Eighth Army Ranger Company

The Eighth Army Ranger Company, also known as the 8213th Army Unit, was a Ranger light infantry company of the United States Army that was active during the Korean War. As a small special forces unit, it specialized in irregular warfare. Intended to combat the North Korean (NK) commandos who had been effective at infiltration and disruption behind United Nations (UN) lines, the Eighth Army Ranger Company was formed at the height of the Battle of Pusan Perimeter in September 1950 and was the first U.S. Army Ranger unit created since World War II. The company went into action as a part of the 25th Infantry Division during the UN advance into North Korea in October and November. It was best known for its defense of Hill 205 against an overwhelming Chinese attack during the Battle of the Ch'ongch'on River which resulted 41 of the 51 Rangers becoming casualties.

| Eighth Army Ranger Company | |

|---|---|

Eighth United States Army shoulder sleeve insignia, which the Eighth Army Ranger Company wore as its own insignia | |

| Active | 24 August 1950 – 28 March 1951 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | United States Army |

| Branch | Active duty |

| Type | Ranger light infantry |

| Role | Irregular warfare |

| Size | Company |

| Part of | Eighth United States Army |

| Garrison/HQ | Pusan, South Korea |

| Engagements | Korean War |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Ralph Puckett John P. Vann Charles G. Ross |

The company later undertook a number of other combat missions during late 1950 and early 1951, conducting infiltration, reconnaissance and raiding. It scouted Chinese positions during Operation Killer and struck behind Chinese lines during Operation Ripper before being deactivated at the end of March 1951. The company saw 164 days of continuous combat and was awarded a Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation. Military historians have since studied the economy of force of the company's organization and utilization. Although the experimental unit led to the creation of 15 more Ranger companies, historians disagree on whether the unit was employed properly as a special forces unit and whether it was adequately equipped for the missions it was designed to conduct.

Origins

—Puckett, speaking later of his experience training the Rangers.[1]

Following the outbreak of the Korean War on 25 June 1950, the North Korean People's Army had invaded the Republic of Korea (ROK) with 90,000 well-trained and equipped troops who had easily overrun the smaller and more poorly equipped Republic of Korea Army.[2] The United States (U.S.) and United Nations (UN) subsequently intervened, beginning a campaign to prevent South Korea from collapsing. The U.S. troops engaged the North Koreans first at the Battle of Osan, and were badly defeated by the better-trained North Koreans on 5 July.[3] By August, U.S. and UN forces had been pushed back to the Pusan Perimeter.[4] At the same time, North Korean agents began to infiltrate behind UN lines and attack military targets and cities.[5] UN units, spread out along the Pusan Perimeter, were having a difficult time repelling these units as they were untrained in combating guerrilla warfare. North Korean special forces units like the NK 766th Independent Infantry Regiment had been successful in defeating ROK troops,[6][7] prompting Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins to order the creation of an elite force which could "infiltrate through enemy lines and attack command posts, artillery, tank parks, and key communications centers or facilities."[8] All U.S. Army Ranger units had been disbanded after World War II because they required time-consuming training, specialization, and expensive equipment.[9] Yet with the defeat of the NK 766th Regiment at the Battle of P'ohang-dong, and the strength of U.S. infantry units in question, U.S. commanders felt recreating Ranger units was essential to beginning a counteroffensive.[10]

In early August as the Battle of Pusan Perimeter was beginning,[8] the Eighth United States Army ordered Lieutenant Colonel John H. McGee, the head of its G-3 Operations Miscellaneous Division, to seek volunteers for a new experimental Army Ranger unit.[5] McGee was given only seven weeks to organize and train the unit before it was sent into combat, as commanders felt the need for Rangers was dire, and that existing soldiers could be trained as Rangers in a relatively short period of time.[9] Because of this limitation, volunteers were solicited only from existing Eighth Army combat units in Korea, though subsequent Ranger companies were able to recruit Ranger veterans from World War II.[8] From the Eighth Army replacement pool,[11] McGee recruited Second Lieutenant Ralph Puckett, newly commissioned from West Point and with no combat experience, to serve as the company commander.[9] Second Lieutenants Charles Bunn and Barnard Cummings, Jr., became Puckett's two platoon leaders.[12] Several hundred enlisted men volunteered from the Eighth Army, though few had combat experience. Through a quick and informal selection process, Puckett picked the men to fill out the company based on weapons qualifications, athleticism, and duty performance. There was no time to administer physical fitness tests for the applicants, and unmarried men younger than 26 were preferred. Recruits were told they would receive no hazard pay.[6]

Once Puckett had selected 73 enlisted men,[6][n 1] the Eighth Army Ranger Company was formally organized at Camp Drake, Japan, on 25 August 1950.[8] Three days later, it sailed from Sasebo to Pusan, South Korea, aboard the ferry Koan Maru. Upon arrival, the company was sent to the newly established Eighth Army Ranger Training Center for seven weeks of specialized training. This took place at "Ranger Hill"[6][11] near Kijang,[12] where the men became skilled in reconnaissance, navigation, long-range patrolling, motorized scouting, setting up roadblocks, maintaining camouflage and concealment, and adjusting indirect fire. They also undertook frequent live fire exercises, many at night, simulating raids, ambushes and infiltration, using North Korean operatives that were known to be hiding in the area as an opposing force.[6] Adopting techniques that had been established during World War II, they worked 60 hours per week, running 5 miles (8.0 km) each day and frequently undertaking 20-mile (32 km) speed marches.[13] The troops also all shaved their hair into mohawks, under orders of the officers who wanted to build esprit de corps.[11] Of the original 76 men who started the course, 12 either dropped out or were injured,[14] and as a result 10 South Korean troops, known as KATUSAs, were attached to the unit to fill its ranks.[15][n 2]

Organization

Established to experiment with the notion of deploying small light infantry units that specialized in infiltration and irregular warfare to Korea, the Eighth Army Ranger Company was created with an organization that was unique to other U.S. Army units. Consisting of three officers and 73 enlisted men,[8][n 3] it was organized as a company of two platoons based on the Table of Organization and Equipment documents used to raise Ranger units during World War II.[9] Within each platoon, a headquarters element of five men (a platoon leader, platoon sergeant, platoon guide, and 2 messengers) provided command and control. In addition, both platoons had thirty-six men in three squads – two assault squads and one heavy weapons squad – and were furnished with a 60 mm M2 mortar, two M20 Super Bazookas, and a M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle as well as the M1 Garand and M2 Carbines that the majority of the men were armed with. One man from each platoon was designated as a sniper. The company was assigned no vehicles,[6] and no provision was made for mess facilities or to provide medical assets. As no independent battalion-level headquarters existed in Korea, the company had to be attached to a higher formation at all times.[16]

Employing the Sub Intelligent Numbers Selector theory that assigned non-descript unit names and randomized numerical designations to formations in order to disguise their role from the enemy, the company was designated the 8213th Army Unit. Upon formation, it was decided that the company would be considered an ad hoc, or provisional unit, which meant it did not have a permanent lineage and was only a temporary formation, akin to a task force.[6] This decision was unique to the Eighth Army Ranger Company, as subsequent companies assumed the lineage of Ranger units from World War II, and veterans later expressed resentment with the choice as it prevented the company from accruing its own campaign streamers or unit decorations.[17] While subsequent Ranger companies were authorized shoulder sleeve insignia with the distinctive black and red scroll of their World War II predecessors, the Eighth Army Ranger Company wore the shoulder patch of the Eighth United States Army, which commanded all UN troops in Korea.[18]

History

Advance

By the time the Eighth Army Ranger Company completed training on 1 October, UN forces had broken out of the Pusan Perimeter following an amphibious landing at Inchon.[19] The company was subsequently committed to the offensive from Pusan Perimeter. On 8 October it was redesignated the 8213th Army Unit signifying its activation as a unit, and on 14 October Puckett took an advance force to join the US 25th Infantry Division at Taejon, as part of the US IX Corps.[15] The Rangers' first assignment was to probe north to Poun with the division's reconnaissance elements in search of pockets of guerrillas which had been isolated during the UN breakout from Pusan.[14] The platoons moved to two villages near Poun and began a northward sweep with the 25th Infantry Division. The troops then rapidly moved 175 miles (282 km) to Kaesong where they eliminated the last North Korean resistance south of the 38th Parallel.[20] In these missions, the Eighth Army Ranger Company saw frequent combat with small groups of North Korean troops.[15] During this time they also scrounged supplies from local units, including commandeering a jeep, and taking rice and other rations from the countryside.[14]

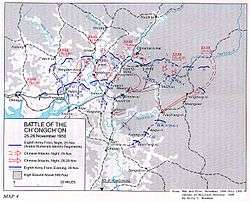

With South Korea liberated, the Rangers led the 25th Infantry Division's advance into North Korea. Acting as a spearhead, they sent out reconnaissance patrols ahead of the divisional main body and set up roadblocks to limit the movement of retreating North Korean forces. The Rangers became a part of "Task Force Johnson" with the 25th Infantry Division Reconnaissance Company and the 2nd Battalion, 35th Infantry in November to probe and clear the Uijeongbu, Dongducheon, and Shiny-ri areas of North Korean elements. On 18 November, the Rangers were detached from Task Force Johnson and returned to Kaesong, where they were attached to the 89th Medium Tank Battalion. On 20 November, the 89th Medium Tank Battalion moved to join the renewed UN offensive north to destroy the remaining North Korean troops and advance to the Yalu River. The battalion was designated "Task Force Dolvin" and ordered to spearhead the drive. At 01:00 that morning they advanced to Kunu-ri, reaching the front lines at Yongdungpo by 16:00.[15]

Hill 205

On 23 November, the 25th Infantry Division rested in preparation for its final advance to the Yalu, which was to begin the next day at 10:00. As the division spent the day enjoying a Thanksgiving Day meal, the Rangers scouted 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) north of the planned line of departure but made no contact with North Korean forces. On 24 November, the company moved out on time in the center of Task Force Dolvin's advance, riding on tanks from B Company, 89th Tank Battalion,[21] including M4A3 Sherman and M26 Pershings.[22] About 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) into their advance, they rescued 30 U.S. prisoners of war from the 8th Cavalry Regiment who had been captured at the Battle of Unsan but abandoned by the retreating Chinese. At 14:00 they reached their objective at Hill 222. As soon as the Rangers dismounted the tanks, the troops came under mortar fire.[21] One Ranger was subsequently killed, the company's first fatality since its formation.[14] Cummings and 2nd Platoon advanced 800 meters (2,600 ft) to the crest of the hill. At that time the tanks of the 89th mistakenly opened fire on the Rangers, causing a number of friendly fire casualties including two killed, before Puckett was able to signal them to stop.[14][21] The Rangers took up positions on Hill 222 for the night.[21] An additional two men became weather casualties, suffering frostbite that evening as temperatures fell to 0 °F (−18 °C).[14]

The next day, 25 November, Task Force Dolvin resumed its advance, with 51 Rangers of the Eighth Army Ranger Company continuing north on the 89th's tanks. The troops immediately ran into Chinese resistance as they began to advance. On both flanks, Task Force Dolvin troops encountered sporadic resistance throughout the morning, but were able to capture their objectives. The Eighth Army Ranger Company rode the tanks a further 5 kilometers (3.1 mi) north to Hill 205. As the Rangers and tanks approached the hill they came under mortar and small arms fire,[23] but were able to capture the hill after light Chinese resistance,[21] suffering four[n 4] wounded in the process.[24] The Rangers then established a perimeter on the position and spent the remainder of the day fortifying it.[25] The Chinese Second Phase Offensive was launched that evening, with the unprepared UN troops hit all along the Korean front as 300,000 Chinese troops swarmed into Korea.[14][26] Several kilometers away on the Rangers' left flank, the U.S. 27th Infantry Regiment's E Company was hit with a heavy Chinese attack at 21:00, alerting the Rangers to a pending attack.[25]

At 22:00, troops of the Chinese 39th Army began a frontal assault on Hill 205, signaled by drums and whistles.[25] An estimated platoon-sized force of Chinese made the first attack.[14] The Rangers fought back with heavy small arms fire and several pre-sighted artillery concentrations, repulsing this first attack at 22:50. A number of Rangers were wounded in this attack, including Puckett, who refused evacuation. At 23:00 the Chinese launched a second attack which was quickly repelled, as was a third attack several minutes later.[25] Both of these attacks were an estimated company in strength.[14] The Rangers inflicted heavy casualties each time as a result of a well-established defensive perimeter, though the platoon of tanks at the foot of the hill opposite the Chinese attack were unable to assist the Rangers, as the crews had no experience in night operations.[27] By 23:50 the Chinese began attacking in greater numbers, with an estimated two companies advancing at a time,[14] moving to within hand grenade range. The Rangers began to run low on ammunition while their casualties continued to mount, and Puckett was wounded again. Over the course of several hours the Chinese launched a fourth and a fifth attack, each of which was narrowly pushed back by the Rangers. The Rangers were then ordered to fix bayonets in preparation for the next attack.[25]

—Puckett's final radio transmission from Hill 205.[25]

At 02:45, the Chinese began a sixth and final attack with a heavy mortar barrage which inflicted heavy casualties on the remaining Rangers,[25] including Cummings, who was killed instantly by a mortar shell[16] and Puckett, who was severely wounded.[28] The Chinese then sent a reinforced battalion of 600 infantry at the hill,[27] while simultaneously striking other elements of Task Force Dolvin, preventing artillery from providing effective support.[14][n 5] Without artillery support of their own, and low on ammunition, they were overwhelmed by the subsequent Chinese attack.[27] The Chinese forces swarmed the hill in overwhelming numbers, and many of the Rangers were shot and killed in their foxholes or stabbed with bayonets. The company was destroyed in the fighting, with the survivors retreating from the hill. Three Rangers later chased away Chinese troops as they tried to capture the severely wounded Puckett.[n 6] The remaining Rangers gathered at an assembly area at the base of the hill[25] under First Sergeant Charles L. Pitts, the highest ranking unwounded member of the company, and withdrew. The Rangers suffered over 80 percent casualties on Hill 205; of the 51 who captured the hill, 10 were killed or missing and another 31 wounded.[24]

1951 raids

The heavy casualties on Hill 205 rendered the company ineffective,[29] and for several weeks it was only capable of being used to conduct routine patrols or as a security force for divisional headquarters elements. Puckett was evacuated to recover from his wounds.[24] On 5 December, Captain John P. Vann assumed command of the company, and Captain Bob Sigholtz, a veteran of Merrill's Marauders, was also assigned to the unit.[30] Yet with the company's casualties being replaced by regular soldiers who had no Ranger training it did not return to full combat capability after the Hill 205 battle. The replacements were subsequently given cursory training between missions, but U.S. military historians contend that the inexperienced replacements dramatically decreased the usefulness of the company as a special forces unit. The company participated in a few isolated missions in late 1950 and early 1951, including the recapture of Ganghwa Island from Chinese forces while attached to the Turkish Brigade. It advanced with the 25th Division during Operation Killer in late February as part of an effort to push Chinese forces north of the Han River.[24] During that operation the company was employed as a scouting force, probing the strength of Chinese formations as they launched raids and attacks on the 25th Infantry Division. The frequent scouting missions were also intended to draw Chinese fire and determine the locations of their units.[31]

Returning to action, the company's 2nd Platoon effected a crossing of the Han River at 22:00 on 28 February 1951 for a raid on Yangsu-ri to destroy Chinese positions and capture a prisoner. Despite difficulties crossing the icy river the platoon moved into the village after 23:00, finding it deserted. After probing 1 mile (1.6 km) north and finding no Chinese, the Rangers returned to UN lines. On 1 March, 1st Platoon conducted a follow-up mission to scout railroad tunnels north of the village but had to turn back as heavy ice blocked its boats from crossing, and several men fell into the freezing water.[32] During the first days of March, the company stepped up its patrols across the Han River, this time with a renewed emphasis on determining the locations of Chinese forces and pinpointing their strongpoints, in preparation for the next major offensive.[33]

Operation Ripper

Vann was replaced by Captain Charles G. Ross[34] on 5 March 1951.[24] At the same time, the UN began Operation Ripper to drive the Chinese north of the 38th Parallel. As the 25th Infantry Division attacked forward, the Eighth Army Ranger Company scouted 6 miles (9.7 km) ahead of the general attack, reconnoitering Chinese positions. For much of the month they were utilized as a flank security force for the 25th Infantry Division, holding successive blocking positions as elements of the division advanced. On 18 March, they were sent a further 7 miles (11 km) north of the front lines to set up an ambush at a road and railway line which ran through a defile. Chinese troops were retreating through this defile, and at 15:30 on 19 March Ross assembled the men nearby. Through the night they established roadblocks and prepared to attack oncoming Chinese troops, but none passed through the area, and Ross took the company back to UN lines at 05:00.[32]

The company's final mission came on 27 March, an infiltration 6 miles (9.7 km) north to Changgo-ri to reconnoiter the size of a Chinese force holding there and to prevent it from setting a rearguard. The 25th Infantry Division would then attack and overwhelm the Chinese concentration more easily. The Rangers began their advance at 22:00 and arrived at the village at 01:00. Ross then ordered 2nd Platoon to conduct a stealth attack into the village which destroyed an outpost and a food cache and caught the Chinese troops by surprise. The Rangers temporarily succeeded in pushing the sizable Chinese force out of the village and into a trench, inflicting heavy casualties on it in the process. The Chinese, estimated to be a battalion, subsequently attempted to counterattack but were repulsed by the Rangers. Following this, Ross ordered the company to withdraw back to UN lines, arriving there at 05:00 having suffered no casualties in the action.[32]

The Eighth Army Ranger Company was deactivated on 31 March 1951.[24] Some of its equipment was subsequently consolidated with the 5th Ranger Infantry Company, which was newly arrived in Korea and had been assigned to the 25th Infantry Division.[34] The men of the new Ranger company had formally attended Ranger School, though they were inexperienced and less effective in their initial actions with the division.[35] In the meantime, most of the men of the former Eighth Army Ranger Company were transferred to other units of the 25th Infantry Division, while those who were paratrooper qualified through the United States Army Airborne School were allowed to transfer to the 187th Regimental Combat Team or one of the other Ranger companies then beginning to arrive in Korea.[32] During its brief existence, the Eighth Army Ranger Company saw 164 days of combat and was awarded a Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation.[24]

Analysis

In September 1950, on Collins' orders the Ranger Training Center was moved to Fort Benning, Georgia, and in October the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Ranger Companies began training.[36] The effective employment of the Eighth Army Ranger Company had demonstrated the viability of the concept to Army planners, and the subsequent Chinese attacks in November reinforced the need for more such units. As a result, the 5th, 6th, 7th, and 8th Ranger Companies were ordered to form. Altogether, another fifteen Ranger companies would be formed in 1950 and 1951, and six of them would see combat in Korea.[37]

Subsequent military science studies of the use of Rangers during the Korean War have focused on analysing their economy of force by looking at how well the U.S. military employed them as special forces. In an analysis of the operations of all Ranger units in the Korean War, Major Chelsea Y. Chae proposed in a 1996 thesis to the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College that they were misused and ineffective in general, and that in particular the Eighth Army Ranger Company had been poorly employed.[38] Chae noted that the Ranger formations' lack of support personnel made them a logistic and administrative liability, as they had to be attached to conventional units for support.[39] Furthermore, he argued that the Rangers' small formation sizes[n 1] meant that they lacked the manpower to conduct basic tactical maneuvers,[40] and their employment with divisional elements did not provide them with the intelligence information necessary for effective infiltration operations.[41] He concluded that these problems were due to a "lack of understanding of Ranger capabilities, limitations inherent in Rangers–——°' force structure, and basic distrust of elite forces."[38]

However, retired Colonel Thomas H. Taylor, a military historian, contended in his 1996 book that in spite of their original purpose of short range infiltration, the Eighth Army Ranger Company was employed well for the missions they conducted, most of which were reactionary and borne out of a need to rapidly counter North Korean and Chinese attacks. Taylor noted that particularly in their earlier missions, the Rangers had been successful at operating as a night combat force, a skill that the rest of the U.S. forces in Korea were largely untrained in. Taylor also believed that the Rangers, who were drawn from replacement and occupation units in Japan, effectively gave the 25th Infantry Division an extra force it would not otherwise have possessed, allowing it to employ its conventional forces elsewhere. Taylor praised division commander Major General William B. Kean for his employment of the Rangers,[32] and argued that the successes of the subsequent Ranger companies validated the existence of the Eighth Army Ranger Company.[36]

References

Notes

- Subsequent Ranger companies were allowed a strength of between 112 and 122 men, as compared to the standard infantry company strength of 211. (Veritas Part 2 2010, p. 3)

- The KATUSAs were attached to the unit and employed as translators and guides only, and were not technically qualified as Rangers. (Taylor 1996, p. 99)

- Later, the establishment of Ranger companies was increased and they were organized in three platoons, and equipped with additional heavy weapons. (Black 2002, p. 2 (Ch. 4))

- Taylor 1996, p. 99 states that six Rangers and three KATUSAs were wounded, but other sources do not corroborate this claim.

- Although US histories generally agree that the Chinese 39th Army launched a major offensive against Task Force Dolvin on the night of 25 November, Commander Wu Xinquan of the 39th Army could not recall whether any attack orders were issued on 25 November. However, Wu did state that during the strategy meeting that took place that night, the Chinese 345th Regiment reported that one of its infantry battalions had been badly mauled by Task Force Dolvin. (Wu & Wang 1996, pp. 125–126)

- Two of the Rangers who rescued Puckett, Private First Class Billy G. Walls and Sergeant David L. Pollock, were awarded the Silver Star Medal for their actions. (Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 42)

Citations

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 37

- Varhola 2000, p. 2

- Varhola 2000, p. 3

- Varhola 2000, p. 4

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 35

- Taylor 1996, p. 98

- Veritas Part 2 2010, p. 2

- Dilley & Zedric 1999, p. 201

- Sizer 2009, p. 234

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 34

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 36

- Sizer 2009, p. 235

- Dilley & Zedric 1999, p. 202

- Taylor 1996, p. 99

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 38

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 44

- Black 2002, p. 1 (Ch. 4)

- Black 2002, p. 1 (Appendix B)

- Sizer 2009, p. 236

- Sizer 2009, p. 238

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 41

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 40

- Sizer 2009, p. 240

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 43

- Veritas Part 1 2010, p. 42

- Keliher & Sincock 2002, p. 62

- Sizer 2009, p. 241

- Sizer 2009, p. 242

- Taylor 1996, p. 100

- Hagerman 1990, p. 430

- Keliher & Sincock 2002, p. 73

- Taylor 1996, p. 102

- Keliher & Sincock 2002, p. 74

- Hagerman 1990, p. 432

- Keliher & Sincock 2002, p. 92

- Taylor 1996, p. 103

- Taylor 1996, p. 104

- Chae 1996, p. 7

- Chae 1996, p. 51

- Chae 1996, p. 53

- Chae 1996, p. 54

Sources

- "ARSOF in the Korean War, Part I" (PDF), Veritas: Journal of Army Special Operations History, Fort Bragg, North Carolina: United States Army Special Operations Command, 6 (1), 2010, ISSN 1553-9830, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2012

- "ARSOF in the Korean War, Part II" (PDF), Veritas: Journal of Army Special Operations History, Fort Bragg, North Carolina: United States Army Special Operations Command, 6 (2), 2010, ISSN 1553-9830, archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2012

- Black, Robert W. (2002), Rangers in Korea, New York City: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-8041-0213-1

- Chae, Chelsea Y. (1996), The Roles and Missions for Rangers in the Twenty-First Century (PDF), Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College

- Dilley, Michael F.; Zedric, Lance Q. (1999), Elite Warriors: 300 Years of America's Best Fighting Troops, Ventura, California: Pathfinder Publishing of California, ISBN 978-0-934793-60-5

- Hagerman, Bart (1990), USA Airborne: 50th Anniversary, Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-938021-90-2

- Keliher, John; Sincock, Morgan (2002), Twenty-Fifth Infantry Division: Tropic Lightning, Korea, 1950–1954, Volume 2, Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 1-56311-826-2

- Sizer, Mona D. (2009), The Glory Guys: The Story of the U.S. Army Rangers, Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publishing, ISBN 978-1-58979-392-7

- Taylor, Thomas (1996), Rangers Lead the Way, Nashville, Tennessee: Turner Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-56311-182-2

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000), Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953, Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press, ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4

- Wu, Xin Quan (吳信泉); Wang, Zhao Yun (王照运) (1996), 1000 Days on the Korean Battlefield: 39th Corps in Korea (朝鲜战场1000天 : 三十九军在朝鲜) (in Chinese), Shenyang, China: Liaoning People's Publishing House, ISBN 7-205-03504-X