Insulated glazing

Insulating glass (IG), such consists of two or more glass window panes separated by a vacuum or gas-filled space to reduce heat transfer across a part of the building envelope.[1][2] A window with insulating glass is commonly known as double glazing or a double-paned window, triple glazing or a triple-paned window, or quadruple glazing or a quadruple-paned window, depending upon how many panes of glass are used in its construction.

Insulating glass units (IGUs) are manufactured with glass in range of thickness from 3 to 10 mm (1/8" to 3/8") or more in special applications. Laminated or tempered glass may also be used as part of the construction. Most units are produced with the same thickness of glass used on both panes but special applications such as acoustic attenuation or security may require wide ranges of thicknesses to be incorporated in the same unit.

Double-hung and storm windows

Insulating glass is an evolution from older technologies known as double-hung windows and storm windows. Traditional double-hung windows used a single pane of glass to separate the interior and exterior spaces.

- In the summer, a window screen would be installed on the exterior over the double-hung window to keep out animals and insects.

- In the winter, the screen was removed and replaced with a storm window, which created a two-layer separation between the interior and exterior spaces, increasing window insulation in cold winter months. To permit ventilation the storm window may be hung from removable hinge loops and swung open using folding metal arms. No screening was usually possible with open storm windows, though in the winter, insects typically are not active.

Traditional storm windows and screens are relatively time consuming and labor-intensive, requiring removal and storage of the storm windows in the spring, and reinstallation in the fall and storage of the screens. The weight of the large storm window frame and glass makes replacement on upper-stories of tall buildings a difficult task requiring repeatedly climbing a ladder with each window and trying to hold the window in place while securing retaining clips around the edges. However, current reproductions of these old-style storm windows can be made with detachable glass in the bottom pane that can be replaced with a detachable screen when desired. This eliminates the need for changing the entire storm window according to the seasons.

Insulated glazing forms a very compact multi-layer sandwich of air and glass, which eliminates the need for storm windows. Screens may also be left installed year-round with insulated glazing, and can be installed in a manner that permits installation and removal from inside the building, eliminating the requirement to climb up the exterior of the house to service the windows. It is possible to retrofit insulated glazing into traditional double-hung frames, though this would require significant modification to the wood framed due to the increased thickness of the IG assembly.

Modern window units with IG typically completely replace the older double-hung unit, and include other improvements such as better sealing between the upper and lower windows, and spring-operated weight balancing that removes the need for large hanging weights inside the wall next to the windows, allowing for more insulation around the window and reducing air leakage, provides robust protection against the sun and will keep the house cool in the hot summer and warm in winter. These spring-operated balancing mechanisms also typically permit the top of the windows to swing inward, permitting cleaning of the exterior of the IG window from inside the building.

Spacer

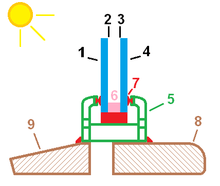

The glass panes are separated by a "spacer". A spacer, which may be of the warm edge type, is the piece that separates the two panes of glass in an insulating glass system, and seals the gas space between them. The first spacers were made primarily of steel and aluminum, which manufacturers thought provided more durability, and their lower price means that they remain common.

However, metal spacers conduct heat (unless the metal is thermally improved), undermining the ability of the insulated glass unit (IGU) to reduce heat flow. It may also result in water or ice forming at the bottom of the sealed unit because of the sharp temperature difference between the window and surrounding air. To reduce heat transfer through the spacer and increase overall thermal performance, manufacturers may make the spacer out of a less-conductive material such as structural foam. A spacer made of aluminum that also contains a highly structural thermal barrier reduces condensation on the glass surface and improves insulation, as measured by the overall U-value.

- A spacer that reduces heat flow in glazing configurations may also have characteristics for sound dampening where external noise is an issue.

- Typically, spacers are filled with or contain desiccant to remove moisture trapped in the gas space during manufacturing, thereby lowering the dew point of the gas in that space, and preventing condensation from forming on surface #2 when the outside glass pane temperature falls.

- New technology has emerged to combat the heat loss from traditional spacer bars, including improvements to the structural performance and long-term-durability of improved metal (aluminum with a thermal barrier) and foam spacers.

Construction

IGUs are often manufactured on a made to order basis on factory production lines, but standard units are also available. The width and height dimensions, the thickness of the glass panes and the type of glass for each pane as well as the overall thickness of the unit must be supplied to the manufacturer. On the assembly line, spacers of specific thicknesses are cut and assembled into the required overall width and height dimensions and filled with desiccant. On a parallel line, glass panes are cut to size and washed to be optically clear.

.svg.png)

An adhesive sealant (polyisobutylene) is applied to the face of the spacer on each side and the panes pressed against the spacer. If the unit is gas-filled, two holes are drilled into the spacer of the assembled unit, lines are attached to draw out the air out of the space and replacing it (or leaving just vacuum) with the desired gas. The lines are then removed and holes sealed to contain the gas. The more modern technique is to use an online gas filler, which eliminates the need to drill holes in the spacer. The units are then sealed on the edge side using either polysulfide or silicone sealant or similar material to prevent humid outside air from entering the unit. The desiccant will remove traces of humidity from the air space so that no water appears on the inside faces (no condensation) of the glass panes facing the air space during cold weather. Some manufacturers have developed specific processes that combine the spacer and desiccant into a single step application system.

The insulating glazing unit, consisting of two glass panes bound together into a single unit with a seal between the edges of the panes, was patented in the United States by Thomas Stetson in 1865.[3] It was developed into a commercial product in the 1930s, when several patents were filed, and a product was announced by the Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company in 1944.[4] Their product was sold under the Thermopane brand name, which had been registered as a trademark in 1941. The Thermopane technology differs significantly from contemporary IGUs. The two panes of glass were welded together by a glass seal, and the two panes were separated by less than the 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) typical of modern units.[5] The brand name Thermopane has entered the vocabulary of the glazing industry as the genericized trademark for any IGU.

Thermal performance

The maximum insulating efficiency of a standard IGU is determined by the thickness of the space. Typically, most sealed units achieve maximum insulating values using a space of 16–19 mm (0.63–0.75 in) when measured at the centre of the IGU.

IGU thickness is a compromise between maximizing insulating value and the ability of the framing system used to carry the unit. Some residential and most commercial glazing systems can accommodate the ideal thickness of a double-paned unit. Issues arise with the use of triple glazing to further reduce heat loss in an IGU. The combination of thickness and weight results in units that are too unwieldy for most residential or commercial glazing systems, particularly if these panes are contained in moving frames or sashes.

This trade-off does not apply to vacuum insulated glass (VIG), or evacuated glazing,[6] as heat loss due to convection is eliminated, leaving radiation losses and conduction through the edge seal and required supporting pillars over the face area.[7][8] These VIG units have most of the air removed from the space between the panes, leaving a nearly-complete vacuum. VIG units which are currently on the market are hermetically sealed along their perimeter with solder glass, that is, a glass frit (powdered glass) having a reduced melting point is heated to join the components. This creates a glass seal that experiences increasing stress with increasing temperature differential across the unit. This stress may limit the maximum allowable temperature differential. One manufacturer provides a recommendation of 35 °C. Closely spaced pillars are required to reinforce the glazing to resist the pressure of the atmosphere. Pillar spacing and diameter limited the insulation achieved by designs available beginning in the 1990s to R = 4.7 h·°F·ft2/BTU (0.83 m2·K/W) no better than high quality double glazed insulated glass units. Recent products claim performance of R = 14 h·°F·ft2/BTU (2.5 m2·K/W) which exceeds triple glazed insulated glass units.[8] The required internal pillars exclude applications where an unobstructed view through the glazing unit is desired, i.e. most residential and commercial windows, and refrigerated food display cases.

Vacuum technology is also used in some non-transparent insulation products called vacuum insulated panels.

An older-established way to improve insulation performance is to replace air in the space with a lower thermal conductivity gas. Gas convective heat transfer is a function of viscosity and specific heat. Monatomic gases such as argon, krypton and xenon are often used since (at normal temperatures) they do not carry heat in rotational modes, resulting in a lower heat capacity than poly-atomic gases. Argon has a thermal conductivity 67% that of air, krypton has about half the conductivity of argon.[9] Argon is almost 1% of the atmosphere and isolated at a moderate cost. Krypton and xenon are only trace components of the atmosphere and very expensive. All of these "noble" gases are non-toxic, clear, odorless, chemically inert, and commercially available because of their widespread application in industry. Some manufacturers also offer sulfur hexafluoride as an insulating gas, especially to insulate sound. It has only 2/3 the conductivity of argon, but it is stable, inexpensive and dense. However, sulfur hexafluoride is an extremely potent greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. In Europe, SF

6 falls under the F-Gas directive which ban or control its usage for several applications. Since 1 January 2006, SF

6 is banned as a tracer gas and in all applications except high-voltage switchgear.[10]

In general, the more effective a fill gas is at its optimum thickness, the thinner the optimum thickness is. For example, the optimum thickness for krypton is lower than for argon, and lower for argon than for air.[11] However, since it is difficult to determine whether the gas in an IGU has become mixed with air at time of manufacture (or becomes mixed with air once installed), many designers prefer to use thicker gaps than would be optimum for the fill gas if it were pure. Argon is commonly used in insulated glazing as it is the most affordable. Krypton, which is considerably more expensive, is not generally used except to produce very thin double glazing units or extremely high performance triple-glazed units. Xenon has found very little application in IGUs because of cost.[12]

Heat insulating properties

The effectiveness of insulated glass can be expressed as an R-value. The higher the R-value, the greater is its resistance to heat transfer. A standard IGU consisting of clear uncoated panes of glass (or lights) with air in the cavity between the lights typically has an R-value of 0.35 K·m2/W.

Using US customary units, a rule of thumb in standard IGU construction is that each change in the component of the IGU results in an increase of 1 R-value to the efficiency of the unit. Adding argon gas increases the efficiency to about R-3. Using low emissivity glass on surface #2 will add another R-value. Properly designed triple-glazed IGUs with low emissivity coatings on surfaces #2 and #4 and filled with argon gas in the cavities result in IG units with R-values as high as R-5. Certain vacuum insulated glass units (VIGU) or multi-chambered IG units using coated plastic films result in R-values as high as R-12.5

Additional layers of glazing provide the opportunity for improved insulation. While the standard double glazing is most widely used, triple glazing is not uncommon, and quadruple glazing is produced for very cold environments such as Alaska.[13][14] Even quintuple and six-pane glazing (four or five cavities) is available - with mid-pane insulation factors equivalent to walls.[15][16][17]

Acoustic insulating properties

In some situations the insulation is in reference to noise mitigation. In these circumstances a large air space improves the noise insulation quality or sound transmission class. Asymmetric double glazing, using different thicknesses of glass rather than the conventional symmetrical systems (equal glass thicknesses used for both lights) will improve the acoustic attenuation properties of the IGU. If standard air spaces are used, sulfur hexafluoride can be used to replace or augment an inert gas[18] and improve acoustical attenuation performance.

Other glazing material variations affect acoustics. The most widely used glazing configurations for sound dampening include laminated glass with varied thickness of the interlayer and thickness of the glass. Including a structural, thermally improved aluminum thermal barrier air spacer in the insulating glass can improve acoustical performance by reducing the transmission of exterior noise sources in the fenestration system.

Reviewing the glazing system components, including the air space material used in the insulating glass, can ensure overall sound transmission improvement.

Longevity

The life of an IGU varies depending on the quality of materials used, size of gap between inner and outer pane, temperature differences, workmanship and location of installation both in terms of facing direction and geographic location, as well as the treatment the unit receives. IG units typically last from 10 to 25 years, with windows facing the equator often lasting less than 12 years. IGUs typically carry a warranty for 10 to 20 years depending upon the manufacturer. If IGUs are altered (such as installation of a solar control film) the warranty may be voided by the manufacturer.

The Insulating Glass Manufacturers Alliance (IGMA)[19] undertook an extensive study to characterize the failures of commercial insulating glass units over a 25-year period.

For a standard construction IG unit, condensation collects between the layers of glass when the perimeter seal has failed and when the desiccant has become saturated, and can generally only be eliminated by replacing the IGU. Seal failure and subsequent replacement results in a significant factor in the overall cost of owning IGUs.

Large temperature differences between the inner and outer panes stress the spacer adhesives, which can eventually fail. Units with a small gap between the panes are more prone to failure because of the increased stress.

Atmospheric pressure changes combined with wet weather can, in rare cases, eventually lead to the gap filling with water.

The flexible sealing surfaces preventing infiltration around the window unit can also degrade or be torn or damaged. Replacement of these seals can be difficult to impossible, due to IG windows commonly using extruded channel frames without seal retention screws or plates. Instead, the edge seals are installed by pushing an arrow-shaped indented one-way flexible lip into a slot on the extruded channel, and often cannot be easily extracted from the extruded slot to be replaced.

In Canada, since the beginning of 1990, there are some companies offering servicing of failed IG units. They provide open ventilation to the atmosphere by drilling hole(s) in the glass and/or spacer. This solution often reverses the visible condensation, but cannot clean the interior surface of the glass and staining that may have occurred after long-term exposure to moisture. They may offer a warranty from 5 to 20 years. This solution lowers the insulating value of the window, but it can be a "green" solution when the window is still in good condition. If the IG unit had a gas fill (e.g. argon or krypton or a mixture) the gas is naturally dissipated and the R-value suffers.

Since 2004, there are also some companies offering the same restoration process for failed double-glazed units in the UK, and there is one company offering restoration of failed IG units in Ireland since 2010.

Thermal stress cracking

Thermal stress cracking isn't different for insulated glazing and uninsulated glazing. Temperature differences across the surface of glass panes can lead to cracking of the glass. This typically occurs where the glass is partially shaded and one section is heated in sunlight. Tinted glass increases heating and thermal stress, while annealing reduces internal stress built into the glass during manufacturing leaving more strength available to resist thermal cracking. [20]

Thermal expansion creates internal pressure, or stress, where expanding warm material is retrained by cooler material. A crack may form if the stress exceeds the material strength and the crack will propagate until the stress at the tip of the crack is below the material's strength. Typically cracks initiate and propagate from the narrow shaded cut edge where the material is weak and the stress is spread over a small glass volume compared to the open area. Glass thickness has no direct effect on thermal cracking in windows because both thermal stress and material strength are proportional to thickness. While thicker glass will have more strength remaining after supporting wind loads, that's usually only a significant factor for large glazing units on tall buildings and wind improves heat dissipation. Increased resistance to cracking with thicker glazing in common residential and commercial applications is more reliably result of using tempered glass to satisfy building safety codes requiring its use to reduce the severity of injuries when broken. Cut edge stresses have to be reduced by annealing prior to tempering and that removes stress concentrations created during glass cutting and that significantly increases the stress required to initiate a crack from the edge. The cost to process tempered glass is much greater than the cost difference between 1/8" (3 mm) glass and 3/16" (5 mm) or 1/4" (6.5 mm) material, prompting glaziers to suggest replacing cracked glazing with thicker glass. It may also avoid revealing to the customer that tempered glass should have been used initially.

Estimating heat loss from double-glazed windows

Given the thermal properties of the sash, frame, and sill, and the dimensions of the glazing and thermal properties of the glass, the heat transfer rate for a given window and set of conditions can be calculated. This can be calculated in kW (kilowatts), but more usefully for cost benefit calculations can be stated as kWh pa (kilowatt hours per annum), based on the typical conditions over a year for a given location.

The glass panels in double-glazed windows transmit heat in both directions by radiation, through the glazing by conduction and across the gap between the panes by convection, by conduction through the frame, and by infiltration around the perimeter seals and the frame's seal to the building. The actual rates will vary with the conditions throughout the year, and while solar gain may be much welcomed in the winter (depending on local climate), it may result in increased air conditioning costs in the summer. Unwanted heat transfer can be mitigated by for example using curtains at night in the winter and using sun shades during the day in the summer. In an attempt to provide a useful comparison between alternative window constructions the British Fenestration Rating Council have defined a "Window Energy Rating" WER, ranging from A for the best down through B and C etc. This takes into account a combination of the heat loss through the window (U value, the reciprocal of R-value), the solar gain (g value), and loss through air leakage around the frame (L value). For example, an A Rated window will in a typical year gain as much heat from solar gain as it loses in other ways (however the majority of this gain will occur during the summer months, when the heat may not be needed by the building occupant). This provides better thermal performance than a typical wall.[21]

See also

- Curtain wall

- Quadruple glazing

- Passive solar design

- Window

References

- "Vacuum Insulating Glass – Past, Present and Prognosis".

- https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/9/6/936/pdf

- US patent 49167, Stetson, Thomas D., "Improvement in Window Glass", issued 1865-08-12

- Jester, Thomas C., ed. (2014). Twentieth-Century Building Materials: History and Conservation. Getty Publications. p. 273. ISBN 9781606063255. See note 25.

- Wilson, Alex (22 March 2012). "The Revolution in Window Performance — Part 1". Green Building Advisor.

- Norton, Brian (2013). Harnessing Solar Heat. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-7275-5.

- "Development and quality control of vacuum glazing by N. Ng and L. So; University of Sydney". Glassfiles.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "Vacuum Insulated Glazing (VIG)". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. U.S. Department of Energy. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Kaye and Laby. Thermal conductivities of gases". Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "F-gas and SF6 restrictions". euractiv.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ASHRAE Handbook, Volume 1, Fundamentals, 1993

- http://www.ktu.lt/ultra/journal/pdf_51_2/51-2004-Vol.2_01-J.Butkus.pdf

- Corporation, Bonnier (1 February 1980). "Popular Science". Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved 23 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Quadruple-Glazed House Uses Geothermal Pump to Maintain a Constant Temperature". inhabitat.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "Green Products". buildinggreen.com. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- "'Superwindows' To the Rescue?". GreenBuildingAdvisor.com. 7 June 2011. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- Kralj, Aleš; Drev, Marija; Žnidaršič, Matjaž; Černe, Boštjan; Hafner, Jože; Jelle, Bjørn Petter (May 2019). "Investigations of 6-pane glazing: Properties and possibilities". Energy and Buildings. 190: 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.02.033.

- Hopkins, Carl (2007). Sound insulation - Google Books. ISBN 9780750665261. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- "IGMA". Igmaonline.org. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Viracon Corporation, Owatonna, MN, "Tech Talk: Thermal stress cracking", 2001, http://www.viracon.com/images/pdf/TTThermalStress.pdf

- Pierce, Connie C. "energy and acoustic solutions". THERMOTEK. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- Handbook of Chemistry & Physics, 62ed, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-0462-8

External links

- Architectural Windows & Doors Australia

- Graham Machin Windows & Doors Staffordshire