Edward W. Pearson Sr.

Edward Walton Pearson, Sr. (January 25, 1872–July 4, 1946)[1] was an African American entrepreneur,[2] Buffalo Soldier and Spanish–American War veteran, civil rights leader, and pioneering sports enthusiast. He moved to Asheville, North Carolina in 1906 and became known as the "Black Mayor of West Asheville" because of his influence in African American neighborhood development and community life.[3]

Edward Walton Pearson, Sr. | |

|---|---|

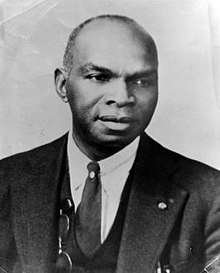

1937 portrait of Edward W. Pearson, Sr. | |

| Born | January 25, 1872 Glen Alpine, Burke County, North Carolina |

| Died | July 4, 1946 |

| Spouse(s) | Annis Bradshaw Pearson |

| Children | Iola Pearson Byers, Annette Pearson Cotton, and Edward W. Pearson, Jr. |

| Parent(s) | Sindy and Edward Pearson |

Early life and education

Pearson was born in Glen Alpine, North Carolina, in Burke County. He completed school through the fourth grade.

Interested in mining, he moved to Jellico, Tennessee, where he enlisted in the Army. He served as a Buffalo Soldier (9th Cavalry Troop B) from 1893-1898 in Fort Robinson, Nebraska during the Spanish-American War.

After being discharged from the Army, he lived in Chicago, where he supplemented his early formal education by taking correspondence courses on insurance, business, religion, and law,[4] including courses at the Chicago Correspondence School of Law.[5]

Business ventures

Pearson began development of Asheville's Burton Street (then known as Pearson Park)[6] and Park View neighborhoods[7] as African American subdivisions. These neighborhoods have continued to be predominantly African American. He also sold real estate for development in this area as an agent on behalf of developer and librarian Rutherford Platt Hayes, son of President Rutherford B. Hayes.[7]

In addition to his real estate ventures, Pearson operated a general store, organized the Mountain City Mutual Insurance Company and ran a mail order shoe business called Piedmont Shoe Company.[8] The general store in West Asheville served as the home base for these operations.[4]

Agricultural fair

Pearson's commitment to improving the lives of African Americans in Asheville also extended to recreational activities and community life. Part of his property in the Burton Street neighborhood included Pearson Park, which he donated to the City of Asheville.[4] In 1914, he organized the Buncombe County and District Colored Agricultural Fair there. One of the largest agricultural fairs in the Southeast, it attracted visitors of all races from all over Western North Carolina and South Carolina,[2] and included amusement park rides, games, livestock shows, and cash prize competitions in categories ranging from baked goods to flower arrangement.[8] It was held annually until 1947, a year after Pearson's death,[1] and later revived as the Burton Street Agricultural Fair.

Baseball

In 1916, Pearson formed the Asheville Royal Giants, Asheville's first black semi-professional baseball team. The Royal Giants played at Oates Park on Asheville's south side[9] and sometimes at Pearson Park.[10] Baseball was not a full-time career for his players, many of whom held jobs at Biltmore Estate, on trains, or in hotels like the Grove Park Inn, Battery Park Hotel, and the former George Vanderbilt Hotel.[11]

In 1921, Pearson also founded and became president of the Blue Ridge Colored Baseball League.[12]

Other organizations

Pearson was very involved in community organizations. In 1933, he organized and was first president of the Asheville branch of the NAACP. He also served as president of the Asheville chapters of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the North Carolina Negro Improvement Association.[4]

Additionally, Pearson was a member of several fraternal groups, including the Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythias, and the Freemasons, among whom he held the office of Grand Master.

Family

Pearson and his family lived in a home behind the general store he operated in West Asheville. His wife was Annis Bradshaw Pearson. They had two daughters, Iola Pearson Byers and Annette Pearson Cotton, and one son, Edward W. Pearson Jr.[8]

Legacy

Pearson's legacy has been commemorated in Asheville with a community identification sign in 2008[13] as well as larger-than-life mural painted on the back of Burton Street Community Center in 2014 for the 100th anniversary celebration of the agricultural fair that Pearson first organized in 1914. The fair was revived and renamed the Burton Street Agricultural Fair in 2012.[3]

References

- "Edward W. Pearson Sr – West Asheville History". westashevillehistory.org. Archived from the original on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- "Renaissance Man: Edward W. Pearson". The Urban News. 2014-02-13. Archived from the original on 2018-09-02. Retrieved 2018-09-01.

- Asheville Design Center, Western North Carolina Alliance, and Burton Street Community Association (Summer 2010). "Burton Street Community Plan" (PDF). Asheville Design Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-27. Retrieved 2019-02-28.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- D., Frazier, Kevan. Legendary locals of Asheville, North Carolina / Kevan D. Frazier. Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 1467101672. OCLC 880861826.

- "Burton Street". www.tiki-toki.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- "Burton Street Neighborhood Profile « Announcements « Asheville City Source". Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- "Black History Month: Edward R. Pearson". Citizen Times. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- "A Valentine for E. W. Pearson, Sr". Heard Tell: Stories From the North Carolina Room. 2014-02-07. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- Calder, Thomas. "Asheville Archives: Royal Giants take the field, 1916". Mountain Xpress. Archived from the original on 2019-02-26. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- Neufeld, Rob (2018-07-01). "Visiting Our Past: Untold stories of Asheville's Riverside Park". Asheville Citizen-Times. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- Mueller, Thomas R. (2004-03-05). "Baseball in the Carolinas: 25 Essays on the States' Hardball Heritage (review)". NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture. 12 (2): 161–163. doi:10.1353/nin.2004.0024. ISSN 1534-1844. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- Ballew, Bill (2004). Baseball in Asheville. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 9781439612545. OCLC 630551978.

- Bowe, Rebecca. "Asheville's black history honored on Burton Street". Mountain Xpress. Archived from the original on 2019-03-01. Retrieved 2019-02-28.