Egmond Gospels

The Egmond Gospels (Dutch: Evangeliarium van Egmond) is a 9th-century Gospel Book written in Latin and accompanied by illustrations. It is named after the Egmond Abbey, to which it was given by Dirk II, and where it remained for six centuries. It is most famous for being the earliest surviving manuscript showing scenes with Dutch people and buildings, and represents one of the oldest surviving Christian art treasures from the Netherlands. The manuscript has been owned by the Royal Library of the Netherlands since 1830.

Codicological information

The manuscript consists of 218 vellum folios measuring 232 by 207 mm. Its Latin text is written in a single column of Carolingian minuscule of 20 lines measuring 156 by 126 mm. Its original binding was made of oak boards covered in gold and set with gemstones, which is described in the "Rijmkroniek van Holland" (Rhyming Chronicle of Holland) that was written around 1300. In another description from 1805, Hendrik van Wijn describes a binding of wooden boards covered in brown leather, unmarked except for the date 1574. This is likely the year when the valuable binding was removed. The binding was replaced again in 1830 when it was acquired by the Royal Library of the Netherlands, and once more in 1949 with a calfskin parchment after it appeared that the previous hard-glued spine caused damage. Its current binding is made of white goat's skin and dates to a restoration in 1995.

History

The manuscript was written in the third quarter of the 9th century in northwestern France, likely in Reims.[1] It is not known who commissioned it.

Around 900, eight folios were added to the manuscript, two at the beginning of each gospel. On the verso side of the first folio is the evangelist's symbol, and on the recto side on the second is his portrait. The second folio's verso side displays the incipit. The text on the following page was adjusted to reproduce the first letters of the text in large, decorative letters. It is still possible to see places where the original text was taken out, for example folio 19 recto, at the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew in the Liber Generationis. A space above the first line 'XPI FILII DAVID FILII ABRAHAM' is clearly visible, where the text has been removed and brought to the preceding pages. The page likely originally began: ‘INC EVANG SCDM MATTHEUM / LIBER GENERATIONIS / IHU XPI FILII DAVID FILII ABRAHAM'. The removed text was rewritten in decorative letters on the added folios 17v, 18r, and 19v. At this time the manuscript's current canon tables were also added. These seven folios precede the Gospel of Matthew and may have replaced the original canon tables, or have been the first ones themselves.

The manuscript later came into the hands of the Frisian count Dirk II, who had its binding richly gilded and decorated with gemstones. He also added two miniatures paintings, in a diptych, in the back of the manuscript. These depict him and his consort, Hildegard of Flanders, giving the manuscript to the Egmond Abbey. The miniature paintings were likely added in Ghent between 975-988, while the gift itself took place in 975.[1][2][3]

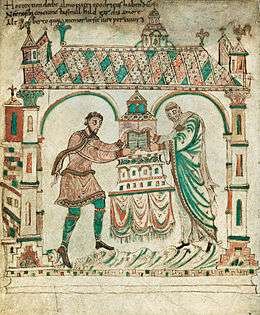

The left miniature on folio 214 verso shows Dirk and Hildegard underneath an arched structure with the open gospel book lying on an altar. The exterior of the abbey (certainly a fictional representation) is depicted as an architectural frame for the event. The text in the upper lefthand corner indicates what is happening:

- Hoc textum dedit almo patri Teodricus habendum

- Necne sibi coniuncta simul Hildgardis amore

- Altberto quorum memor ut sit iure per evum

(This book was given by Dirk and his wife Hildegard to the merciful father Adalbert, so that he will think of them in eternity.)

The recto side shows Dirk kneeling and Hildegard lying in proskynesis before Adalbert, the patron saint of the abbey, who pleads on their behalf to a Christ in Majesty. The accompany text reads:

- Summe Deus rogito miserans conserva benigne, hos tibi quo iugitur formulari digne laborent

The circular space around Christ likely suggests a Byzantian dome.

The manuscript was kept at the Egmond Abbey until the Dutch Revolt. It was recorded in the abbey's inventory in 1571. In 1573, the abbey was looted and destroyed, but the Egmond Gospels had already been transported to safety in Haarlem by Godfried van Mierlo, the abbot of Egmond and bishop of Haarlem.[4][5]:177 The manuscript was handed over in 1578 to Pieter van Driel, the tax collector of Haarlem, along with a number of other valuable items. In 1583, Van Mierlo transferred its possession to Hendrik Bercheyk, from the Dominican monastery in Cologne.[5]:177

The Egmond Gospels remained in Cologne with the Dominicans until 1604. In that year Van Mierlo's successor, Sasbout Vosmeer took it into his possession after he was made apostolic vicariate of the diocese of Haarlem.[5]:177 The manuscript was likely kept at the seminary Vosmeer founded in Cologne.

The manuscript returned to the Netherlands between 1656 and 1688, namely to Utrecht. In 1688, it was in the possession of the Geertekerk according to a note written by Joannes Lindeborne. Lindeborn was the pastor at St. Nicolaas and had been a student and rector at Vosmeer's seminary in Cologne.[5]:172 It is likely that Lindeborn brought the manuscript to Utrecht after the seminary was closed in 1683.

In 1802, the Utrecht council member and archivist Petrus van Musschenbroek rediscovered the manuscript in the possession of Timot de Jongh, the pastor of the Old Roman church in Utrecht's Hoek.[5]:177 Van Musschenbroek's colleague, Hendrik van Wijn, had described the manuscript in his 1805 book "Huiszittend Leven" ("Domestic Life"). The manuscript had also been identified in 1720 by a previous pastor of the Old Roman church, Willibrord Kemp.[5]:177

In 1830, King William I purchased the Egmond Gospels for 800 guilders and donated it to the Royal Library.

References

- Beschrijving Meermanno Archived 2013-07-03 at Archive.today

- Koninklijke Bibliotheek

- Elisabeth Moore, 'Evangeliarium van Egmond', in: Patrick de Rynck (red.), Meesterlijke middeleeuwen: Miniaturen van Karel de Grote tot Karel de Stoute, 800-1475, Zwolle en Leuven 2002, p.123.

- Hendrik van Wijn, Huiszittend leven, Vol II, Amsterdam, 1817, p.340.

- J.H. Hofman, Iets Nieuws met wat Ouds, over Egmonds Graaflijk Evangelieboek in: Dietsche Warande. Nieuwe reeks. Deel 2. C.L. van Langenhuysen, Amsterdam 1879

Sources and external links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Egmond Gospels. |