Sciaenidae

Sciaenidae are a family of fish in the order Perciformes.[2][3] They are commonly called drums or croakers[2][3] in reference to the repetitive throbbing or drumming sounds they make.[4] The family consists of about 286[3] to 298 species[5] in about 66[3] to 70 genera.[2]

| Sciaenidae | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Atlantic croaker, Micropogonias undulatus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Perciformes |

| Superfamily: | Percoidea |

| Family: | Sciaenidae Cuvier, 1829[1] |

| Genera | |

|

About 66–70, see text | |

Characteristics

A sciaenid has a long dorsal fin reaching nearly to the tail, and a notch between the rays and spines of the dorsal, although the two parts are actually separate.[6] Drums are somberly coloured, usually in shades of brown, with a lateral line on each side that extends to the tip of the caudal fin. The anal fin usually has two spines, while the dorsal fins are deeply notched or separate. Most species have a rounded or pointed caudal fin. The mouth is set low and is usually inferior. Their croaking mechanism involves the beating of abdominal muscles against the swim bladder.[6]

Sciaenids are found worldwide, in both fresh and salt water, and are typically benthic carnivores, feeding on invertebrates and smaller fish. They are small to medium-sized, bottom-dwelling fishes living primarily in estuaries, bays, and muddy river banks. Most of these fish types avoid clear waters, such as coral reefs and oceanic islands, with a few notable exceptions (e.g. reef croaker, high-hat, and spotted drum). They live in warm-temperate and tropical waters and are best represented in major rivers in Southeast Asia, northeast South America, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Gulf of California.[6]

In the United States most fisherman consider freshwater drum to be rough fish not suitable for eating, similar to carp, gar, and buffalo fish, although there are a number of people that enjoy fishing for these species and eating them, despite their limitations.[7]

Fisheries

They are excellent food and sport fish, and are commonly caught by surf and pier fishers. Some are important commercial fishery species, notably small yellow croaker with reported landings of 218,000–407,000 tonnes in 2000–2009; according to FAO fishery statistics, it was the 25th most important fishery species worldwide.[8] However, a large proportion of the catch is not reported at species level; in the FAO fishery statistics, the category "Croakers, drums, not elsewhere included", is the largest one within sciaenids, with annual landings of 431,000–780,000 tonnes in 2000–2009, most of which were reported from the western Indian Ocean (FAO fishing area 51) and northwest Pacific (FAO fishing area 61).[8]

Croaking mechanism

A notable trait of sciaenids is the ability to produce a "croaking" sound. However the pitch and use of croaking varies species to species. The croaking ability is a distinguishing characteristic of sciaenids.[4] The croaking mechanism is used by males as a mating call in some species.

To produce the croaking sound, special muscles vibrate against the swim bladder.[9] These muscles are called sonic muscle fibres, and run horizontally along the fish's body on both sides around the swim bladder, connected to a central tendon that surrounds the swim bladder ventrally. These sonic muscle fibres are repeatedly contracted against the swim bladder to produce the croaking sound that gives drum and croaker their common name, effectively using the swim bladder as a resonating chamber. The sciaenids' large swim bladder is more expansive and branched than other species, which aids in the croaking.[10] In some species the sonic muscle fibres are only present in males. These muscles strengthen during the mating season and are allowed to atrophy the rest of the time, deactivating the croaking mechanism.[9] In other species, most notably the Atlantic croaker, the croaking mechanism is present in both sexes and remains active year-round. These species are thought to use croaking for communication, such as announcing hazards and location when in turbid water.[9]

Croaking in communication

In some species, croaking is used for communication aside from attracting mates. For those species that have year-round croaking ability, the croaks may serve as a low-aggression warning during group feeding, as well as to communicate location in cloudy water. In those species that lack the ability to croak year-round, croaking is usually restricted to males for attracting mates. A disadvantage to the croaking ability is that it allows bottlenose dolphin to easily locate large groups of croaker and drum as they broadcast their position, indicating large amounts of food for the dolphins.[9]

Genera

- Aplodinotus

- Argyrosomus

- Aspericorvina

- Atractoscion

- Atrobucca

- Austronibea

- Bahaba

- Bairdiella

- Boesemania

- Cheilotrema

- Chrysochir

- Cilus

- Collichthys

- Corvula

- Ctenosciaena

- Cynoscion

- Daysciaena

- Dendrophysa

- Elattarchus

- Equetus

- Genyonemus

- Isopisthus

- Jefitchia

- Johnius

- Kathala

- Larimichthys

- Larimus

- Leiostomus

- Lonchurus

- Macrodon

- Macrospinosa

- Megalonibea

- Menticirrhus

- Micropogonias

- Miichthys

- Miracorvina

- Nebris

- Nibea

- Odontoscion

- Ophioscion

- Otolithes

- Otolithoides

- Pachypops

- Pachyurus

- Panna

- Paralonchurus

- Paranebris

- Paranibea

- Pareques

- Pennahia

- Pentheroscion

- Petilipinnis

- Plagioscion

- Pogonias

- Protonibea

- Protosciaena

- Pseudotolithus

- Pteroscion

- Pterotolithus

- Robaloscion

- Roncador

- Sciaena

- Sciaenops

- Seriphus

- Sonorolux

- Stellifer

- Totoaba

- Umbrina

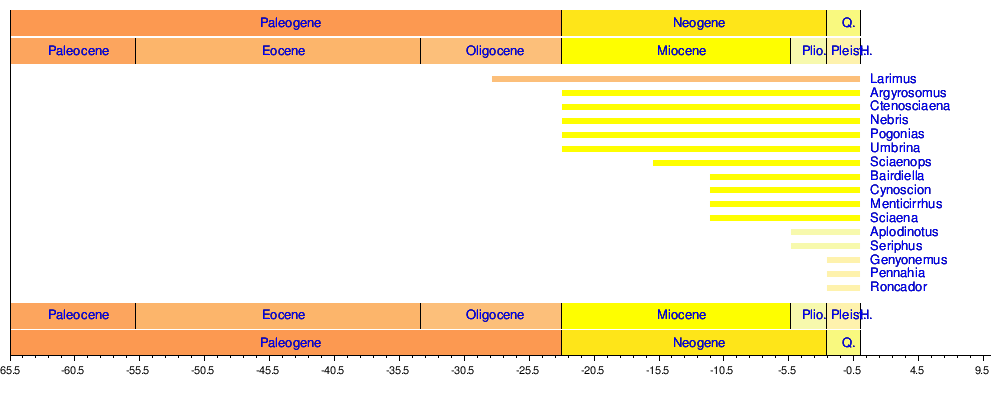

Timeline of genera

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sciaenidae. |

References

- Richard van der Laan; William N. Eschmeyer & Ronald Fricke (2014). "Family-group names of recent fishes". Zootaxa. 3882 (2): 1–230.

- Nelson, J. S. (2006). Fishes of the World (4 ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2019). "Sciaenidae" in FishBase. April 2019 version.

- Ramcharitar, John; Gannon, Damon; Popper, Arthur (May 16, 2006), "Bioacoustics of fishes of the family Sciaenidae", Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 135 (5): 1409–1431, doi:10.1577/T05-207.1

- Eschmeyer, W. N.; R. Fricke & R. van der Laan, eds. (5 August 2019). "Species by Family/Subfamily". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- Johnson, G.D. & Gill, A.C. (1998). Paxton, J.R. & Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- "Why These Overlooked Fish May Be the Tastiest (and Most Sustainable) - WSJ". Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) (2011). Yearbook of fishery and aquaculture statistics 2009. Capture production (PDF). Rome: FAO.

- Roach, John (November 7, 2005), Fish Croaks Like a Frog, But Why?, retrieved December 1, 2011

- Collin, Shaun; N. Justin Marshall (2003). Sensory processing in aquatic environments. New York: Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-0-387-95527-8.

Further reading

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 363: 1–560. Retrieved 2011-05-19.