Edmund Cartwright

Edmund Cartwright FSA (24 April 1743 – 30 October 1823) was an English inventor.[1] He graduated from Oxford University very early and went on to invent the power loom. Married to local Elizabeth McMac at 19, he was the brother of Major John Cartwright, a political reformer and radical, and George Cartwright, explorer of Labrador.

Edmund Cartwright | |

|---|---|

Edmund Cartwright | |

| Born | 24 April 1743 Marnham, Nottinghamshire, England |

| Died | 30 October 1823 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | Battle, Sussex |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | Oxford University |

| Occupation | Clergyman, inventor |

| Known for | Power loom |

| Signature | |

Early life

Cartwright was taught at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Wakefield, University College, Oxford, and for an MA degree at Magdalen College, Oxford, (awarded 1766) where he was received a demyship and was elected a Fellow of the College.[2] He became a clergyman of the Church of England. Cartwright began his career as a clergyman, becoming, in 1779, rector of Goadby Marwood, Leicestershire. In 1783, he was elected a prebendary at Lincoln Cathedral. During his time as a clergyman he published the poem Armine and Elvira in 1770, which was followed by The Prince of Peace in 1779. Although he became better-known as an inventor he was awarded the degree of DD in 1806.[3]

Power loom

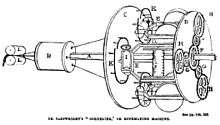

Edmund Cartwright designed his first power loom in 1784 and patented it in 1785, but it proved to be valueless. In 1789, he patented another loom which served as the model for later inventors to work upon. For a mechanically driven loom to become a commercial success, either one person would have to be able to attend to more than one machine, or each machine must have a greater productive capacity than one manually controlled.

Cartwright added improvements, including a positive let-off motion, warp and weft stop motions, and sizing the warp while the loom was in action. He commenced to manufacture fabrics in Doncaster using these looms, and discovered many of their shortcomings. He attempted to remedy these in a number of ways: by introducing a crank and eccentric wheels to actuate its batten differentially, by improving the dicking mechanism, by means of a device for stopping the loom when a shuttle failed to enter a shuttle box, by preventing a shuttle from rebounding when in a box, and by stretching the cloth with temples that acted automatically. His mill was repossessed by creditors in 1793.[3]

In 1792, Cartwright obtained his last patent for weaving machinery; this provided his loom with multiple shuttle boxes for weaving checks and cross stripes.[3] However all his efforts were unavailing; it became apparent that no mechanism, however perfect, could succeed so long as warps continued to be sized while a loom was stationary. His plans for sizing them while a loom was in operation, and before being placed in a loom, failed. These problems were resolved in 1803, by William Radcliffe and his assistant Thomas Johnson, by their inventions of the beam warper, and the dressing sizing machine.

In 1790 Robert Grimshaw of Gorton, Manchester erected a weaving factory at Knott Mill which he intended to fill with 500 of Cartwright's power looms, but with only 30 in place the factory was burnt down, probably as an act of arson inspired by the fears of hand loom weavers. The prospect of success was not sufficiently promising to induce its re-erection.

In 1809 Cartwright obtained a grant of £10,000 from parliament for his invention.[3] In May 1821, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[4]

Other inventions

Cartwright also patented a wool combing machine in 1789 and a cordelier (machine for making rope) in 1792. He also designed a steam engine that used alcohol instead of water.[3]

Family

Following the award of the parliamentary grant, Cartwright purchased a small farm in Kent, where he spent the rest of his life. [3] Edmund Cartwright died in Sussex after a lingering illness[5] and was buried at Battle.[6]

His daughter Elizabeth (1780–1837) married the Reverend John Penrose and wrote books under the pseudonym of Mrs Markham.

References

- "Edmund Cartwright (1743–1823)". History. BBC. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Edmund Cartwright". Lemelson-MIT. MIT. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 435.

- "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- Cave, Edward (1833). "Obituary: Rev. Edmund Cartwright". Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle. Edward Cave: 374.

- Strickland (?), M. (1843). A Memoir of the Life, Writings, and Inventions, of Edmund Cartwright, D.D. FRS, Inventor of is Power Loom, Etc. Etc. London: Saunders and Otley.

Further reading

- Cartwright, Edmund (1772). Armine and Elvira: A Legendary Tale (3 ed.). London: John Murray.

Edmund Cartwright.

- Strickland, Mary (1843). A Memoir of the Life, Writings, and Inventions, of Edmund Cartwright, D.D. FRS, Inventor of the Power Loom, Etc. Etc. London: Saunders and Otley. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- Hunt, David. "Cartwright, Edmund (1743–1823)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4813. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Edmund Cartwright |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edmund Cartwright. |

- "Edmund Cartwright and the power loom" – at Cotton Times

- "Richard Arkwright and Edmund Cartwright: Inventors of Important Textile Manufacturing Machines" – at Grimshaw Origins