Earl of Holderness

The title Earl of Holderness also known as Holdernesse existed in the late 11th and early 12th centuries as a feudal lordship and was officially created three times in the Peerage of England namely in 1621, in 1644 as a subsidiary title to that of the then-Duke of Cumberland and in 1682. The official creations lasted 5, 38 and 96 years respectively.

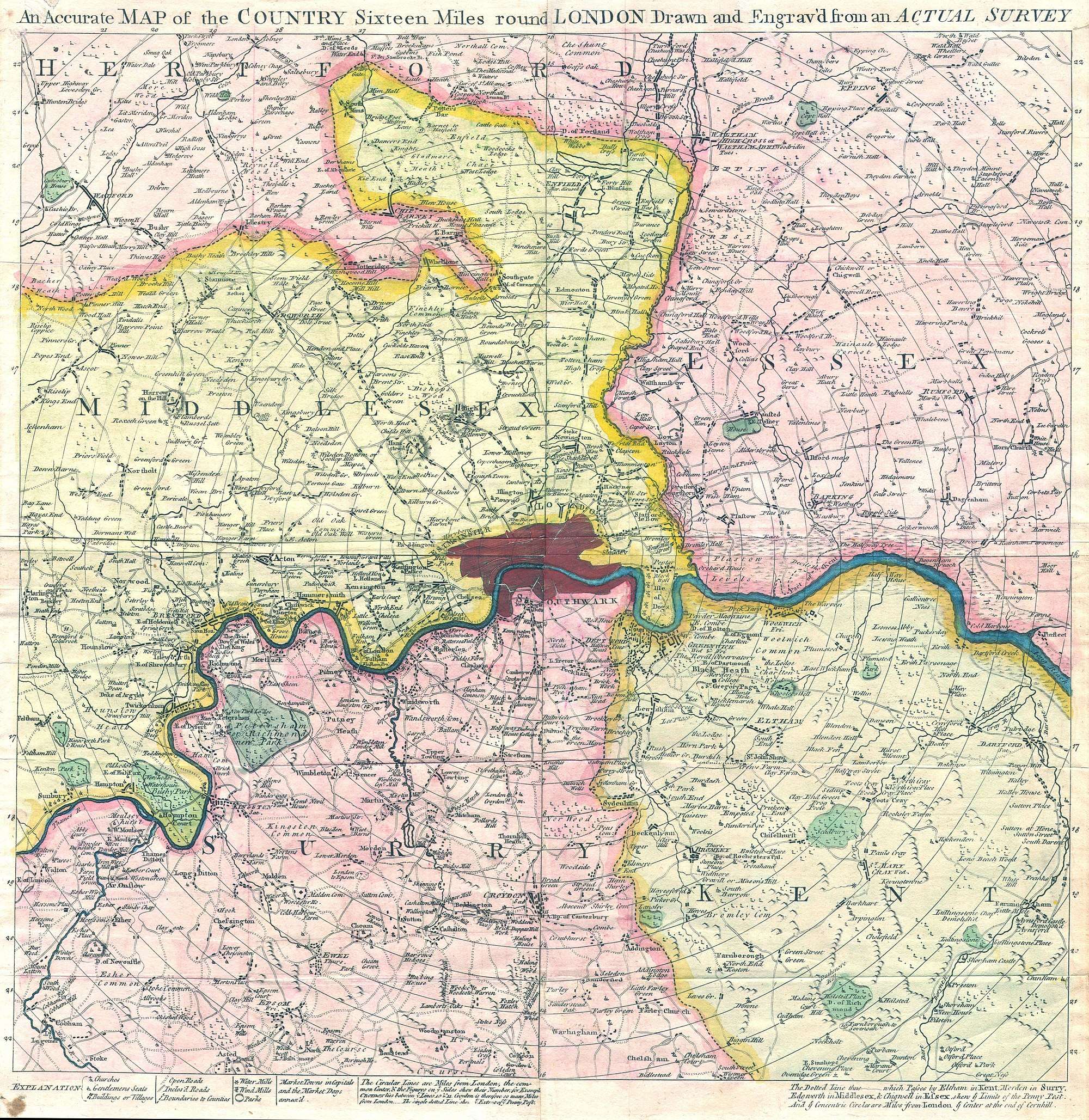

The title was first held by Odo, Count of Champagne created Earl of Holderness (an area of land occupying the far east of East Yorkshire along the North Sea and Humber Estuary) by his brother-in-law William the Conqueror after the Norman Conquest. Odo was stripped of his English lands after being implicated in a plot to put his own son Stephen of Aumale upon the throne of England in place of his first cousin, William II. However, the title was restored to Stephen in 1089.[1]

The first official creation, in 1621, along with the subsidiary title Baron Kingston upon Thames, of Kingston upon Thames in the County of Surrey, was in favour of John Ramsay, 1st Viscount of Haddington. As well as the Barony created with the Earldom, this Earl held the subsidiary titles Viscount of Haddington (1606), Lord Ramsay of Barns (1606) and Lord Ramsay of Melrose (1615), all in the Peerage of Scotland.[1]

The second creation, in 1644, was as a subsidiary title of the Dukedom of Cumberland conferred on Prince Rupert of the Rhine, a nephew of King Charles I.[1]

The third creation, in 1682, was in favour of Conyers Darcy, 2nd Baron Darcy and Conyers. In 1641, his father, Sir Conyers Darcy, had successfully petitioned King Charles I to be restored to the abeyant baronies of Darcy de Knayth (created 1332) and Conyers (created 1509), with remainder to his heirs male.[2] These were considered new creations that became extinct upon the death of the 4th Earl of Holderness, at which time the earldom also became extinct. (The 1641 decision was reversed in 1903, however, and both baronies were restored to the original remainders, which could be inherited by daughters.)[3]

Feudal Earl of Holderness (1071/72)

Earls of Holderness, 1st Creation (1621)

- John Ramsay, 1st Earl of Holderness (1580–1626)

Earls of Holderness, 2nd Creation (1644)

Barons Darcy and Conyers (1641)

- Conyers Darcy, 1st Baron Darcy and Conyers (d. 1654)

- Conyers Darcy, 2nd Baron Darcy and Conyers (created Earl of Holderness in 1682), see below.

Earls of Holderness, 3rd Creation (1682)

- Conyers Darcy, 1st Earl of Holderness (1599–1689)

- Conyers Darcy, 2nd Earl of Holderness (1620–1692)

- Robert Darcy, 3rd Earl of Holderness (1681–1722)

- Robert Darcy, 4th Earl of Holderness (1718–1778)

References

- Doyle, James William Edmund (1886). The Official Baronage of England: Showing the Succession, Dignities, and Offices of Every Peer from 1066 to 1885, with Sixteen Hundred Illustrations. Longmans, Green. pp. 201–293. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Collins, Arthur (1735). The Peerage of England: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the Peers of England. R. Gosling and T. Wotton. pp. 422–424. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knighthood (107 ed.). Burke's Peerage & Gentry. pp. 1028–1029. ISBN 0-9711966-2-1.

- A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3 pages 85-94: Heston and Isleworth: Introduction. ed. Susan Reynolds (London, 1962), republished at British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol3/pp85-94, accessed 14 October 2017.

- A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 3 pages 85-94: Heston and Isleworth: Introduction. ed. Susan Reynolds (London, 1962), republished at British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/middx/vol3/pp85-94, accessed 14 October 2017.