Double hull

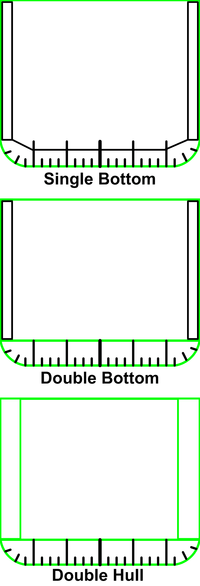

A double hull is a ship hull design and construction method where the bottom and sides of the ship have two complete layers of watertight hull surface: one outer layer forming the normal hull of the ship, and a second inner hull which is some distance inboard, typically by a few feet, which forms a redundant barrier to seawater in case the outer hull is damaged and leaks.

The space between the two hulls is sometimes used for storage of ballast water.

Double hulls are a more extensive safety measure than double bottoms, which have two hull layers only in the bottom of the ship but not the sides. In low-energy collisions, double hulls can prevent flooding beyond the penetrated compartment. In high-energy collisions, however, the distance to the inner hull is not sufficient and the inner compartment is penetrated as well.

Double hulls or double bottoms have been required in all passenger ships for decades as part of the Safety Of Life At Sea or SOLAS Convention.[1]

Oil tankers

Double hulls' ability to prevent or reduce oil spills led to double hulls being standardized for other types of ships including oil tankers by the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships or MARPOL Convention. A double hull does not protect against major, high-energy collisions or groundings which cause the majority of oil pollution, despite this being the reason that the double hull was mandated by United States legislation.[2] After the Exxon Valdez oil spill disaster, when that ship grounded on Bligh Reef outside the port of Valdez, Alaska, the US Government required all new oil tankers built for use between US ports to be equipped with a full double hull.

Submarines

In submarine hulls, the double hull structure is significantly different, consisting of an outer light hull and inner pressure hull, with the outer hull intended more to provide a hydrodynamic shape for the submarine than the cylindrical inner pressure hull. In addition to tailoring the flow of water around the submarine (also known as hydrodynamic bypass), this outer skin serves as a mounting point for anechoic tiles, which are designed specifically to absorb sound rather than reflect it, helping to hide the vessel from sonar detection.

References

- "Chapter II-1: Construction - Structure, subdivision and stability, machinery and electrical installations, Regulation 12: Double bottoms in passenger ships", International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) (PDF), International Maritime Organization (IMO), 2004 [1974], p. 51, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2012, retrieved 17 July 2012

- Jack Devanney (2006): The Tankship Tromedy, The Impending Disasters in Tankers, CTX Press, Tavernier, Florida, ISBN 0-9776479-0-0