E.M.A.K.

E.M.A.K, or Elektronische Musik Aus: Köln (with "Köln" sometimes rendered as "Koeln" on album covers), was a German band and production collective based in Cologne in the 1980s. It produced experimental minimalist electronic dance and ambient pop music.

E.M.A.K | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Cologne, West Germany |

| Genres | Krautrock Electronic Ambient |

| Years active | 1981– |

| Labels | Originalton West |

| Website | http://www.originaltonwest.de/ |

| Members | Matthias Becker |

| Past members | Michael Filz Kurt Mill Michael Peschko Klaus Stühlen |

Members

The group was founded in 1981 in a small 8-track studio known as "Originalton West," run by Matthias Becker in the basement of the Cologne music store Hört-Hört. In January 1982 Becker released the first E.M.A.K. record, E.M.A.K. on the Originalton West record label.

Besides Becker, the members of E.M.A.K. included Michael Filz (who left after the release of E.M.A.K.), Kurt Mill (who left after the release of E.M.A.K. 2), Klaus Stühlen, and later Michael Peschko. In its initial form, E.M.A.K. was very much a collective of individuals, with Filz and Stühlen working on tracks alone, while Becker and Mill worked more collaboratively in the studio, and also acted as producers and final mixers on all E.M.A.K. tracks. Later, for the Vintage Synths releases, E.M.A.K. became a project led more firmly by Becker, with significant compositional help from Stühlen.[1]

Musical Style and Influences

E.M.A.K.’s influences include Kraftwerk, Neu!, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Neue Musik and musique concrète,[1] as well as Pink Floyd and the White Noise project associated with the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.[2] Much of E.M.A.K.'s musical style was directly formed from experimentation with various instruments. These included analogue synthesizers such as a Mini-Moog and a Synthanorma Sequencer (a German sequencer built by Hajo Wiechers of Matthen & Wiechers/ Bonn similar to the sequencer of the large Moog system), a Fender Rhodes piano (customized by Stühlen with external treatments such as distortion, echo chambers, and improvised effects), and a Roland TR-808 drum machine. E.M.AK. and E.M.A.K. 2 were released pre-sampler and pre-midi and so took a manual tape-based approach to looping and musique concrète parts. E.M.A.K. 3 used the AKAI S612 midi sampler and a Commodore 64.[1]

Although a critical part of the general history of German electronic music, E.M.A.K.’s location in Cologne during the 1980s meant they could pursue their own musical interests, relatively undisturbed by the demands of markets or fashions.[1] Becker felt that E.M.A.K. fell between generations, even when those generations worked in Cologne. E.M.A.K.'s music was influenced by older German electronic music, from that of Karlheinz Stockhausen to Can, both based in or near Cologne, but was also deliberately different, the band's name even cocking a deliberate snook at Stockhausen's self-appropriation of elektronische Musik.[2] The later E.M.A.K. project, Vintage Synths, would represent a further recasting of the history of electronic music, away from the focus on personalities such as Stockhausen and firmly onto the music machines themselves.[2] Becker also felt little connection with Neue Deutsche Welle bands such as Nena or D.A.F., although he admired the production work of the Cologne-based Conny Plank for some of these.[2]

E.M.A.K. were part of the club scene in Cologne,[2] and their own music often involved atmospheric extended pulsating rhythms. Only very rarely did E.M.A.K.’s music include vocals. The track “Filmmusik” from E.M.A.K. was a local club hit in Cologne,[1] although Becker himself preferred not to dance.[2]

Vintage Synthesizers

In 1987 Becker began writing a column for a German music magazine called “Synthesizer von Gestern”. This developed into the Vintage Synths project. Three Vintage Synths albums were released. These albums collected compositions for various specific synthesizers, each piece produced using only one particular synth. The albums were also accompanied by 2 books with historical and photographic studies of the various synthesizers.[1][3]

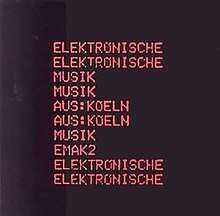

Album covers

The first three E.M.A.K. albums feature distinctively simple covers, which arrange the words of the group’s name in uppercase letters against a monochrome background to form the letter ‘E’. This was deliberate tribute to the early album covers of Neu! And Kraftwerk.[1]

The Originalton West label

Initially set up to release Becker’s and E.M.A.K.’s music, the Originalton West label also released music by other German electroacoustic and experimentalist musicians such as Oskar Sala, Claus Brüse, Camera Obscura (the German band), and Michael Peters, as well as Greek Rebetiko and African music.[1][3]

Discography

Albums

- E.M.A.K. (Originalton West, 1982)

- E.M.A.K. 2 (Originalton West, 1983)

- E.M.A.K. 3 (Originalton West, 1985)

- Vintage Synths Vol. 1 (Originalton West, 1990)

- Vintage Synths Vol. 2 (Originalton West, 1992)

- Vintage Synths Vol. 3 (Originalton West, 1994)

Singles

- "Sunken Galleons and Pirate Pictures" (1986)[4]

- "Tanz in den Himmel" (Soul Jazz Records, 2011)

Compilations

- Best of E.M.A.K.: Vol. 1-3 (Originalton West, 1994)

- A Synthetic History of E.M.A.K. 1982-88 (Soul Jazz Records, 2011)

References

- A Synthetic History of E.M.A.K. 1982-88 (Media notes). E.M.A.K. UK: Soul Jazz Records. 2011. p. 8.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Barry, Robert (23 December 2010). ""I Mostly Didn't Dance, But Stared At The Ceiling": An Interview With EMAK". The Quietus. TheQuietus.com. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Becker, Matthias. "Catalogue for Originalton West Records" (in German and English). Cologne, Germany: Originalton West Records.

- "Discogs entry for E.M.A.K."