noon-day shade,

And listened to Appleton's mill.

The mill-wheel has fallen to pieces, Ben Bolt,

The rafters have tumbled in,

And a quiet that crawls round the walls as you gaze,

Has followed the olden din.

Do you mind the cabin of logs, Ben Bolt,

At the edge of the pathless wood,

And the button-ball tree with its motley limbs,

Which nigh by the door-step stood?

The cabin to ruin has gone, Ben Bolt,

The tree you would seek in vain;

And where once the lords of the forest waved,

Grows grass and the golden grain.

And don't you remember the school, Ben Bolt,

With the master so cruel and grim,

And the shaded nook in the running brook,

Where the children went to swim?

Grass grows on the master's grave, Ben Bolt,

The spring of the brook is dry,

And of all the boys who were schoolmates then,

There are only you and I.

There is change in the things I loved, Ben Bolt,

They have changed from the old to the new;

But I feel in the depths of my spirit the truth,

There never was change in you.

Twelve-months twenty have past, Ben Bolt,

Since first we were friends—yet I hail

Thy presence a blessing, thy friendship a truth,

Ben Bolt, of the salt-sea gale![17][18]

Footnotes

- Kutsch & Riemens 1969, p. 82.

- Read & Witlieb 1992, p. 116.

- Commire 1999, p. 771.

- James & Boyer 1971, p. 450.

- "Eleonora de Cisneros". Oxford University Press. 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- Commire 2007, p. 391.

- James & Boyer 1971, p. 451.

- Lahee 1912, p. 146.

- Lahee 1912, p. 147.

- Macy 2008, p. 89.

- Read & Witlieb 1992, p. 117.

- Saerchinger 1918, p. 118.

- Kutsch & Riemens 1969, p. 83.

- James & Boyer 1971, p. 451 "She is also said to have sold $30,000,000 worth of Liberty bonds, the largest amount credited to any individual.".

- Carson 1919, p. 25.

- Edison Blue Amberol cylinder recording of Ben Bolt (1912) on YouTube

- Kish, Kathy (July 28, 2006). "More history comes to light about 'Ben Bolt,' its author". Bluefield Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on February 12, 2014. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- Cheney 1904, pp. 222, 223, 224.

Bibliography

- Carson, Lionel (1919). The Stage Year Book. Stage Offices.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cheney, John Vance (1904). The World's Best Poetry . J.D. Morris.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Commire, Anne (1999). Women in World History. Gale. ISBN 0-7876-4062-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Commire, Anne (2007). Dictionary of Women Worldwide. Gale. ISBN 0-7876-7676-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, Edward & Janet; Boyer, Paul S. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62734-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kutsch, K. J.; Riemens, Leo (1969). A concise biographical dictionary of singers: from the beginning of recorded sound to the present. Chilton Book Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lahee, Henry Charles (1912). The grand opera singers of today: an account of the leading operatic stars who have sung during recent years, together with a sketch of the chief operatic enterprises. L.C. Page and Company. p. 146.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Macy, Laura Williams (2008). The Grove Book of Opera Singers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533765-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Read, Phyllis J.; Witlieb, Bernard L. (1992). The Book of Women's Firsts: Breakthrough Achievements of Almost 1,000 American Women. Random House Information Group. ISBN 978-0-679-40975-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saerchinger, César (1918). International Who's who in Music and Musical Gazetteer. Current Literature Publishing Co. p. 60.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eleonora de Cisneros. |

- Eleonora de Cisneros Home Sweet Home Edison Blue Amberol cylinder on YouTube

- Eleonora de Cisneros - Home Sweet Home 1913 at Internet Archive

- Eleonora de Cisneros -"Oh! Don't you remember sweet Alice!" lyrics on YouTube

- Eleonora de Cisneros Oh! Don't you remember at Internet Archive

- Eleonora de Cisneros 1924 recording of All'udir del sistro il suon

- Eleonora de Cisneros 1913 recording of opera Ah, quel giorno on YouTube

- Eleonora de Cisneros 1912 "Ben Bolt" recording from UCSB

- Eleonora de Cisneros at Find a Grave